Francisco D'Souza: Balancing Cognizant's Present and Future

Francisco D'Souza knew he had to peer into the future to keep Cognizant relevant. And he had to do this without taking his eyes off the present

Award: Best CEO Multinational

Francisco D’Souza

CEO, Cognizant Technology Solutions

Age: 45

Interests outside of work: A gadget freak, believer in Maker movement and likes to spend time with his children.

Why he won this award: For refocusing Cognizant after the 2008 shock so as to deliver superior growth based on customer-orientation. Married short-term aggressive performance without sacrificing investment for long-term growth.

Francisco D’Souza, the 45-year-old CEO of Cognizant Technology Solutions, should have a persistent headache. Pain, after all, does afflict those who are forced to look at the world through two different kinds of lenses: Telescopic for one eye and microscopic for the other. “A telescope to consider opportunities far into the future, and a microscope to scrutinise the challenges of the moment with intense magnification,” is how McKinsey’s global managing director Dominic Barton once put it.

There is no escaping this duality if you are in the IT sector today you don’t have a choice but to consider both the short term and the long term. The crisis is interesting, two-pronged. On the one hand, there is a slowdown. The momentum that helped the Indian IT services industry grow from a few million dollars to $100 billion (from exports and domestic sales), bestowing its top executives with superstar status, is lost there is a struggle to generate revenues. On the other hand, it is facing the kind of disruption that occurs only once in a decade or so. In 2000, it was the internet. Now, it is social media, mobile, analytics and cloud computing. Together these technologies are changing the way businesses are run and, in order to retain relevance, IT services companies have to evolve.

This change is risky. There are examples of companies that took the new technologies too seriously and got burnt. Consider Infosys. Many of its problems over the last few years can be traced to its ‘Infosys 3.0’ strategy, with its focus on products and platforms, and with its ambition to create tomorrow’s enterprise. The leadership was so enamoured with that vision that they dropped the ball on the cash cow—application development and maintenance. NR Narayana Murthy was compelled to come back from quasi-retirement, and one of the first things he did was to acknowledge this lost focus.

Cognizant did a rejig too, dividing its business into cash cow, immediate future and long-term future, calling these horizon one (H1), two (H2) and three (H3), respectively. D’Souza took charge of H3.

But this reorganisation was immediately followed by a shocker. In 2012, Cognizant had to revise its guidance downwards. The stock market was stunned: Here was a company that always outran its own guidance: It grew by 33 percent against the guidance of 26 percent in 2011, and 40 percent against 20 percent in 2010. Consequently, Cognizant lost 15 percent of its market cap when Nasdaq opened the next morning (May 18, 2012). The big questions followed: H3 is alright but what is the point in spending time booking a ticket from B to C when that very act will make you miss the train that takes you from A to B? Shouldn’t Cognizant get its act right in H1 and H2 before it thinks of H3? Or, in other words, wouldn’t it make sense for Cognizant to put the telescope aside and just look through the microscope?

For answers, D’Souza did not have to look too far into history.

A Crisis Without A Playbook

When the financial crisis struck the US in 2008, D’Souza was still a fresher in many ways. Not yet 40, he had just taken over as CEO. But it was apparent to him that the turbulence was going to impact Cognizant to an unprecedented extent. For one, most of Cognizant’s revenues came from the US, and over half of those from banking and financial services, the sector most affected. “None of us had seen, or been in, anything of that magnitude. There was no playbook,” he says.

His plan: Going back to the basics, which meant Cognizant’s senior management would spend more time with the customers and “look at the world through the customers’ point of view and not through our own”. When the crisis was at its peak, top managers were busy shuttling between customer offices across the world. Every other week, they would converge in Frankfurt where they refined their understanding of the crisis through discussion and debate.

They had found that companies, expectedly, wanted to cut costs but, at the same time, they were also willing to invest if it helped them ‘variablise’ their costs (ie, keep the costs in proportion to the volume of business through outsourcing, using contract workers, etc). That was because there was no clarity on how long the crisis would last and the direction the economy would take. They were seeking ways to ramp up or down depending on how the tide turns. For Cognizant, that showed a clear path. D’Souza and his team quickly developed a theme that would guide them and their clients through the crisis, shining through the fog, if you will.

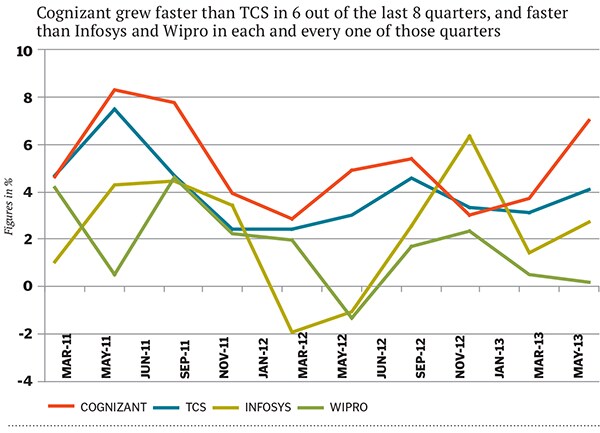

On the ground, this meant making more investments in areas such as business process management and remote infrastructure management. Cognizant scaled up its own delivery centres and hired more people. It also expanded its consulting services, hiring from big firms hit by the crisis. In the end, 2010 turned out to be one of the best years for Cognizant. It grew faster than its peers. And it was breathing down Infosys’s neck, the second-largest IT exporter in the country, founded several years before Cognizant came into existence.

