How Formula 1 Racing Came to Texas

The vision guy got iced out. The bond trader and the billionaire took over. Will the new track be done in time? The sordid story of how Formula 1 racing came to Texas

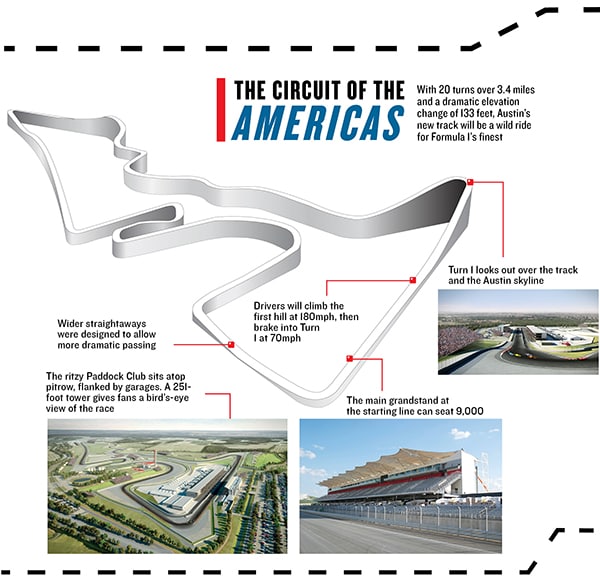

Bobby Epstein guns his Cadillac Escalade up a 130-foot incline, banking left into the hairpin of Turn 1. What’s terrifying at 180mph in a Formula 1 race car is, at one-quarter the speed in an SUV, a soothing break from reality. If he rolled down his window, the chairman of the Circuit of the Americas racetrack would be bathed in the dust and noise of 1,000 workers and heavy machines hustling to prepare the 1,100-acre site for the inaugural United States Grand Prix. The smooth asphalt blowing by quietly beneath us is just about the only thing fully completed.

The pressure is on: 100,000 tickets for the three-day race weekend, November 16–18, have been sold. The race promises to be a boon for Austin, better known for Willie Nelson, the University of Texas, and South by Southwest. The grandstand looks impressive, as does the Paddock Club—12 suites at 10,000 sq ft each—primed for the well-heeled who’ll pay at least $4,200 for the chance to watch 56 laps of the 3.4-mile track from just above the pits. Austin has cooked up the typical self-justifying statistics— the track will boost local business by $300 million a year, according to a study, and Epstein’s figures are still more ebullient ($500 million).

Yet, for all the excitement, Epstein, a 47-year-old bond trader whose idea of a good time is driving his RV around the country, finds himself something of a hostage. He never intended to end up as the biggest investor in a $450 million sports debacle or the central character in a two-year soap opera that pitted him and a San Antonio billionaire against a small-time race promoter.

But here he is, stopping his Escalade in the middle of the track to make sure I get a close look at the 251-foot-tall tower that will provide 100 people a bird’s-eye view of the whole shebang. Building it was his idea, part of a project into which he’s now personally sunk an estimated $50 million or more.

“When the stands fill with people it will feel a lot better than how it feels today,” he admits. “If you had told me up front there would be that many hurdles, I either would have been better prepared or I don’t know if we would have done it.”

The only-in-Texas saga of how F1 came to Austin starts with a guy named Tavo Hellmund. The son of a race promoter, he grew up locally, aspiring to be an F1 driver, and raced stock cars in the US and Formula Three in Europe. His real dream was to bring Formula 1 to Austin.

“I live and breathe racing,” says Hellmund, an intense 46-year-old who alternates spitting out profanities and tobacco juice. “And there’s nothing I wanted to see more in my entire life than a Formula 1 Grand Prix here in my own hometown.”

In 2007, Hellmund sketched out a track design, inspired by the best turns of tracks like Brazil’s Interlagos, England’s Silverstone and Turkey’s Istanbul Park. He brought the plans to Bernie Ecclestone, the billionaire chief executive of Formula 1—and a friend of his father’s.

Ecclestone has long been keen to increase the sport’s presence in the US. In the rest of the world, F1’s races generate $2 billion in revenues, bolstering prospects for an initial public offering that could raise $7 billion—or more, if F1 can get US investors excited. Back in 1982, there were three Formula 1 races in the US. But they faded away as Nascar and its oval tracks ascended the leftover twisty tracks were unable to keep up with the safety needs of ever more ambitious race cars. The last US race was at the Indianapolis Motor Speedway in 2007.

