Saving India's cinema, one film at a time

Restorers are trying to preserve what's left of India's film legacy, but is it too late?

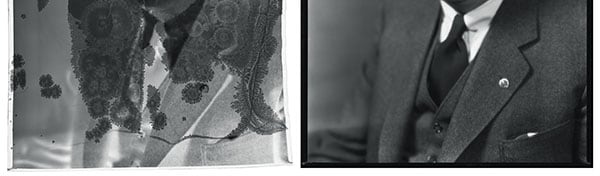

Lost forever: The restored look of a scene (above) from a spoilt film (as shown left)

Lost forever: The restored look of a scene (above) from a spoilt film (as shown left)

There are films we will never see. Actors and actresses we will never know. It is a loss that haunts PK Nair, India’s most-renowned archivist, every day. In the 1960s, the ministry of information and broadcasting gave him Rs 25,000 to start an independent body that would archive Indian films. At the time, he was working at the Film and Television Institute of India (FTII), Pune, collecting films for students. Spurred by his love for cinema, Nair scoured studios and directors’ homes for old and neglected movie reels, especially those from the silent era. Twenty-five thousand rupees, however, were not enough for this mammoth task, and he often had to ask officials for more funding. “I remember one government employee asking me, ‘Why should public money be used to save some junk when we don’t have money for electricity and basic amenities?’,” says Nair, who founded the National Film Archive of India (NFAI), Pune, in 1964.

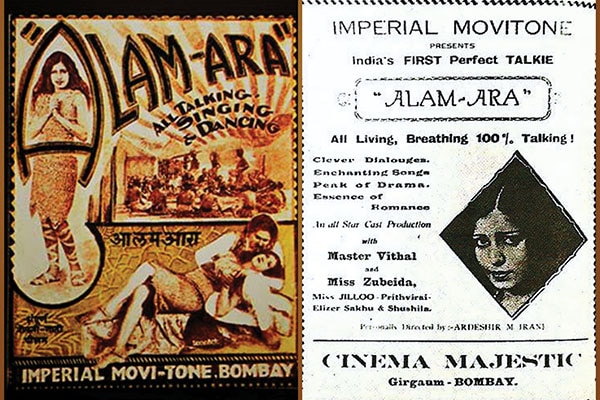

Director Shivendra Singh Dungarpur chronicled 81-year-old Nair’s contribution to Indian cinema in his 2012 National Award-winning documentary, Celluloid Man, but its making, he tells ForbesLife India, was a grim reminder of the cavalier attitude towards our century-old cinematic legacy. At least 70 to 80 percent of the films made in India before 1950 are lost forever. The original reels are either missing or destroyed beyond repair. Of the 1,600 titles that date back to the silent era from 1899 to 1931, less than ten remain intact. Only portions of one of India’s earliest films, Dadasaheb Phalke’s Raja Harishchandra (1913), have been preserved because of Nair’s efforts. India’s first talkie, Alam Ara (1931), can never be retrieved as the nitrate negatives were sold for silver. India’s first talkie Alam Ara (1931) can never be retrieved as the nitrate negatives were sold for silver

India’s first talkie Alam Ara (1931) can never be retrieved as the nitrate negatives were sold for silver

This scale of destruction can be blamed on the short-sightedness of studios and even accidents. For one, film stock is a perishable item, easily susceptible to damage, and nitrate negatives are highly inflammable. Reels, which were stored in poorly ventilated rooms or vaults, wilted in the humidity. Many were destroyed in studio fires.

The toll would have been higher had it not been for Nair who dedicated more than 25 years of his life to the NFAI. By the time he retired in 1991, he had hunted down, rescued and archived 12,000 films, including classics made by auteurs such as Dadasaheb Phalke (1870-1944), Satyajit Ray (1921-1992), Raj Kapoor (1924-1988) and Guru Dutt (1925-1964).

Before the NFAI got its own premises in Pune, Nair and his team stored old reels in different studios. “One of them was Prabhat Studio in FTII. The steel vaults were so heavy that we needed two people to open them. The rooms had no air-conditioning. Instead, they had double walls with pebbles in between, and a water tank on the roof, to keep them cool,” says Nair. Today, the NFAI has its own temperature-controlled vaults where nitrate reels of rare black-and-white films are stored and preserved.

