Prince Alwaleed: Saudi Arabia's Insecure Billionaire

Prince Alwaleed says he's one of the 10 richest people in the world. Forbes doesn't buy it

Any reporter who shows an interest in Prince Alwaleed Bin Talal of Saudi Arabia can expect at some point to get a little gift from His Royal Highness. A driver will courier over a thick, tall green leather satchel, embossed with the oasis palm logo and name of Alwaleed’s Kingdom Holding Co, weighing at least 10 pounds. Like Russian nesting dolls, the green leather satchel reveals a green leather-bound sleeve, which in turn encases a green leather-bound annual report. About the only thing not shrouded in leather are thin versions of a dozen of the best-known magazines in the world, each boasting the prince on its cover.

These magazines are the most telling items within the prince’s big-bucks information dump. Fronting Vanity Fair, he strikes a jet-set pose, complete with reflective sunglasses, a powder-blue sports coat and an open-collar shirt. He’s on two Time 100 covers, once in a collage with the likes of George Soros, Li Ka-shing and Queen Rania, and a second solo, donning the classic Saudi thobe and ghutra. There’s even a Forbes, from which he stares out powerfully, in a Steve Jobs black turtleneck, above the text ‘The world’s shrewdest businessman’. But the most instructive piece of information is consistent across them all: None are real. Rather than simply send out press clippings, the prince’s staff has concocted or rejiggered magazine covers, which they bind atop article mentions on beautiful high-gloss paper.

Image is everything to Prince Alwaleed, with speciï¬c care paid to those who can provide outside validation. He meets with very important people. Just ask him. His staff issues a press release with a photo seemingly every time he interacts with someone big (Bill Gates), someone who might someday be big (Twitter CEO Dick Costolo) or just someone who sounds big (Burkina Faso’s ambassador to Saudi Arabia). In 2003 he was photographed behind George W Bush, Jordan’s King Abdullah, Saudi Crown Prince Abdullah and Egyptian President Hosni Mubarak. When his authorised biography, Alwaleed: Businessman, Billionaire, Prince, appeared in 2005, that photo appeared on the back cover—this time with Alwaleed in front, courtesy, the prince later admitted to Forbes, of Photoshop. For several months beginning in late 2011, the prince even began blind copying me almost daily on text messages he sent: Some were to the spouse of a European president others to a well-known CEO at a large US technology ï¬rm still more were to the hosts of several cable-TV talk shows. The contents were shared off the record—but the intent to impress was not.

In terms of outside validation, though, his paramount priority, according to seven people who used to work for him, is Forbes’ list of global billionaires. “That list is how he wants the world to judge his success or his stature,” says one of the prince’s former lieutenants, who, like almost all his ex-colleagues, spoke on the condition of anonymity for fear of reprisal from the Arab world’s richest man. “It’s a very big thing for him.” Various thresholds—a top 20 or top 10 position—are stated goals in the palace, these ex-employees say.

But for the past few years former Alwaleed executives have been telling me that the prince, while indeed one of the richest men in the world, systematically exaggerates his net worth by several billion dollars. This led Forbes to a deeper examination of his wealth, and a stark conclusion: The value that the prince puts on his holdings at times feels like an alternate reality, including his publicly traded Kingdom Holding, which rises and falls based on factors that, coincidentally, seem more tied to the Forbes billionaires list than fundamentals.

Alwaleed, 58, wouldn’t speak with Forbes for this article, but his chief financial officer, Shadi Sanbar, was vociferous: “I never knew that Forbes was a magazine of sensational dirt-digging and rumour-ï¬lled stories.” Our discrepancy over his net worth says a lot about the prince, and the process of divining someone’s true wealth.

The prince first came on Forbes’ wealth-hunting radar in 1988, a year after our ï¬rst Billionaires issue came out. The source: The prince himself, who contacted a Forbes reporter to let him know just how successful his Kingdom Establishment for Trading & Contracting company was—and to make clear that he belonged on the new list.