This would have made any CEO happy. But, not D’Souza. “For him, it doesn’t matter how far you have come from where you started. What matters is where you are compared to where you could have been,” says Mahesh Venkateswaran, a senior vice president and a Cognizant veteran who has worked with D’Souza for over 16 years. In fact, as the year ended, D’Souza was disappointed that he had not been even more aggressive, invested more or made even more acquisitions.

In 2012, when he looked back at that phase for inspiration, it was clear to D’Souza that dropping the ball on the future was not an answer. He had to do both: Continue to invest in areas that would give Cognizant future growth without taking eyes off the present.

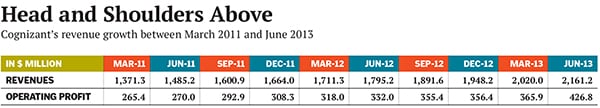

As 2013 nears its end, D’Souza seems to have achieved that balance. Cognizant overtook Infosys around this time last year, and the gap between the two has grown ever since. From a downward revision in 2012, it upped its guidance in 2013. It had one of its best quarters recently, and is ahead of its peers on many measures (see ‘Head and Shoulders Above’).

As for H3, that has brought in half a billion dollars in revenues, and might touch a billion in the not too distant future. As for D’Souza, he has gotten by without contracting much of a headache.

The Role He Was Meant To Play

His success, in part, can be attributed to his personality. Lakshmi Narayanan, now the vice chairman of Cognizant, who not only preceded D’Souza in the corner office but also mentored him for a long time, says that the current CEO has the unique ability to focus on multiple things at the same time. “Taking charge of the emerging businesses was natural for him. He is personally passionate about technology. But he never lost sight of the other businesses. He was responsible for them. So he travelled a lot during this time, and kept his pace throughout,” Narayanan said.  D’Souza’s ability to manage multiple time zones, multiple horizons at multiple levels is a recurring theme during conversations with Cognizant employees. This isn’t surprising. The son of a diplomat, he attended seven different schools in six different countries across three different continents. He got his bachelor’s and master’s degrees from two ends of the world—one at the University of East Asia in Hong Kong and the other at Carnegie Mellon University, in the US. One of his colleagues used this phrase to describe how it is to work with him: “You have to be ahead of time to be on time.”

D’Souza’s ability to manage multiple time zones, multiple horizons at multiple levels is a recurring theme during conversations with Cognizant employees. This isn’t surprising. The son of a diplomat, he attended seven different schools in six different countries across three different continents. He got his bachelor’s and master’s degrees from two ends of the world—one at the University of East Asia in Hong Kong and the other at Carnegie Mellon University, in the US. One of his colleagues used this phrase to describe how it is to work with him: “You have to be ahead of time to be on time.”

Beyond D’Souza’s personality, the driver has been his manner of execution. Narayanan says that in any business, strategy itself is not the winner, execution is. Even a suboptimal strategy will yield fantastic results, if execution is fantastic. And the way D’Souza has executed his strategy has lessons for all.

First, create an operational structure that discourages short-termism. D’Souza was always interested in the question, ‘what is the ideal structure for a company’. Rajeev Mehta, his classmate at Carnegie Mellon and group chief executive, industries & markets, at Cognizant, remembers (in an interview for an earlier story) how “Frank” used to talk about a two-in-a-box structure even when he was a student, refining the theory over the years. His Three Horizons model was also equally thought through to ensure that management is not driven solely by the results of a single quarter: Emerging businesses should not have to give up their allotted investment because the other businesses were not doing well and demanded an extra push.

Second, build a team that gives you flexibility to move. D’Souza made sure he created a team that was diverse, experienced and motivated. The idea was to have a venture capital-like structure to manage the Emerging Business Accelerator (EBA) that formed the core of its third horizon. He picked only those who would be comfortable working in a startup environment—bringing in people from within Cognizant and hiring aggressively from outside. Venkateswaran, for example, helped incubate Cognizant’s manufacturing, retail and logistics, and also scaled it up.Mark Ivanowski, who was brought in from the outside, is a managing director at EBA he had extensive experience in the world of venture capital and startups. Tom Thimot, who heads market development at EBA, had previously served on the boards of startups besides heading a couple of them. When D’Souza had to take time away from H3, the team had no problem in handling it without him.

Third, don’t forget the small stuff. “Frank is like a Lytro camera. He can change the focus after the picture is taken,” says Venkateswaran, referring to the plenoptic cameras made by the US-based startup. Lytro manages to do this (letting users refocus after the picture is taken) by assembling a large number of micro lenses in addition to the regular lens. Together they catch the entire light field instead of just a 2D image, and the software does the rest.

Managing a multi-billion-dollar organisation is presumably more complex than the workings of a Lytro camera but, for D’Souza, one the biggest learnings from his time in crisis management is to never underestimate the importance of small things.

He says: “No matter how big, how great the crisis seems to be, you shouldn’t forget the small things. Like patting the back of a colleague who has done a good job, being home in time to put the kids to bed, spending 30-45 minutes a day in the gym. Those are the things you can’t forget. It’s easy to forget these things because the enormity of what you have to do is large, or seems to be large, and there is a tendency to say that ‘what we are doing is so big, so everything else is unimportant’. But in a crisis, these smaller things… they become more important.”

First Published: Oct 23, 2013, 06:59

Subscribe Now