Film historian, scholar and author Amrit Gangar believes that the culture of preservation came into existence a few decades too late to save early classics. “Before the 1960s and the NFAI, production studios stored the negatives and positives of films themselves. Once the films were released and money recovered, or even lost, they showed no interest in keeping the negatives. They chose not to invest huge amounts in the scientific preservation of their productions,” says Gangar.

The loss is felt all the more today, and is one of the main reasons why film lovers and experts like Dungarpur, and organisations such as the NFAI and the National Film Development Corporation (NFDC), are scrambling to restore those reels that can be saved. It is a time-consuming (can take six months to more than a year depending on the damage) and expensive (average cost is Rs 15 lakh) task.

Last year, Dungarpur started the Film Heritage Foundation, a non-profit organisation in Mumbai, dedicated to the acquisition and documentation of all film-related material. This includes original posters, scripts and songbooks. “I always say that the only way to move ahead is to look back. Unfortunately, we Indians don’t have a culture of preservation. There is a general lack of understanding about the matter,” says Dungarpur. “In a funny way, the shopkeepers at Mumbai’s Chor Bazaar (a flea market) who sell old film posters are actually helping in preserving them.”

The foundation’s most ambitious project is the Film Preservation & Restoration School, which runs seminars, workshops and educational programmes. In February 2015, it tied up with Martin Scorsese’s The Film Foundation for a week-long workshop, with practical and theoretical classes on restoration and archiving.

Andrea Kalas, vice-president of archives at Paramount Pictures, who was in Mumbai to give a lecture at the workshop, says restoring and preserving a film requires an understanding of the director’s vision. She was instrumental in releasing the Hollywood film Sunset Boulevard (1950) in Blu-Ray in 2012. When working on a print that is so badly damaged, restorers often have to change the colour of an object or tweak the background sound if is unclear. It is important that in making these changes, the director’s original intent is not lost. “We spent months researching on how Sunset Boulevard was filmed and the vision its makers had so that we could reproduce it accurately,” says Kalas.

Hollywood, too, is guilty of losing thousands of old silent films to neglect, decay and apathy. A survey conducted by the Library of Congress found that nearly 80,000 titles or 70 percent of the movies made in the US between 1912 and 1929 are lost. Today, however, there is a robust restoration and preservation sensibility.

Digital remastering of old films is underway in India, too. Over the last three years, the NFDC has restored 87 classics and digitised another 31 titles. The oldest it has saved is Rabindranath Tagore’s Natir Puja, a Bengali ‘talkie’ made in 1932. Three years ago, the NFDC, which also finances and produces films, released a digitally remastered version of its 1983 cult film, Jaane Bhi Do Yaaro, starring Naseeruddin Shah. At the time, director Kundan Shah said he had found his 30-year-old film’s negatives in tatters, rotting in the musty vaults at NFDC, which has its headquarters in Mumbai and regional offices across the country.

Treasure trove of Indian cinema: (Clockwise from extreme left, bottom) MS Sathyu’s Garm Hawa, which was re-released in 2014 a still from Devdas a poster of Jaane Bhi Do Yaaro and actors Bharat Bhushan and Anita Guha during a film shoot at Ranjit Studios in Mumbai

Treasure trove of Indian cinema: (Clockwise from extreme left, bottom) MS Sathyu’s Garm Hawa, which was re-released in 2014 a still from Devdas a poster of Jaane Bhi Do Yaaro and actors Bharat Bhushan and Anita Guha during a film shoot at Ranjit Studios in Mumbai

NFDC’s deputy general manager, D Ramakrishnan, who oversees the restoration work from the Chennai office, says on an average, technical experts can take anywhere between two and six months to work on a film. “Most of the original picture and sound negatives have deteriorated over time. We find dirt, scratches and tears and colour fading in the source negatives,” says Ramakrishnan. His biggest challenge has been Satyajit Ray’s Bengali film Jalsaghar (1958). “The negatives of the film didn’t exist. The restoration was done from a positive print. There was dust, bumps, continuous line scratches, mould, patches and flickering in the source print.”

In November 2014, MS Sathyu’s Garm Hawa (1974)—a Hindi-Urdu film set after Partition—was re-released in theatres by PVR Cinemas. The film was given a substantial overhaul and the sound was converted from mono to surround. It took a team of experts, including Sathyu, three years and almost Rs 1 crore to restore Garm Hawa for the large screen.

Initiatives such as these prove that damage-control measures are underway. “Courses like the one established by the Film Heritage Foundation should be welcomed. Even though we have lost most of our silent and early talkie films, we need to make our younger generation aware of the significance of preserving our film heritage,” says Gangar.

