Will Neal Patterson make Americans Healthier?

With a big boost from Washington, Neal Patterson’s futuristic vision for computerised health care has made him a very rich man. But will it make Americans healthier?

North Kansas City is an unlikely place to launch a revolution in American health care. Yet here, amid the dilapidated grain elevators, fast food joints and vast green plains, the dream of using computers to keep you alive at a reasonable cost is battling onward. In a bunker-like building built to withstand a direct hit by a category five tornado, 22,000 servers handle 150 million health care transactions a day, roughly one-third of the patient data for the entire US. Records of your blood pressure, cholesterol, lab test results, that gallbladder surgery last year—and how much you paid for it—may sit there right now. Armed guards stand watch.

This is a data centre at the headquarters of Cerner, the world’s largest stand-alone maker of health IT systems—and company number 1,621 on Forbes’ Global 2000 list—where the blood-and-guts realities of medicine meet the sterile speed and exactitude of the computer revolution.

For 33 years founder and Chief Executive Neal Patterson has preached better health through information, a world in which powerful digital machines right out of Star Trek link hospital bedsides with real-time data on what ails the entire nation, finding patterns, suggesting treatments—and tracking costs. Patterson, 62, has likened the journey to pushing a “500-pound marshmallow up a hill” but now insists that health care’s moment of digital transformation has arrived. “It is finally happening,” he says. “Without a doubt in my mind, it is happening this decade.”

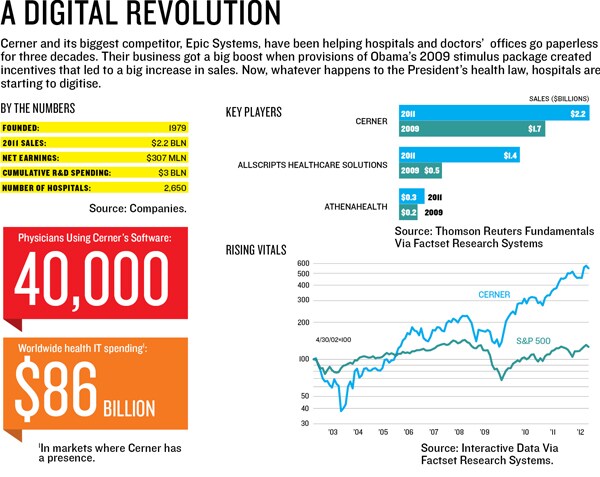

It would certainly seem so from Cerner’s financials. Over the past five years sales have grown an annualised 9 percent and earnings 22 percent. Last year, the company booked $307 million in profits on sales of $2.2 billion. Since Patterson started Cerner in 1979 it has been consistently profitable, and shares have increased at an annualised 22 percent since a 1986 IPO. That’s 11 percent better than the S&P 500 over that 26-year span. The appreciation of Cerner’s shares has made the frugal Patterson a very rich man. His Cerner stake is worth $1 billion.

Patterson’s innovations in computing and data storage certainly helped fatten that number. But Washington, especially President Barack Obama, has given him a healthy boost. As the rest of the economy floundered, Cerner boomed, thanks to a 2009 law that was Obama’s first foray into health care.

Those that meet certain milestones, such as using computer systems to order medicines, detect deadly errors and keep patient records, get payments. Any hospital that doesn’t have “meaningful use” of IT by 2015 will face a cut in reimbursements. It’s a market-based system, because it allows hospitals to choose among rivals such as Cerner, Allscripts and General Electric, but it practically forces everyone to buy something, at a cost of up to $30 million per hospital—and that’s without the extra IT staff they need to hire. This made health IT one of the hottest hiring sectors of the whole economy. Cerner’s workforce grew 20 percent to 10,500 employees in the past year, and the company is opening a new 660,000-square-foot office complex in Kansas City to hold 4,000 more employees.

The best part for Cerner and rivals like closely held Epic Systems: No matter what happens to Obama Care, now facing potential overturn at the hands of the Supreme Court, there’s little likelihood their business will be hurt. “Look, I’m a Republican,” says Bernard Birnbaum, vice dean and chief of operations at NYU Langone Medical Center in New York City. “Regardless of what happens in the election and regardless of what happens in the Supreme Court, we’re off to the races.” Why? Health costs are ramping up too fast. “You need well-implemented electronic health records,” he says.