That outreach proved to be the ï¬rst in what is now a quarter-century of intermittent lobbying, cajoling and threatening when it comes to his net worth listing. Of the 1,426 billionaires on our list, not one—not even the vainglorious Donald Trump—goes to greater measure to try to affect his or her ranking. In 2006 when Forbes estimated that the prince was actually worth $7 billion less than he said he was, he called me at home the day after the list was released, sounding nearly in tears. “What do you want?” he pleaded, offering up his private banker in Switzerland. “Tell me what you need.” Several years ago he had Kingdom Holding’s CFO fly from Riyadh to New York a few weeks before the list came out to ensure that Forbes used his stated numbers. The CFO and a companion said they were not to leave the editor’s office until that commitment was secured. (After a granular discussion the editor convinced them to leave with a promise to review everything.) In 2008, I spent a week with him in Riyadh, at his behest, touring his palaces and airplanes and observing what he told me was $700 million worth of jewels.

Keeping up with Prince Alwaleed, as I learned during my week with him, requires fortitude—and caffeine. He stays up nightly until roughly 4.30 am, before catching 4 or 5 hours of sleep and repeating the drill. “Whoever worked with the prince had no life,” recalls an early former employee. “The working hours were extremely odd: 11 am to 5 pm and then 9 pm to 2 am.” Even his twentysomething wife must ï¬t into this schedule (she’s his fourth bride, though he’s only been married to one at a time) when I was there she would be chauffeured home nightly to her own palace in a midnight-blue Mini Cooper.

The daily surroundings are absurdly opulent. His main palace in Riyadh has 420 rooms, ï¬lled with marble, swimming pools and portraits of himself. If he needs to go on a business trip, he has his own 747, à la Air Force One, except unlike the President, his plane has a throne. If Alwaleed wants a change of pace, he can go to his 120-acre “farm and resort” at the edge of Riyadh, complete with ï¬ve artiï¬cial lakes, a small zoo, a mini-Grand Canyon, five homes, 60 vehicles and several outdoor spots designed for his entourage to take dinner together.

That meal is very important to Alwaleed. To keep trim he eats one main meal a day, at about 8 pm, though given his body schedule he calls it “lunch”. He’s flanked on one side by his entourage of “palace ladies”, who run whichever house he’s in, and on the other side by male attendants. All eyes in the semi-circle are usually centred on a television. And lest anyone forget the prince’s focus, that television is usually tuned to CNBC.

This ambition, albeit in gilded form, was in many ways a birthright. If ever someone carried a burden to succeed, it’s Prince Alwaleed, the grandson of the founding fathers of two separate countries. His maternal grandfather was the ï¬rst prime minister of Lebanon. His paternal grandfather, King Abdulaziz, created Saudi Arabia. “That puts him in a place where he has to prove himself to be ï¬rst at something,” says Saleh Al Fadl, an executive at Saudi Hollandi Bank who worked under Alwaleed for many years beginning in 1989 at the prince’s United Saudi Commercial Bank. While his cousins in the House of Saud responded to similar pressure by ï¬lling Saudi Arabia’s political class—one serves as interior minister, while others serve as governors—Alwaleed, Al Fadl says, “wanted to prove himself in the business area”.

Alwaleed’s father, Prince Talal, had a mind for business, serving as Saudi Arabia’s reform-minded ï¬nance minister in the early 1960s, before he was driven into exile due to his progressive views. During that same period, when Alwaleed was 7, he separated from his wife, the daughter of the original Lebanese prime minister, who returned to her country with the young prince. There he had a habit, according to his authorised biography, of running away for a day or two and sleeping in the back of unlocked cars. Alwaleed wound up attending military school in Riyadh, picking up a strict discipline he adheres to even now.

The prince acquired a Western outlook in college, attending Menlo College in Atherton, California. When he returned to Saudi Arabia, he became known as the guy foreign companies could do business with if they needed a local partner. His standard explanation about how he got started is that he got a $30,000 gift from his father and a $300,000 loan and a house. While it’s unclear, even in his biography, how much else he got from his family, it was presumably a lot, since by the time he was 36, in 1991, he was positioned to make the high-stakes business decision that would deï¬ne him. As regulators pressured Citicorp to increase its capital base in the face of bad loans across developing countries, Alwaleed, then unknown outside Saudi Arabia, amassed a $800 million position. That enormous bet ballooned across two Wall Street boom cycles—by 2005 it was worth $10 billion, making Alwaleed, at the time, one of the 10 richest people in the world, and earning him a nickname, which he encouraged, of “the Buffett of Arabia”.