A restorer’s and an archivist’s task will never end, not as long as films are being made, and there is a sense of urgency among the old guard to pass on the information to the next generation of ‘cinephiles’. “I am afraid the moving image (audio-visual) used now is much more fragile. The digital film has its own problems. Restoration is a complex process that requires immense patience and perseverance, but is particularly important in this age of restlessness and shortcuts,” Gangar adds.

It takes a special kind of zeal, dedication and foresight to preserve art. Gangar remembers a visit to East Germany in 1989 before the fall of the Berlin Wall. “I had travelled to East Berlin where I met some officials who were in charge of preserving films. They told me that they were converting trenches created during WWII into proper storage sites to preserve film prints,” he says. Early this year, he visited The Cinémathèque Française in Paris, which holds the world’s largest archives of films, movie documents and film-related objects. And much like the NFAI’s ties to Nair, the archives owe their existence to one man, archivist Henri Langlois, who went through unimaginable lengths during WWII to hoard film reels that were in danger of being destroyed under the Nazi regime. When he founded The Cinémathèque Française in 1936, it was a small enterprise meant to preserve and exhibit films. Today, it is one the most exhaustive repositories of cinema world over and a testament to what extraordinary passion for cinema can drive a single person to do.

Nair, too, may have started out as a lone warrior, but he has paved the way for generations of archivists who are not only saving the past, but also preserving the present.

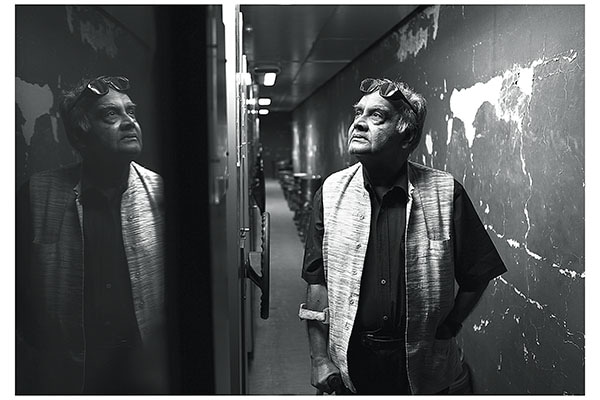

Film archivist PK Nair on his hunt for rare, old Indian movies

By PK NairRestoring glory: PK Nair, India’s most-renowned film archivist

When I started the National Film Archive of India in the 1960s, it was initially meant only to keep copies of films that had won gold and silver medals at the National Awards. But before the talkies, we had made approximately 1,600 silent films of which we had no record. I started by looking for Dadasaheb Phalke’s work. I remember getting the first reel of Raja Harishchandra from Phalke’s daughter, Mandakini. After two years, I met Phalke’s son, who was staying in Dombivli, Mumbai. He gave me another reel. At the time, I didn’t know that this would turn out to be the last reel of the film. They were all in bits and pieces and needed to be joined to make them into a film. These early silent films were not very long. The duration of most of them was between 10 and 20 minutes. It was only in late ’20s that our films started becoming two hours long.

I kept hoping that the other reels of Raja Harishchandra would ‘turn up’. I went to Phalke’s home in Nashik, where all his things were dumped in a trunk. I went through all that was there, but couldn’t find the remaining portions. But I found bits of his other films—sometimes just half a reel.

I managed to collect only nine to 10 silent films. That’s all we have in our archives from that era. Finding them was like going on a wild goose chase. I got some from Kolhapur, a few from Pune, and a Malayalam film from Kerala.

Films need constant attention. The movies being made today are easy to handle because they come in a disc and don’t take up too much space. Earlier we had to look after 15 reels of picture and 15 reels of sound for each film. But there are a lot of issues with digital prints too. For example, if there was a problem in the seventh reel of a film, I could work just on that reel and fix it. Now with a CD, one will have to watch the entire film to locate the problem. This is far more time consuming.

Production companies have their own vaults to store films, but producing films and taking care of them are two different jobs. The attitude of someone who is storing films because it will make money for them some day is different from that of a person who is preserving them because it is a part of our heritage. What is lacking in our country is the right attitude to film preservation, but hopefully this will change. (As told to Mohini Chaudhuri)

First Published: Jun 20, 2015, 06:22

Subscribe Now(This story appears in the Jun 18, 2010 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, Click here.)