Tara books: Love notes to tribal art

Welcome to the world of Tara Books, where each page is a love note to tribal art

Bhajju Shyam was only 30 when he lost his “guru”—his uncle Jangarh Shyam—to crippling depression in 2001. Then India’s leading tribal artist, Jangarh committed suicide while in Japan on work. He was just 39. This was no ordinary loss. Bhajju had lost the man who had mentored him since he had arrived in Bhopal as a 16-year-old boy in search of work. It was his uncle who had recognised the spark in him which, today, has become a flame. And its glow is palpable from the minute you enter Book Building, which is home to independent publishing house Tara Books in South Chennai.

A small but airy bookshop and an exhibition space occupy the ground floor, showcasing the many-hued heroes of the establishment. Many of these are entirely handcrafted—from the illustrations and printing to the binding. Take a closer look and you could even call them love notes to Indian tribal art.

Beyond the exhibition space is an open courtyard. A large, grey tree with colourful birds perched on its branches is painted across one of its walls.

C Manivannan, the sales manager, calls its creator “one of the best Gond artists alive”.

The mantle seems to have transferred seamlessly from uncle to nephew.

“I made a barren tamarind tree on a wall at Book Building for its inauguration a few years ago,” Shyam, 44, tells ForbesLife India on the phone from Bhopal. “I wanted to say that now it [the building] is new, but little by little, people will come in and fill it up, just like the leaves will sprout on the tree and birds will come and sit on it. Every time I go back, I try to add a little bit more to it.”

It is an uncomplicated philosophy, one which is manifest in some of Tara Books’s best-known works. Take Shyam’s first-ever creation.

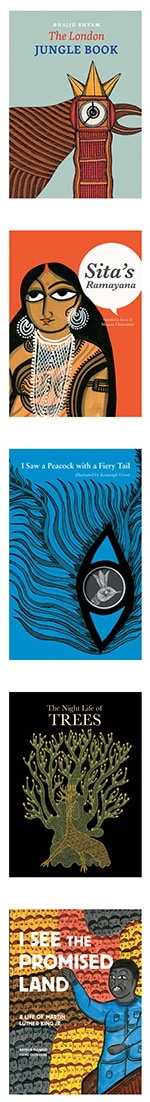

Near the staircase to the upper floor, a small sign printed on paper and stuck on the wall tells visitors that entry is restricted. This is where we first meet the original print of The London Jungle Book. The book is a travelogue of Shyam’s first trip to London it features the illustrative interpretations of his surroundings in his native Gond art tradition, along with an English translation of his experiences.

The illustration of Big Ben imagined as a rooster (as depicted on the cover) is explained as: “I saw Big Ben, and I thought: So this is their temple of time. It’s beautiful, and carefully built because they are very careful about time here. If you are five minutes early for an appointment, they will tell you to wait because you are early. If you are five minutes late, they will tell you that you are late. Everyone checks their watches all the time. I have a watch too, but my symbol of time is still the Gond one—a rooster. It wakes you up at sunrise. Then the day follows its course, and the next event that marks the passage of time is the sun going down.”

Gita Wolf, 58, founder of Tara Books, articulates her original aim for the organisation as “to get stories from people that you never hear from, to hear it from their point of view”. Even in his first effort, Shyam stayed true to the brief.

“Many of the tribal artists that we work with would sell their prints in order to make a living, but we helped them become authors,” says Wolf. They could be the Patuas of Bengal, the Meenas of Rajasthan, the Gonds of Madhya Pradesh or the Mithilas of Bihar among others. This is considered unparalleled in the Indian independent publishing industry. “Tara Books has pioneered the use of tribal art in books to provide a modern relevance to it,” says Anita Roy, director and senior editor at the Delhi-based independent publishing house Zubaan Books. Roy believes that Tara Books has “taken tribal art out of its museum box and given it a contemporary feel and relevance”. “I think their philosophy can be summed up in two of their books: The London Jungle Book and That’s How I See Things, both by Bhajju Shyam,” says Roy. That’s How I See Things is a humorous story of an artist who sees the world differently. “Both these books, especially The London Jungle Book, showed people that western modernism wasn’t the only way to look at the world.”

