Chasing the Deals in China's Crowded Private Equity Market

Foreign private equity firms are not able to ride the China private equity boom like they once did

Foreign private equity in China is down, but far from out.

For most people, having too much money in the bank is hardly a concern, particularly in the current economic climate. For those in the private equity (PE) industry, however, it’s a an unpleasant reminder of how much the world has changed since the go-go years of the PE boom from 2005-2007.

As of the end of last year, the industry was sitting on around $900 billion of unused capital, or “dry powder” in the industry jargon, according to Preqin, a research outfit. The reason is that managers are investing far less than they used to. While global figures are patchy, the total volume of PE transactions in the US market alone dropped from $405 billion in 2007 to just $88 billion last year.

It’s not hard to see why executives are reluctant to deploy their capital. Credit–the lifeblood of leveraged buy-outs–is a shadow of what it was before the economic downturn. And the global landscape is dismal: growth in the US is hovering at a paltry 2%, while Japan and Europe are flirting with another recession.

China is the exception. Growth has certainly slowed this year, but at around 7.5%, it is still well ahead of the developed world and other large emerging markets like India (expected to grow about 5.5% this year) and Brazil (2.5%). Small wonder private equity deal-making in the country rose almost 10% to hit a record high of $15.2 billion last year, according to a report by the consulting firm Bain & Co and Asian Venture Capital Journal (AVCJ).

But foreign private equity firms are not able to ride the China private equity boom like they once did. Over the past five years, new regulations have restricted their investment options. The industry has also become much more competitive due to a surge of small, well-connected domestic PE firms. But with so few other fast-growing markets in which to put their money, foreign private equity firms are looking to adapt, rather than exit, the Chinese market.

Crowding the Field

Foreign private equity funds are no strangers to the Chinese market, and some have proven talented money-makers. To take just one example, a consortium of private equity buyers including Blackstone, Morgan Stanley and Goldman Sachs were early minority investors in Ping An Insurance, now one of China’s biggest insurance and financial services firms. In 2005 the group sold a 9.9% stake in the firm for $1 billion, posting a healthy 1,300%-plus return on its initial $70 million investment.

Besides business smarts, foreign PE firms have benefitted in the past from the lack of traditional (i.e. bank) financing available to many small and medium-sized businesses in China, as well as opportunities to pounce on badly-run state-owned enterprises sold off during the 1990s and 2000s.

Today the field has become much more crowded, and making stellar returns is a lot harder. “If you look at the investments that were made within this time [before around 2007], there was far less competition,” says Liu Jing, Professor of Accounting and Finance at Cheung Kong Graduate School of Business. “Firms now have to compete for a limited number of deals, and prices are increasing.”

The biggest impact has been the explosion of homegrown PE firms. China’s National Reform and Development Commission (NDRC) officially recorded 882 Chinese private equity and venture capital firms as of the end of 2011, with assets of almost RMB 220 billion ($35 billion). The true figure, however, is likely much higher. Liu of CKGSB reckons there to be around 3,000-4,000. Jonathan Zhu, Managing Director at Bain Capital Asia, said at a forum in Beijing in March that there could be as many as 20,000. “I’d be happy with 8,000 competitors,” he quipped wryly, no doubt reflecting the feeling of many foreign PE firms.

New Kids on the Block

The surge is due at least in part to government design. Beginning in 2006-2007, both Beijing and local governments took a series of steps intended to cultivate a domestic PE industry. The idea, argues Chris DeAngelis, a Beijing-based principal at Alliance Development Group, was to keep the entire process within China–everything from raising funds from Chinese individuals to investing in Chinese companies and eventually listing on Chinese markets.

To that end, the government allowed PE firms to raise yuan-denominated funds and changed their legal status from corporate investment houses to limited partnerships, effectively allowing them to fundraise from wealthy Chinese individuals. The government also began closing loopholes that allowed Chinese companies to accept US dollar-denominated funding from foreign PE firms via offshore holding entities. The clampdown did not totally block the channel, but it did make the process much slower and more cumbersome.

The upshot is that the playing field has clearly tilted in favor of domestic funds, which have important advantages of their own. For one, they are often well-connected, giving them access to the best deals. One China-based analyst covering the industry, who declined to be named because of the sensitive nature of the topic, says that many of the smaller Chinese PE funds are so intertwined with local officials that they are now “more or less de facto agencies” of local governments.

Beyond better connections, these firms can be more nimble than their big foreign rivals–not just in quickly sourcing and signing new deals, but also in terms of the speed at which they can get their yuan-denominated funding into company coffers. DeAngelis of Alliance Development Group notes that investing dollar-denominated PE funding into China is simply logistically difficult. “China doesn’t have the [regulatory] structure to deal with [foreign PE firms].”

