Case Study: The Dynamics of Mumbai South

Will the digital efforts of the candidates bring an indifferent electorate to the poll booths this time?

The Mumbai South constituency is a microcosm of the ‘many Indias’ trope.

You’ll find members of every religion and community here. Within touching distance of each other, you’ll see immense wealth—some of India’s richest live here—and grinding poverty gleaming high-rises and posh bungalows, and crumbling chawls and slums where the narrow alleys double as gutters malls overflowing with brands you’d spot on the high streets of the world’s capitals loom over illegal street vendors with antennae always alert for municipality vans coming to confiscate their merchandise, carts and livelihoods.

The poor, as with the poor everywhere, can be counted on to come out and vote. Elections are the only chance most have to make their voices heard. The more affluent, though, hardly stir out of their towers on E-Day: Mumbai South has some of the poorest voter turnouts in the country.So it is particularly interesting to look at the battle for this seat, and how the main candidates are using technology to gain an edge. And, within that, whether their efforts will persuade the smartphone-flaunting, internet-savvy affluent to overcome their lethargy and get to the polling booths.

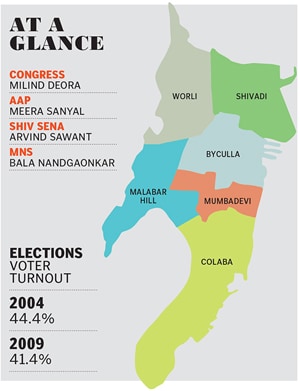

First, though, a look at the major contenders.

Milind Deora, the sitting MP seeking his third term in Parliament, is the scion of a political family. His father, Murli Deora, was once mayor of Mumbai, won the same Lok Sabha seat four times he is a Rajya Sabha MP and a former Union minister. The younger Deora is a minister too (Minister of State for Information Technology and Communications, and shipping).

The Shiv Sena has put up Arvind Sawant. He is a charismatic trade union leader of long standing (he heads MTNL’s employee union), deputy leader of the party, and a two-time MLC. He is said to be very close to Sena chief Uddhav Thackeray—son of the party’s late founder Bal Thackeray—and Aditya Thackeray, Uddhav’s son and rising powerhouse in the party.

Meera Sanyal gave up corporate life, stood as an independent candidate for the Mumbai South seat in 2009, and won a measly 10,000-odd votes. This time, she has thrown her lot in with the Aam Aadmi Party (AAP), campaigning for it in the Delhi Assembly elections, and now standing as its candidate for Mumbai South.

Bala Nandgaonkar, of the Maharashtra Navnirman Sena (MNS), is a four-time MLA from Shivadi, or Sewri—one of the six state Assembly constituencies that make up the parliamentary constituency—having won the seat three times as a Sena candidate, and then, when he joined Raj Thackeray’s breakaway from the Shiv Sena, from the MNS. In the 2009 parliamentary election, he came second to Deora, just ahead of the Sena candidate, Mohan Rawale. However, Nandgaonkar and his party’s technology lead both did not respond to interview requests.

Deora, whose office was prompt in arranging a meeting, says he has been using technology for the last five years, to engage with his constituency through emails: “I was the first politician in the country to create a system of sending out a quarterly and a fortnightly newsletter. I’m on Twitter for the last few years, and I use that to keep people informed of my work. The number of people I see from different sections of society who are on different social media platforms… It’s fair to say that it’s not an elitist medium in South Mumbai at least.”

But how big is his mailing list? It has been built gradually, he says, with people sending in phone numbers and email addresses after events. “It’s not a huge database, unfortunately, but even if it’s just 40,000 people receiving the updates, it’s better than nobody knowing what I’m doing.”

And what about listening, research? “I use [social media] the other way around as well. I try and engage on Twitter sometimes, and I redirect a lot of messages and grievances to the concerned people. I don’t want it to be a monologue I’ve always wanted a dialogue.” Ultimately, he says, these platforms are “just other Jan Sampark Karyalays, public contact offices”.

As for data collection and analysis, “We’ve had some software providers coming to us with, for instance, booth-wise data. But it’s more my party that does that they use that data to direct work in that area. But we’re not buying data, sourcing data from third parties. I’m very careful about not spamming anyone,” he says. “I don’t know if we’re using it in a structured way we’re using it in an informal way. Take Twitter. It’s a brutally honest medium. I use it as a reality check. It gives me a good sense of what my constituents think, want and perceive.”