All this in just over two decades: Tara Books was founded in 1994 by Wolf along with five co-founders—all six are listed as owners though she likes to believe the ownership vests with the larger community of writers, artists and designers. And as the army of collaborators has grown, so has the publishing house’s repertoire: What began with picture books for children has now expanded to include novels such as The To-let House by Daisy Hasan, which was long-listed for the Man Asian Literary Prize. However, it’s the hand-made visual books, with stories told and illustrated by tribal artists, which hold pride of place.

In the bookshop, close to where Manivannan sits, it catches my eye. A large black book, with a kind of deer standing in front of a tree featured on its cover. Titled The Night Life of Trees, it has been illustrated and written on pitch-black pages and it looks to answer one simple question: What happens in the forest after darkness falls? Created by three Gond artists—Ram Singh Urveti, Durga Bai and Bhajju Shyam—the trees featured are considered sacred by the Gonds due to their importance to human sustenance. This collaboration was of Shyam’s making. “They had stories,” he says of his co-creators, “more than even I did.”

Like Shyam, many of the artists stay in Chennai as part of Tara Books’s residency programme. Book Building’s top floor has a two-bedroom apartment that serves as a home for resident writers, artists or designers for varying periods of time. One such collaborator was Jonathan Yamakami, a graphic designer from São Paulo, Brazil, who worked on two books during his time at Tara Books.

I found myself in a staring contest with the peacock on the cover of his I Saw a Peacock with a Fiery Tail. “Ram Singh [Gond artist] had the ingenious idea of alternating black and white backgrounds for the book,” says Yamakami, whose job was to marry the art with the text and visualise the final product. The book is an illustrative interpretation of a 17th century English ‘trick poem’ by Ram Singh Urveti.  Pioneering change: The tamarind tree painted by Bhajju Shyam on a wall at Book Building

Pioneering change: The tamarind tree painted by Bhajju Shyam on a wall at Book Building

The lead character of Yamakami’s other book is well known. “I started working on Sita’s Ramayana almost immediately after I moved to India,” says Yamakami, who worked with Tara Books from 2009 to 2011. The book is written by Bangalore-based writer Samhita Arni and illustrated by Moyna Chitrakar, a Patua artist. “Moyna and Samhita’s Ramayana is very different from the abridged version that I had read,” he says. Reason: It puts Sita centre stage. “In the end, she will decide her own path,” Yamakami points out. Sita’s Ramayana was on the seventh spot on The New York Times Bestseller list for graphic novels for two weeks in 2011. “[In Sita’s Ramayana] Moyna’s work was vibrant and colourful, emerging from a narrative she was very familiar with,” says Yamakami. “Ram Singh [in …Fiery Tail] was responding to an English poem from the 17th century, something alien to him.”

This is also a pointer to the individuality in their processes—as it is with their styles. The Gonds, like many other tribal artists, originally began by painting their huts and floors and later moved to canvas and paper. The Patuas were traditionally itinerant storytellers who would narrate their stories with songs while displaying images on vertical scrolls. In fact, as V Geetha, editorial director at Tara Books, writes in the publisher’s blog, “On the back of each panel [in Sita’s Ramayana], Moyna had pencilled in, in Bangla, her description of the scene, clearly a paraphrase of the song she would have sung had this been a scroll.”

This variance in approach is evident—even celebrated. “When we meet other artists, say, like the Patuas, we talk about our folk tales and discuss the stories,” says Shyam. “We’re all very different from each other.” Wolf agrees. “Even within the same tradition, the artists are all proud individuals,” she says, “with a strong sense of identity.” This is why one must be wary of using umbrella terms like tribal art to define a whole spectrum of traditions and art forms, she says. “It is really the pride that they have in their traditions that makes them work hard to preserve them.”

We were soon to witness a little bit of that effort.