“You need to manage the data.” This is Patterson’s basic line, too: The trajectory of health care in America and elsewhere is set.

Cerner will experience truly stunning growth if he’s right. Only 3.5 percent of the $2.5 trillion now spent on health care in the US goes to IT, of which 2.6 percent goes to Cerner. By the end of the decade, the company estimates, sales could perhaps double, to $5 billion, or even quadruple, to $10 billion.

Patterson literally came out of the wilderness, growing up on a wheat farm on the Kansas-Oklahoma border in an area so sparse that he was rushed into first grade so there would be two boys, not just one. In 1973, after Oklahoma State (his generation was the first in his family to go to college), he took a job as a consultant at Arthur Andersen in Kansas City. He liked the idea of moving between industries. He was, essentially, a hired-gun computer programmer.

“Basically what we were doing then was companies would buy a computer and they would need software,” says Patterson. “I designed and developed an unbelievable number of applications early in my life. So we were sitting there saying, ‘The software industry is going to be a major industry.’”

He and two Andersen buddies, Clifford Illig and Paul Gorup, decided to take the certified public accountant tests just to show up Andersen’s accountants. (Only Gorup passed.) While studying at a picnic table in a park, they decided to start a company. In 1979 Patterson, then the breadwinner for a growing family, quit to make good on their idea, calling the company PGI & Associates. They weren’t sure what kind of software they would write. The first job that came in was from a large group practice of pathologists, the doctors who look at tissue samples to try to figure out why you’re sick. Health care had chosen them.

It was a strange business. The pathologists “thought I walked on water because I understood computers,” says Patterson—a technophobic stance for a bunch of specialists with advanced degrees. But he thought that if the automobile industry could be automated, so could medicine—the opportunity seemed huge and immediate. Patterson raised $3 million in venture capital and in 1984 launched PATHnet, a pathology computer program that grew out of his earlier work. They needed to change the name to raise money and picked Cerner, an obscure Spanish word meaning to sift, because Patterson’s wife liked it.

By 1986, Cerner was generating $17 million in annual sales and raised $16 million in an IPO. “It was very small by any standard,” Patterson quips, “except for if you were the farm boy from Oklahoma, it looked like a lot of money.”

It was a cottage industry with weird, even perverse, incentives. The people who had to use Cerner’s software weren’t the ones who decided to buy it. Hospital departments made the decisions to spend the hundreds of thousands or millions of dollars for computer systems—the doctors themselves were but independent contractors. So there were computer systems for lab results, for running pharmacies and especially for billing, but nothing that made physicians’ lives better. Health care IT remained a small business in which the solutions that worked elsewhere in computers—PCs, spreadsheets, general purpose software—didn’t fit. Data had to be kept private, yet had to be shared within the hospital. The tried-and-true was more valuable than innovation. Computers also didn’t yet seem powerful enough to have a meaningful impact on health care problems. Big entrants such as Microsoft, Apple and IBM had little interest.

As early as 1994, Patterson was trying to change this, ultimately investing $350 million to unify all of Cerner’s computing products into one. But except for the Mayo Clinic, where the doctors actually do work directly for the hospital and where the idea of an integrated health records system had taken root, there wasn’t tremendous interest.

In 1999, a report from the prestigious Institute of Medicine gave Patterson hope that the rest of medicine was ready to follow in Mayo’s footsteps. Titled “To Err Is Human,” the report detailed how between 44,000 and 98,000 people die every year in hospitals from preventable mistakes, like getting the wrong medicine or the wrong dose of the right one. The report specifically prescribed better computer systems as a way to prevent these deadly mistakes. Patterson cites that study as the moment when health IT entered the mainstream.

But it was still slow going, and that drove him nuts. His customers at that time were more worried about the Y2K bug than they were about revolutionising health care. One morning he walked into work and penned an infamous e-mail to a large group of Cerner’s managers for letting employees slack off, and he threatened retribution. “Hell will freeze over before this CEO implements ANOTHER EMPLOYEE benefit in this culture,” Patterson vented. “The parking lot is sparsely used at 8 am likewise at 5 pm. As managers you either do not know what your EMPLOYEES are doing or YOU do not CARE. ... What you are doing, as managers, with this company makes me SICK.”

The e-mail leaked onto a Yahoo message board and was published by the BBC, the Wall Street Journal and everywhere else. Patterson regrets only that he included many people on it who did not have personal experience working directly with him.