But unlike Warren Buffett, who has picked winner after winner for decades, Alwaleed has not proven to be a consistent investor. Over the past 20 years he has backed some serious dogs, such as Eastman Kodak and TWA. High-proï¬le media investments (Time Warner and News Corp) turned in middling performances. And while there were also big winners, notably eBay and Apple, Alwaleed missed out on another jackpot when he dumped much of his holdings in the latter in 2005. In other words, Alwaleed has yet to repeat what he pulled off with the Citi investment. “That was his huge deal and what put him on the map. It was a big risk, a big number, a big bank,” an executive formerly close to Alwaleed told Forbes. “Nothing he’s done since has been anywhere near that caliber.”

Nonetheless, in Alwaleed’s hyperbolic world, ambiguity doesn’t translate. Kingdom Holding’s website opens with ï¬ve large, bold words: “The World’s Foremost Value Investor.”

When the prince decided to take Kingdom Holding public in July 2007, the move, on paper, seemed puzzling. While the CFO cites the usual reasons for going public, the prince already owned the company 100 percent. It was ï¬lled with holdings that were already publicly traded, and he floated a measly 5 percent. In other words, he had no partners to satisfy, no liquidity issues and no desire to raise major capital—the three major reasons to do an IPO and accept the headaches that come with a public company.

The shares, listed on the Saudi stock exchange, are thinly traded. No analysts actively follow it. Inside the company the attitude seemed more akin to the vanity magazines his staff produces. “[It was] for the sport of it,” says the early Alwaleed employee. “It’s fun to go public. You have lots of media buzz around it.”

Of course, that media buzz is only “fun” if the stock is performing well. The prince, ever image-conscious, had no doubt it would. “I am very pleased that the IPO continues to go strongly,” he told the Arab News the day the shares were offered. “This indicates that Saudis are recognising the potential of the No. 1 company in the Kingdom.” No matter that oil behemoth Saudi Aramco has pumped the economy full of cash and supported legions of royal family members for decades. “His vision is to be the top-tier wealthiest recognised individual and a public ï¬gure, and this he has achieved,” says Al Fadl of Saudi Hollandi Bank. “Maintaining it would be the toughest challenge.”

That would prove true shortly after the IPO. At the offering, which valued Kingdom at $17 billion, the majority of the company consisted of those Citi shares, worth nearly $9.2 billion. But the summer of 2007 marked the beginning of a long, steep decline, accelerated by the worldwide ï¬nancial crisis. Citi shares have lost 90 percent of their value since July 2007. Kingdom Holding shares tumbled between early 2008 and early 2009, falling 60 percent. That erased $8 billion of the prince’s fortune, knocking his net worth down to a mere $13.3 billion on the 2009 Forbes billionaires list.

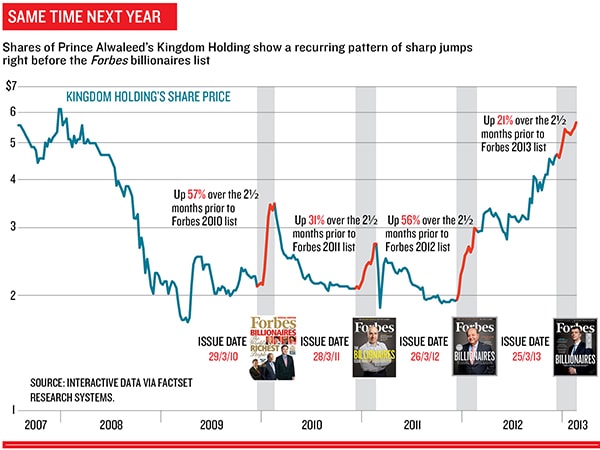

But then Kingdom Holding shares began what seemed a miraculous rebound in early 2010, rising 57 percent in the 10 weeks prior to the February date that Forbes used to lock in values for that year’s Billionaires list, as Citigroup shares fell about 20 percent. The prince’s ranking on the Forbes billionaires list surged in lockstep to 19th ($19.4 billion).