The Equity Strikes Back

Yet foreign PE firms are hardly throwing in the towel in the face of stiffer competition and tougher regulation many still have big competitive advantages. For starters, the likes of the Carlyle Group, TPG, KKR and Blackstone are more experienced than all but the biggest Chinese PE firms, and boast some of the world’s best talent at spotting and growing promising start-ups.

Moreover, American and European PE firms can borrow capital much more cheaply than their Chinese competitors, thanks to ultra-low interest rates across the developed world. Their huge size also gives them access to big deals, important because the vast majority of Chinese PE firms compete at the smaller end of the market.

“The nature of Chinese PE is very different from its international counterpart”, says Joseph Chan, a Shanghai-based partner at the law firm Sidley Austin, who works on private equity deals. “Internationally, one deal could be massive, and [that] is the traditional model.” In China, by contrast, he says a typical investment might be just $50 million–a small sum by Western standards.

Many foreign PE firms have also teamed up with local Chinese governments to mitigate their regulatory disadvantages. Carlyle has raised yuan-denominated private equity funds in partnership with both the Beijing and Shanghai municipal governments TPG has also partnered with Shanghai, and Goldman Sachs is working with Beijing, among other tie-ups.

Furthermore, the big global players have taken to scouring non-traditional sectors for investment opportunities. “Focus has diversified,” says Chan.

For example, he notes that many of the foreign PE investments in the past were focused on China’s technology sector. He cites Ctrip as a typical case the online travel site has received investment from foreign private equity firms such as Morningside Technologies, Tiger Global Management and others. (Its rivals, such as Elong and iTour, have also received plenty of PE funding.) As new Chinese funds have flooded in, however, the sector has become too crowded, deals too pricey and many foreign players are now turning their attention elsewhere.

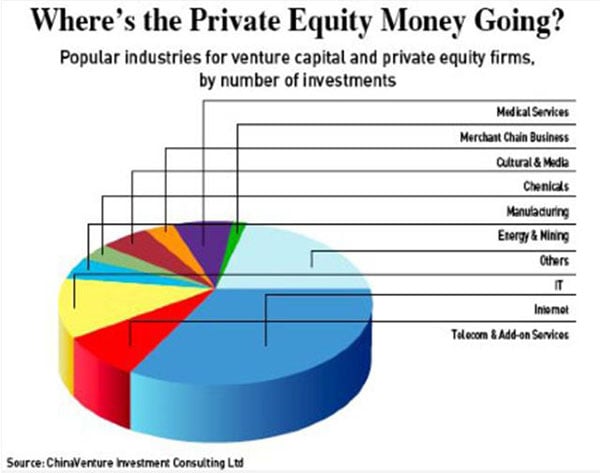

One of these areas is clean technology. Five of the 10 biggest IPOs in China last year were exits from clean-tech deals. A further 11 deals worth $2.6 billion were exited via IPOs on global markets, including blockbusters such as Goldwind’s $920 million IPO in Hong Kong. Chan notes that besides the economic case for investing in renewable energy, the industry is also an important beneficiary of the government’s 12th Five-Year Plan. “Anything in new materials and clean tech will be important–investors can expect a lot of subsidies and tax breaks,” he says.Private equity in China is largely directed to the IT, internet and telecom sectors

One Eye on the Exit

To be sure, serious challenges remain. In a report on China’s private equity industry in 2012, Peter Fuhrman, Chairman of China First Capital, argued that future returns in China’s PE industry could decline substantially due to shrinking opportunities for PE firms to cash out companies on stock markets.

The reason lies in the nature of PE exits in China. “In a market like the US, around two-thirds of exits by [private equity or venture capitalists] are a form of M&A–you fund the company, and it will eventually be bought by a big player like Microsoft,” says Chan of Sidley Austin. In China, by contrast, “it’s all about IPOs,” which have become much less attractive than they once were.

Valuations of companies on mainland Chinese stock exchanges are still high, but regulatory approval to list is hard to come by. Meanwhile, valuations for Chinese companies listed in the US and even Hong Kong have sagged in recent months. Ernst & Young, a professional services firm, attributes a decline in the number of PE deals in China this year to weak investor sentiment in global stock markets.

Still, for all the challenges, few foreign PE firms are backing out of China. Quite the opposite: a 2012 report by Bain and AVCJ found that many foreign PE firms including Carlyle have reacted to a tougher environment by increasing their staff on the ground in China, in order to scope out deals others may have overlooked. One out of every 12 employees at Carlyle, for example, is now based in China.

It’s not hard to see why. With the rest of the world either facing anemic growth prospects or even recession, China still has more potential investments than just about anywhere else. Bain Capital estimates that the private equity industry still has about $43 billion in “dry powder” targeted specifically at China. The shots may be fewer and more carefully aimed than they once were, but foreign PE firms are likely to keep taking shots in China for a long time to come.

First Published: May 15, 2013, 07:02

Subscribe Now