A 10-minute drive from Book Building brings us to the Tara Books workshop, which is a small house in a residential colony. We are warmly greeted by a genial man, Manikandan, who leads us inside—this is where the ‘magic’ happens. Although, magic has little to do with it. Hand-made books—the most distinctive aspect of Tara Books—re quire a time-consuming process. “They are printed and bound by a team of 23 people,” says Manikandan, 38, who is head of printing and has worked at the workshop since it began production 19 years ago. “I came here after finishing class 12,” he says.

The 23 staffers hail from villages surrounding Chennai and live in accommodation provided by Tara Books. “Everyone is trained to do both printing and binding,” says Manikandan. They are currently binding pages of a book titled Creation. It is another Bhajju Shyam collaboration with Tara Books, and dwells on the myths of origin and the ending of the cosmos according to Gond folklore, through exquisite illustrations and an accompanying textual narrative. Creation, which has been translated into four languages, is currently being printed in Japanese.

The simplicity of the screen-printing process belies the expertise required to create these books, particularly with the kind of consistency and speed that Tara Books achieves. By its own estimates, 25,000 copies are published every year. “We work from 9 am to 6 pm,” says Manikandan. It isn’t all work, though. They also spend their downtime together. “In fact, we’re all planning to either go to the beach or watch a movie this weekend,” he grins.

What helps is a real passion for the work they do. Manikandan points to one of his personal favourites, Waterlife, on display at the workshop. It has vibrant illustrations of sea creatures by Rambharos Jha, a Mithila artist from Madhubani in Bihar.

Jha has only seen many of these creatures in pictures, but you couldn’t tell that from the intricacy in his paintings. Bulgarian writer and blogger Maria Popova, in her review of the book on her blog, BrainPickings.org, goes so far as to write, “(Waterlife) is, without a shadow of exaggeration, the most beautiful book I’ve ever laid my eyes on.”

Though most of the artists don’t live in Chennai, they “often visit us at the workshop,” says Manikandan. “Bhajju Shyam’s been coming here for many years now.” What’s odd is that while he speaks Tamil and a little bit of English, Bhajju speaks Hindi. How, then, do they converse? “I try a little Hindi,” he smiles. “But he understands me, yes.”

And he doesn’t need words. The lines speak, and they use a beautiful language, exotic to Indians and foreigners alike.  The screen-printing process underway at the workshop

The screen-printing process underway at the workshop

Emmanuelle Loeve, a graduate student at The School of Oriental and African Studies in London, calls Tara Books’s approach “interesting in that not only does it popularise tribal art but it also allows you to acquire a ‘unique’ work of art with the hand-made books”. “You could almost frame the book,” she says. However, Loeve finds that in the case of The London Jungle Book, Tara may be guilty of “fostering this vision of the naive tribal artist discovering modernity”.

Tara Books offers a different view. In the epilogue of The London Jungle Book, Wolf and Shirish Rao, who have both helped translate the book, write that “the book manages to reverse the anthropological gaze”, which is a stated aim of Tara Books. (They also mention the ironical connection with Rudyard Kipling’s work as the source of the title.)

But there’s no escaping the fact that the motley collection of artists, designers and writers throws up a language conundrum. And the books that come out must face this challenge before all else. Philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein, in his book Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus, wrote: “The limits of my language mean the limits of my world.” Bhajju Shyam experienced this when he visited London for the first time in 2002 to paint the walls of the upmarket Masala Zone restaurant in Islington. “I felt like my language had been taken away from me,” says Shyam. “I would be able to tell them so much more if only I spoke their language.” And although it has been 13 years since, Shyam’s feud with language continues.

In that context, for him, and others like him, the bridge provided by Tara Books is invaluable. Tara Books publishes about 10 titles a year and continues to experiment. “Right now, we’re bringing out a book entirely made of textile,” says Wolf. Ask her about the business, and she points to the fact that publishing is rarely highly profitable. “Let’s just say we make enough to put money into other books. We’re surviving.”

More importantly, they are helping tribal arts survive, and you can’t put a price on that.

First Published: Jul 31, 2015, 06:53

Subscribe Now(This story appears in the Jul 16, 2010 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, Click here.)