In 2011 the pattern repeated. In the 10 weeks before Forbes locked down its list, Kingdom Holding shares rose 31 percent while the Saudi index was up 3 percent and the S&P 500 was up 9 percent over that same period. (Prince Alwaleed ï¬nished at No. 26 in the world that year, with an estimated net worth of $19.6 billion.) It happened yet again in 2012, when Kingdom shares climbed 56 percent while the Saudi market was up just 11 percent, and the S&P 500 was up 9 percent. (This time Alwaleed was No. 29, with a $18 billion valuation, after Forbes discounted his claims on many of his non-Kingdom Holding assets.)

During this time period several former executives close to Alwaleed began telling Forbes a consistent story: The prince was using his public vehicle to inflate his net worth. Their accounts were based on closely watching the stock, versus direct evidence. But one executive said he could not ï¬gure out any other explanation for why the shares went up dramatically at the same time the key asset, the large Citi stake, tanked.

“This is the national sport,” says an early Alwaleed executive, in offering an explanation for the stock’s wild gyrations. “The players are not many. They come in with big funds, and they buy from each other. There are no casinos. It’s the gambling site of the Saudis.” Says an analyst who follows Saudi Arabia, but requested anonymity because his opinions would erode his relationships: “It’s incredibly easy to manipulate,” and especially easy if, like Kingdom Holding, “you have a small free float.” Responds CFO Sanbar: “No one can rationalise any short-term fluctuations in the share price or the market directions.”

Whatever the driver, this past year has topped them all. In 2012 Kingdom Holding’s net income grew by just 10.5 percent to $188 million, the Saudi index rose 6 percent and the S&P went up 13 percent, yet Kingdom’s shares jumped 136 percent. Sanbar credits “market conï¬dence in the company’s sustained ability to deliver and realise substantial value to its shareholders.” Kingdom Holding now trades at a rich 107 times trailing earnings, not exactly the province of a value investor like the prince. It’s not an unheard-of valuation Amazon trades at 224 times its pre-tax 2012 income. Sanbar also points out that there were numerous other stocks on the Tadawul exchange that were up more than 130 percent in 2012.

The problem with Kingdom is reconciling this share performance with the underlying assets or the fundamentals. One-ï¬fth of Kingdom’s net assets are passive equity investments in stocks that trade at multiples 82 percent below that of the holding company. And there’s scarcely a reason for an investor to buy into the rest, since it’s near impossible to know exactly what the company owns. When the company went public, it issued a detailed 240-page prospectus listing the number of shares owned in 21 stocks, most of which were US ï¬rms like News Corp, Apple and Citi, as well as stakes in various hotels and real estate in Saudi Arabia. But while the prince’s press department issues a release almost daily on who he meets, the annual reports and ï¬nancial statements in recent years failed to provide the names of the stocks or holdings the company currently owns, not even its 7 percent of News Corp voting shares. (We know it owns this because of News Corp’s SEC ï¬lings.)

Concerns about the divide between the price and the underlying assets were raised by Kingdom’s auditor, Ernst & Young. In 2009 and 2010 it signed off on the company’s books but noted in both years a large difference between the market and holding value of the stock. It was such a large difference, the auditor noted, that the prince had to inject 180 million personal shares of Citi, worth perhaps $600 million, at no cost to Kingdom, simply to reduce pressure to mark down assets. In other words, the prince was moving assets he owned privately 100 percent into a public vehicle he owns only 95 percent for no consideration, in order to prop up the books, and presumably the stock. What did Ernst & Young have to say in 2011? Nothing. As of March of that year, it was gone, replaced by PricewaterhouseCoopers at the annual meeting.

Sanbar told Forbes that no shares had been sold since 2008—but we don’t know what shares, if any, might have been sold between July 2007 and the end of 2008. Kingdom did issue a press release in January 2012 stating that it had invested $300 million in Twitter— an investment split between Kingdom Holding and the prince’s personal funds. Sanbar conï¬rmed that stakes in Apple, eBay, PepsiCo, Priceline, Procter & Gamble and a few others had not changed. But as an investor in Kingdom you wouldn’t know that by reading the company’s annual report. A footnote on the 2012 ï¬nancial statements lists unaudited net equity assets of $2.1 billion and one sentence: “The activities of the Equity segment are mainly concentrated in the United States of America and the Middle East.” That minimal amount of disclosure “certainly wouldn’t fly in the US on the grounds of common sense,” says Jack Ciesielski, the publisher of The Analyst’s Accounting Observer newsletter.