The real problem was that “the systems were not ready for widespread adoption,” says David Westfall Bates, the Harvard professor who was the lead author of the Institute of Medicine report. And the problems that needed to be solved were maddeningly specific and very different from the e-commerce issues that were being routinely cracked by Google and other sites at that same moment. A bank only has to worry about money, Bates says, but an average hospital IT system must track 6,000 variables.

Worse, says Bates, only half of the financial benefits of installing a health IT system go to the hospital. For a doctor’s office it’s even worse, with the doctor having to foot the whole bill and getting only 10 percent of the benefits. Small, specialist companies like Cerner and Epic are good at the service business of working with doctors and hospitals frustrated by the trail of tears necessary to get a working IT system in place. “It’s their niche,” Bates says.

Beyond financial matters, sometimes putting in a big computer system may even do patients harm before it can do good. When the Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh installed a Cerner digital drug-ordering system to replace its old paper one in late 2002, the medication error rate declined—except for kids who had been transferred from other hospitals. Five months after the new system was installed, the death rate for these children had doubled. In a controversial 2005 paper in Pediatrics, a group of doctors at the medical centre blamed a complicated user interface that required up to ten mouse clicks and several minutes for a single drug order. Cerner disagrees about the software’s role in the problem everyone agrees that it was fixed and that mortality is now lower than it was under the old paper system. But the Hippocratic oath says nothing about breaking eggs to make omelettes.“We’re kind of headed in the wrong direction,” says Scot Silverstein, a health IT expert at Drexel University who believes that the current systems are too prone to randomly losing data and complicating doctors’ lives.

The huge obstacles to getting an electronic prescribing and health system up and running were on clear display when Cerner’s public relations people brought me to Truman Medical Center, the teaching hospital associated with the University of Missouri-Kansas City School of Medicine. Doctors there treat underserved Medicaid patients and lots of serious trauma. In an intensive care unit a nurse showed me how she read patient records off a computer terminal in the room and made sure that she was giving patients the correct medicine at the correct dose using a bar code scanner.

Unlike the fast, gorgeous touchscreen interfaces that Cerner shows off at its campus, this program looked klutzy and ran on a PC. The nurse was a pro—she had just been promoted to a position in which she’ll train others to use the software. But she admitted that, at first, a lot of doctors had made mistakes using the system, such as writing prescriptions in fields where nurses could see them but pharmacists, who actually dispense drugs, could not. Still, the verdict was that the system was cutting down on mistakes and having other benefits, too: It got pharmacists out of the pharmacy and onto the hospital floor, where they caught errors, and allowed doctors to check on patients from home.

With all this natural institutional stasis, it required a government push to get hospitals to step gingerly toward the future. Patterson, a registered Republican and Ayn Rand devotee, says that the 2009 law has done something even more important: It sets standards for what types of tasks—ordering prescription drugs, pooling patient data, giving patients access to their records—hospitals must accomplish. The law’s impact on his business is inarguable. Sales booked in 2011 were $2.7 billion, up 50 percent in three years. Cerner stock is up fivefold, a bigger percentage increase than in the entire previous decade. Now the mantra at the company, in the words of Cerner chief of staff Jeff Townsend, who has been at Patterson’s side for 15 years, is “Don’t waste the gift.”

Cerner’s new offerings, on display at its gleaming headquarters with a heavy dose of skilled salesmanship, have the whiff of the future. The company is giving hospitals, for free, software to help predict which patients will get deadly, hard-to-treat blood infections. A new type of patient record is quickly and automatically searchable, even if the data go back decades. A fictional case study shows how a heart attack patient could be cared for in this new system, starting with wireless monitors that he’s wearing when his heart rate speeds up through a visit with a nurse who talks to specialists using an iPad and FaceTime to improved versions of the bar-code-reading devices at Truman.

At least Cerner eats its own cooking. In 2005, Patterson abandoned using an outside health insurer and hired his own doctors to take care of Cerner employees. Employees can access their medical records from home, and doctors’ visits happen in front of a giant flat screen where the patient can see the doctor’s notes as they’re inputted.

“Insurance companies as they exist today are going to be eliminated,” predicts Patterson. Either the current insurers will evolve into something new or, possibly with the help of ObamaCare, which creates new exchanges for selling health plans, big hospital systems will offer their own plans.