After what he says were maybe a dozen meetings and many more phone calls, Hellmund eventually coaxed a contract out of Ecclestone that granted him the rights to run a Grand Prix in Austin for 10 years. On some big conditions: He had to build a track, plus pay Formula 1 $23 million a year in sanctioning fees.

With that guarantee, Hellmund turned around and cut what he thought was a solid deal with the state of Texas to tap the Major Events Trust Fund (used to help attract perceived economic boons like the Super Bowl) to pay those $230 million in sanctioning fees over 10 years.

Hellmund priced out how much it would cost to build a raceway—be- tween $200 million and $250 million, he guesstimated—and then set out to find some local deep pockets.

He quickly found Epstein. Little known outside of Austin, Epstein established himself as a bond trading researcher at Dain Rauscher in 1992, he started and then sold his own broker-dealer, and then founded Prophet Capital Management in 1995. His hedge funds now manage $2 billion.

Epstein, who had been to only one F1 race prior to his involvement, is a thin, cerebral guy from Dallas, who regularly lunches at Wild Bubba’s Wild Game Grill near the track (try the long-horn burger). When he met Hellmund, Epstein was looking for something to build on land he owned outside of town his plan to build 1,200 homes succumbed to the real estate crash.

Hellmund’s F1 contract and state-subsidised windfall looked appealing.

One thing Epstein didn’t want was the spotlight, so he sought out a higher-profile partner with experience in cars and sports. Billy Joe ‘Red’ McCombs was a natural fit. The billionaire built up a chain of auto dealerships in San Antonio before making his $1.3 billion fortune as an early investor in Clear Channel Communications. At various times, he’s owned the Minnesota Vikings, San Antonio Spurs and Denver Nuggets. “When you think about sports, showmanship and Texas, it’s a short list that leads you to Red,” says Epstein.

At 84 and in the process of handing over his empire to his daughters, McCombs was more averse to risking millions on a wild ride, but he liked Epstein and he liked the project. “It’s something that I ordinarily wouldn’t do, but I recognised that the people who had it didn’t have a chance to get it done,” he says, referring to Hellmund. “Didn’t have a chance.” In July 2010, Hellmund, McCombs and Epstein started a new partnership, Accelerator Holdings. In exchange for a 20 percent share, Hellmund would chip in his F1 contract and another deal to host a MotoGP motorcycle race, both to be underwritten by those millions in state funding. For their 80 percent, McCombs and Epstein pledged to raise a minimum of $190 million by March 31, 2011.

But what looked good on paper went south—quickly. The parties have differing versions, but documents and conversations with people in the know weave a fairly consistent narrative.What’s clear is that in plunging ahead with groundbreaking in December 2010, McCombs and Epstein made two blunders familiar to all those who’ve ever fallen blindly in love with a business idea: They began investing their money and reputations before they figured out how to make a profit, and they neglected to tie up legal loose ends.

When the March 31, 2011, day of reckoning arrived, Epstein and McCombs were not ready to inject $190 million into the risky project. Hellmund says he was eager to assign his contracts as soon as his partners fulfilled their financing obligations and proved they had access to enough cash to get the job done.

Meanwhile, the clock was ticking: Ecclestone had penciled in June 17, 2012, as the date of the inaugural US Grand Prix at Austin. Both sides had leverage. Hellmund’s partners were already pregnant with the project, having put up a few million to start construction. Epstein and McCombs knew Hellmund had little option but to cooperate and sign over his contracts— where else could he hold his race?

But despite being bound together, the marriage soured. Hellmund claimed he was barred from seeing financial statements and cut out of decision-making, even the hiring of Steve Sexton, former president of Churchill Downs, as the Circuit of the Americas’ new president. He griped that his promised salary of $500,000 and position as the chairman of the US Grand Prix failed to materialise. (The company denies all of these claims.)

“He wanted to run the business as a race, versus running it as a multi- dimensional company,” says Epstein, referring to Hellmund and the decision to bring in Sexton, despite his lack of car racing experience. Under Sexton, the track made a deal with Live Nation to bring concerts to the 15,000-seat amphitheatre on site. The grandstand area can be transformed into a soccer pitch or tennis court.

Those close to the relationship say that Hellmund’s behaviour became more erratic. Track employees say weeks passed during which they never saw him in the office. Sources say Hellmund was convinced that his email was being hacked, that he was being followed, that his partners were trying to cheat him. Hellmund declines to comment on any of this.

The project lurched forward despite the legal limbo and dysfunction. Costs skyrocketed. Expensive soil remediation was required, and a gas line had to be moved. The city council endorsed the project on the condition that the track put up $5 million to fund green technologies. At $450 million, the track will cost double Hellmund’s original estimate.