We mention the fears of increasing government and private surveillance and falling privacy levels, areas that he, as a minister, has a say in. He takes it straight on, telling us that the government takes it seriously, and that a privacy law is in the drafting stage. It would take time to become reality, and it would be up to the new government to make it happen. “Hopefully, if it’s my government… We were very keen to push it through.”

The Shiv Sena’s South Mumbai candidate is disarmingly frank about his own command over technology: “I am not very savvy you could say I’m a novice,” Arvind Sawant says, inviting you to chuckle with him at his own lack of skills.

But he is assisted by a team of tech-savvy volunteers, including his son, who, between them, bring in an impressive skill set and the burning loyalty characteristic of the Shivsainiks, as they call themselves. And, as his remarks later showed, he has a very sharp knowledge of the wide disparities amidst the people he hopes to represent, their needs and aspirations, the media they consume, and how to reach them.

The conversation strays to his analysis of the current political climate, and an enthusiastic and unflattering dissection of the powers that be. It takes time to bring him back to what we had met to discuss.

Make no mistake, though: He fully gets that technology is important, that he needs to be on social media, making sure he is quotable, that he delivers statements that his supporters can take viral. For, as he says, his biggest asset is that his party has large numbers of dedicated workers. With their door-to-door canvassing, guided by a software programme his team has got developed that gives them very granular data—as deep as individual buildings, not just the booth-wise EC data that are publicly available—he is confident that he will be able to reach out to all his potential voters: From the neglected poor, who, he says, are the ones he instinctively wants to reach out to, to the disinterested ‘elite’ who he understands that he must also appeal to.

In a slushy corner of Mumbai South, Meera Sanyal gets out of her car. AAP volunteers brief her on the route of the walk she is to take. Placards and leaflets are handed out from the back of a goods van, one of the team raises a microphone, and the amplifier he is carrying calls out to the world, telling all who will hear that Meera Sanyal is here, that she is from the AAP, and she is seeking their blessings.

These padyatras are a core part of her strategy, she says, on her way to one of them. “I learned in 2009 that face-to-face is very, very important: People want to see who you are and what you stand for. South Bombay is unique in that it is very dense and very vertical. So you can actually cover the entire constituency on foot.”

She is not in the least disheartened by the low number of votes she polled in 2009. “A lot of what I’m doing now is based on my learnings from 2009, and from the whole Obama campaign 1 and campaign 2, the standard-bearer for elections all over the world.”One thing she says she missed out on in 2009, was the “massive tsunami” of volunteers offering help, because her team then was too small to respond to all the emails and messages she got. “Clearly a repository for this needs to be a website,” she says. She found a platform, NationBuilder, designed for political campaigns, NGOs and small businesses, and decided to host her site there. The volunteering offers, communication, social media, are captured there, she says. And, she admits, “Despite spending a few months on it, I think we’re still using just a fraction of its capabilities.” Learning from the past again, she had an ethical hacker attempt to break the site, and she’s confident that it will last the course.

Facebook, Twitter, LinkedIn, she says, have come a long way since 2009. And she has been present on all the platforms, “to see how these mediums react, what they react to”. She gets that each one is different, that people use them in different ways, and that she must have an authentic voice in all of them. To cover all these ‘constituencies’ she uses HootSuite, which lets you post on multiple platforms, schedule posts, use many languages, and so on, and gauge the varied responses. Now, in the thick of the campaign, her team has taken over much of the response work. Another learning was that images have more impact than text, a result of the many-devices-in-one smartphone. She’s used photographs, “a visual campaign diary”, to counter the ‘Malabar Hill Memsaab’ tag her critics throw at her. The visuals are far more powerful, she says, than any verbal response could have been.

Her team is also documenting and studying everything they do, because “this is not the last election I’m going to fight!”

It is pertinent to note that if the MNS and Sena share of the 2009 vote were combined—which assumes the ‘Marathi Manoos’, which both lay strong claim to, would have voted as a community—Milind Deora would have been out of Parliament. Who played spoiler to whom is still up for debate!

In 2014, the Sena laid claim to the seat early, despite its national partner in the NDA, the BJP, making rumblings about putting a candidate there. And, once more, the MNS has thrown its hat in this will again, if conventional wisdom holds, split the Marathi vote. But Sanyal’s entry, the voice on the street says, evens things up a bit: She, they say, will split the ‘secular’ vote, eating into Congress’ share. This evens the field between the ‘leading’ candidates, Deora and Sawant.

The only certainty is this: If the reluctant ‘SoBo’ citizens get their rears off their armchairs and into the polling booths, technology would have wound up winning.

First Published: Apr 16, 2014, 06:19

Subscribe Now