All this is right in line with what many other health futurists are predicting. Eric Topol, the chair of innovative medicine at the Scripps Research Institute, lays out a similar road map in his book The Creative Destruction of Medicine. He praises Cerner for “thinking big and getting into wireless sensors” and says both Cerner and Epic will figure out that they need to capture all the relevant information, from imaging to real-time sensor data, for every patient. But he warns that just as electronic health records have been “more complicated and painstaking than anyone would have forecast,” so, too, will the next stage be “Darwinian.”

Harvard’s Bates, whom Patterson credits with putting medical IT on the map, thinks it’s even possible that we’re reaching a stage where big names like Microsoft and Google could finally move into the health care industry, exploding the niche that has protected Cerner and its rivals for so long. Patterson says he isn’t worried at all—he’s ready for revolution. “There is going to be fundamental change that’s going to happen,” he says, “but the elements of that change are all here today. And it’s going to be better for almost every participant.”

Epic Systems: Marketing Sucks

Neal Patterson isn’t the only health care IT billionaire in America. He’s not even the richest. That title belongs to Judith Faulkner, 68, the iconoclastic chief executive and founder of Epic Systems of Verona, Wisconsin, a secretive private company nestled in what it calls its Intergalactic Headquarters on 800 acres of farmland. She once appeared in leather chaps alongside a Harley-Davidson in front of 6,500 guests. Epic has sales of $1.2 billion, and Forbes estimates Faulkner’s net worth at $1.7 billion. She has built Epic without outside capital and no marketing, rebuffing an attempt by her biggest client, Kaiser Permanente, to get a piece of equity when her company was much smaller. A Democratic donor, she also sits on a government-appointed panel that makes recommendations on standards for health IT.By next year 40 percent of the US population—127 million patients—will have their medical information stored in an Epic digital record. Faulkner has amassed her wealth by carefully choosing her customers and eschewing salespeople—1 percent of its 5,200 employees are in sales. Marketing folks once flashed a PowerPoint at an internal presentation that said: “Marketing Sucks … Epic Systems.” Faulkner commands her salespeople to approach only customers who are a good fit with Epic and turns down customers who don’t meet her standards. “They don’t need salespeople customers come to them,” says Leo Carpio, a health IT analyst at Caris & Co.

The biggest win: A $4 billion project to digitise medical records for health care giant Kaiser Permanente. In 2003, Kaiser narrowed the list of potential contractors to two: Epic and Cerner, which was three times as large. John Mattison, Kaiser’s chief medical information officer for southern California, called Cerner’s salespeople “suits” when a team of Kaiser doctors, nurses and IT specialists fanned out to visit hospitals, Cerner selected the people the team could talk to. Epic didn’t interfere. When Mattison and his team tried to break away from the scripted presentation, they heard less than flattering comments about Cerner, while customers praised Epic. “For me that was major, to be free to talk,” says Mattison. “They treated you like a colleague, not a customer,” says Jack Cochran, who heads the Permanente Federation, which represents Kaiser’s physicians. “They don’t sell you.” The revenue gap between Cerner and Epic is narrowing, and 260 hospitals, including top names like the Cleveland Clinic, NYU Langone Medical Center and almost the entire University of California system, have gone Epic.

Here’s proof of value: Epic doesn’t even negotiate on price. When it made a $200,000 pricing error in its contract with Edward Hospital in Naperville, Ilinois, it asked the hospital to fork over the amount in full. “They said, ‘All our customers are special we don’t give anybody special treatment,’” says Bobbie Byrne, the hospital’s vice president of health information technology. The hospital stuck with Epic.

Faulkner is not eager to telegraph her wealth and power, and turned down our request for an interview. “She doesn’t want the spotlight on her,” explains her spokesperson. Interviews with people who know Faulkner paint a picture of a forceful yet modest woman. Leonard Mattioli, an Epic board member, recalls chiding Faulkner for driving an old Volvo.

“I told her next time you buy a car, take a man with you,” says Mattioli, the founder of American, a midwestern retailer of appliances and electronics. A few years later Mattioli introduced his fiancée to Faulkner, who proceeded to pepper her with questions Epic typically asks prospective employees: “How many square yards of Astroturf are there in the US? Which person, dead or alive, would you most like to have lunch with?” Turning to a bewildered Mattioli, Faulkner said, “Next time you take a wife, take a woman.”

—Zina Moukheiber

First Published: Jun 08, 2012, 06:11

Subscribe Now