Slow, underfunded construction meant there was no way the track would be ready by the June 2012 race day. Ecclestone agreed to move the race to November. But he was running out of patience Ecclestone still hadn’t received the $23 million sanction fee to make Hellmund’s contract valid—and Hellmund still hadn’t signed it over to the partnership.

But although moving the race date bought them time, it messed up the deal with the state, which by law couldn’t hand over cash more than a year before the event.

Late last summer, the dysfunction came to a head. Hellmund claims he had cobbled together a new group of investors to replace Epstein and McCombs. “I offered to buy them out,” says Hellmund. “They refused.” Epstein says they “never received a verifiable offer from Mr. Hellmund”. Epstein and McCombs instead agreed to pay Hellmund $18 million for his shares in the track—and for his F1 and MotoGP contracts.

Yet again, a deal on paper didn’t get signed. “We were prepared to pay a large sum of money for valid contracts,” says Epstein, regardless of whether the sanction fees had been paid. Sources say Epstein went to London to clear the buyout with Ecclestone, who might have thought it odd that the man who dreamed of a Grand Prix in Austin and had been touting himself as the face of the project would want to walk away from it. Ecclestone’s response: Work it out with Hellmund.

But they didn’t. Worse, on November 15, 2011, Texas Comptroller Susan Combs, bowing to political pressure, announced that no taxpayer handout would be paid before the race at all. They would have to find another way to underwrite the sanction fee.In November 2011, Epstein and McCombs halted construction. It made no sense to keep building if they didn’t legally have a race to run in November. Epstein again approached Ecclestone, seeking to persuade him to cancel Hellmund’s contract (which was in breach for non-payment). And again Ecclestone stood by his friend’s son, reportedly accusing Epstein and McCombs of “trying to steal” the race from Hellmund. He also publicly threatened to pull the race entirely.

In the end, Ecclestone agreed to issue the Circuit of the Americas its own 10-year contract—at a price. He upped the annual sanction fee to $25 million instead of the previous $23 million. “Bernie is a master negotiator,” says Epstein.

“I’ve made a big effort to make sure this race happens,” Ecclestone tells Forbes. “I never had any problems or doubts. The doubts were all on their side.”

The circus didn’t end there. Epstein had succeeded in getting a new F1 contract without paying off Hellmund. But Hellmund still had his interest in the company.

Even though their contracts called for disputes to be resolved in arbitration, Hellmund sued his partners in March, accusing Epstein and McCombs of wilfully ignoring the terms of their contracts. Rather than get bogged down in a court fight, Epstein and McCombs finally settled with Hellmund in mid-June—for considerably less than the $18 million proposed payout, according to sources familiar with the deal. Asked about Hellmund’s payout, Epstein says, “I’m willing to be patient for success, and not everybody is willing to be patient.” Now, with the race finally at hand, some semblance of normalcy has returned. Hellmund is out. McCombs, too, has dialled back his involvement and capped his equity contributions but is believed to be a guarantor behind much of the track’s debts. Epstein, meanwhile, has attracted more than a dozen new equity investors, including Paul Mitchell/Patrón billionaire John Paul DeJoria. Racing legend Mario Andretti was hired as the public face of the track.

The state’s largesse also seems poised to return. After meeting with Texas Governor Rick Perry at the Italian Grand Prix this year, Epstein says he’s finalised a deal by which Texas will reimburse the track for the F1 sanctioning fee after each year’s race, once the receipts from the horde of F1 fans have been tallied up. In time, Epstein hopes to build a hotel and research centre on site, as well as garages for the rich and fast to park their Lamborghinis and Ferraris.

“I never envisioned taking charge of the project,” says Epstein, much less infusing all that cash. Worth it? “Bonds are great. They don’t talk back. They work on weekends. They don’t require you to go talk to the city, the county, the state,” he says. “But the emotional satisfaction and the mental challenge that I get from a project like this is nothing I’ve experienced before.”

And Hellmund? He says he’s currently pursuing a new Formula 1 contract with partners in Mexico— an idea that would put him in direct competition with Epstein and McCombs, who are counting on racing fans to trek north of the border.

Come race day, though, he promises he will be trackside. “I spent my whole life figuring out how to bring F1 to Austin,” says Hellmund. “I wouldn’t miss it for the world.” And what about his former partner, Epstein?

His only response: “Who?”

First Published: Nov 20, 2012, 06:55

Subscribe Now