Sanbar’s response? “We are not a mutual fund and there is no requirement whatsoever that we disclose to anyone the share make-up of our portfolio.”

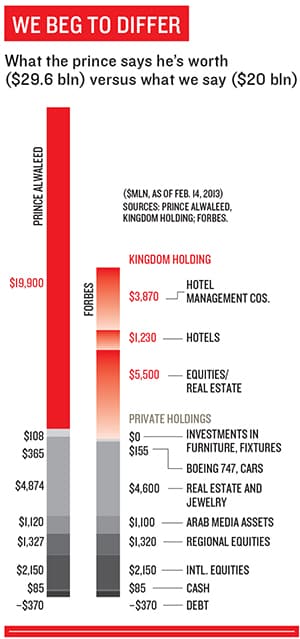

While public companies are almost always a market-proven determinant of net worth, in light of Kingdom’s opacity, small float and thin, questionable trading, Forbes decided to focus on the underlying assets. We estimated the earnings from its stakes in the Four Seasons, Mövenpick and Fairmont Raffles hotel management companies and, working with a hotel-industry investment banker, applied a generous public-company multiple. We also came up with a value, net of debt, for the stakes in more than 15 hotels owned by Kingdom.

Based on the other parts we can identify, including Saudi real estate and a basket of US and Middle East equities, we value his Kingdom Holding stake at $10.6 billion, or $9.3 billion less than what the market cap suggests.

Even crediting the prince with most of the $9.7 billion of assets he claims outside of Kingdom—Sanbar listed $4.6 billion of appraised Saudi real estate $1.1 billion in Arab media companies (which Forbes discounted because the prince uses a net present value of future proï¬ts, while we use a multiple of current earnings) and a nonspeciï¬c $3.5 billion of investments in public and private companies globally—and even including various planes, yachts, cars and jewels, Forbes cannot justify an estimate of more than $20 billion. Still the richest man in the Arab world. Still $2 billion over last year. But $9.6 billion less than what the prince insists. And while Forbes prides itself on conservative estimates, in this case, we believe the proceeds in a wind-down would, if anything, be less.

A week before Forbes ï¬nished its tabulations, the prince directly charged his CFO with making sure the 2013 Forbes listing would be to his liking: Speciï¬cally $29.6 billion, which would return him to the top 10 position he has craved. The direct order to Sanbar, according to someone outside the company who is privy to the prince’s thinking and speciï¬c language on this matter, was to get “nasty”.

What followed were four detailed letters from Sanbar attacking our reporters and our methodology for unfairly singling out the prince for scrutiny. “Why does Forbes apply different standards to different billionaires, does that depend on national origin?” Sanbar wondered.

In one letter Sanbar insisted that Kingdom’s holdings have soared in value, without offering detail. He did mention that Kingdom has reduced unrealised portfolio losses by almost $1 billion since 2008. In another letter he says that Kingdom’s 2007 IPO was scrutinised for 12 months by the Saudi Capital Market Authority. “This strikes in the face of improving Saudi-American bilateral relations and co-operation. Forbes is putting down the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia and that is a slap in the face of modernity and progress.”

Finally, Sanbar insisted that Alwaleed’s name be removed from the Billionaires list if Forbes didn’t increase its valuation of the prince. As Forbes asked increasingly speciï¬c questions in the process of fact-checking this story, the prince acted unilaterally the day before it was published, announcing through his office that he would “sever ties” with the Forbes billionaires list. “Prince Alwaleed has taken this step as he felt he could no longer participate in a process which resulted in the use of incorrect data and seemed designed to disadvantage Middle Eastern investors and institutions.”

“We have worked very openly with the Forbes team over the years and have on multiple occasions pointed out problems with their methodology that need correction,” Sanbar said in the statement. “However, after several years of our efforts to correct mistakes falling on deaf ears, we have decided that Forbes has no intention of improving the accuracy of their valuation of our holdings and we have made the decision to move on.” And how did Prince Alwaleed convey this message? By press release.

First Published: Mar 28, 2013, 07:27

Subscribe Now