Why Realty Did Not Bite Piramal

Deploying Rs 12,000 crore in a slowing real estate market is no easy task. Under the leadership of Khushru Jijina, Piramal Fund Management may have cracked the code

When Khushru Jijina, 49, took over the reins at Piramal Fund Management (known as Indiareit Fund Advisors Pvt Ltd till May this year) in 2012, one of his first moves was to stop raising money for the Mumbai Redevelopment Fund. On the face of it, his decision was confusing, perhaps even flawed. Mumbai, with its teeming slums, had large tracts of land that could be cleared for housing. And with the Piramal brand name attached to the fund, there was no shortage of investors. Given all that, why did he stop raising money, we ask him.

Because these were not conventional realty projects, Jijina tells Forbes India, pointing out that a redevelopment project can get stalled due to a number of factors. For instance, the slum land may not get cleared for development. Or slum-dwellers, with the help of political backing, could halt work on an under-construction project. The risk was higher and this needed to be communicated to the investors. “This fund was not meant for someone who is nearing retirement given that we are underwriting redevelopment risk,” says Jijina, who returned those investors their money and made a fresh start at building the fund.

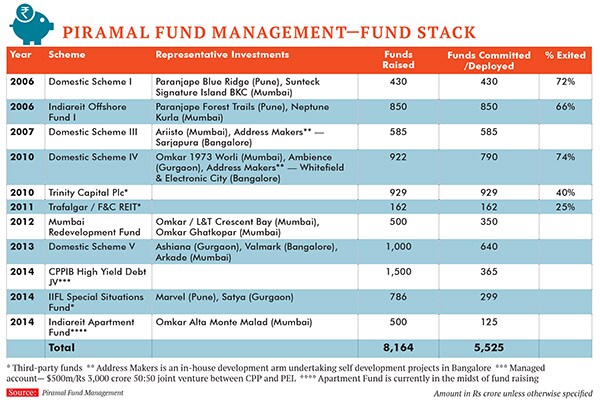

The Mumbai Redevelopment Fund was set up a couple of months before Jijina took over in September 2012 and was in active fundraising mode when he assumed charge. And, by December 2012, it did raise its target of Rs 500 crore—despite the change in course. Only this time, the investor profile was right. Earlier, many people who were nearing retirement had put in money. Now, pension funds and family offices comprise the investor base—these are entities that can take on more risk.This is the kind of smart thinking that has catapulted Piramal Fund Management—set up in 2006—to the upper echelons of the realty fund business. Its name is now mentioned in the same breath as HDFC, Kotak and Red Fort, three other companies that have managed to carve out a profitable niche for themselves. Putting it in context, consider that over 90 percent of the 160 realty funds that set up shop since 2006 have gone belly up. Marquee names such as ICICI were unable to even return the principal amounts to their investors.

So what has worked for Piramal Fund Management? That it is the only player in the industry that focuses on all aspects of the value chain. “Theirs is an interesting model,” says Shobhit Aggarwal, managing director (capital markets) at real estate services firm Jones Lang LaSalle. “It provides growth capital in a variety of forms to promising, upcoming developers—something they would find hard to raise from banks.”

For instance, if a developer wants equity finance, Piramal Fund Management takes a stake in the project. It also provides debt financing at predetermined coupon rates. Then, through a non-banking finance company arm, it offers construction finance.

A recent addition to its services is an apartment fund that buys under-construction apartments from developers who can later sell these at rates, and to buyers, that are controlled by it. Piramal Fund Management also owns a development arm, The Address Makers, which has established three properties in Bangalore.

Given the scope of its services, while all realty funds have a takeover clause in their contracts, Piramal Fund Management has the actual capability to do so if a developer reneges on his commitment. Take, for instance, the fact that no other fund offers construction finance or has funds for specific situations like the apartment fund or the Mumbai Redevelopment Fund.

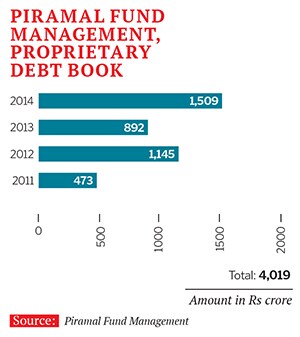

As a result, Piramal Fund Management has Rs 12,000 crore to invest in real estate across the country. It helps that Piramal Enterprises is flush with funds and has over Rs 4,000 crore of investment riding on the venture.

His backing has helped seal marquee deals like a $500 million (Rs 3,000 crore) commitment Piramal Fund Management signed last January with the Canadian Pension Plan to invest in the residential space—this is likely to take place in large metros. According to Andrea Orlandi, head of real estate investments at the Canadian Pension Plan, it had considered over 20 partners in the Indian market. “But it was an alignment of Piramal’s long-term vision with ours that made us sign the deal,” says Orlandi. Pension funds typically invest with a decade-long time horizon.

A large part of Piramal Fund Management’s success, though, can also be attributed to Jijina’s wealth of experience as a finance manager which has manifested in a fresh approach to running the real estate fund.

Unlike his predecessor Ramesh Jogani, Jijina doesn’t have any background in the private equity business. That, he says, helps him assess the job with a different perspective. Before joining Ajay Piramal, Jijina had worked for two decades in the treasury department of agricultural products company Rallis. In 2001, he parlayed this experience into running treasury operations for Piramal.

After he proved instrumental in securing debt at the lowest cost for the Piramal group, he became managing director at Piramal Realty where he spearheaded the group’s interest in the real estate business. This experience provided him with a sound understanding of how the real estate business works. (It is at present run by Piramal’s son Anand while Jijina reports directly to Ajay Piramal.)

After he transitioned to Piramal Fund Management, he started to fix a few niggles.

He saw that the rapid growth—it had raised five funds and was at Rs 4,000 crore at the time—enjoyed by the fund had also come at a cost. Since bonuses were aligned to how a particular fund fared, the individual manager would want to keep the best deals for himself. This created an unhealthy competition among the teams. Jijina decided to tie bonuses to how all the funds performed, thereby aligning the fortunes of the fund managers.

He also realigned the incentive structure. “Industry players were more bothered about the two percent management fees than the 20 percent share of profit that they are entitled to,” he says. Once money was raised, people seemed to lose sight of the fact that they needed to make a profit on it as well. Jijina ensured the focus shifted to profit-making.

“Real estate is a very locally nuanced business and therefore it is imperative to have people on the ground—the telltale signs of a developer’s default are visible much before the actual default,” he says.

This is particularly relevant since, as Jijina points out, work doesn’t end once the money is lent. It is important to track the investment, he says, because, for instance, the telltale signs of a default with a developer start to show far before the actual non-payment issue crops up. For instance, if cement is being diverted from one project to another, Jijina expects his employees on the ground to communicate that fact. Or if a developer is not honouring his commitments to suppliers, that must be reported back too.

In addition, there are some stressed assets from the time the first fund was raised in 2006. These relate to investments in Hyderabad where real estate prices have been stagnant since the creation of a separate state of Telangana gathered heat in the region. Jijina has communicated a plan to investors and says that the return of the principal amount to the investors will be prioritised.

Piramal Fund Management now has a robust number of developers on its client list, including some with whom it has dealt with on multiple occasions. The result: A solid pipeline of projects is now available for review. In 2014, 75 projects were reviewed and 13 approved. Because these relationships tend to be long term, they also allow the fund to get better deals out of their partners. On one project Jijina declined to name, he lent money at 24 percent with a 7 percent extra kicker if the project does well. These rates are at the higher end in the industry.

But it is in the project selection stage that Jijina showed he was a measured manager. And this has held the fund together in a slowing real estate market. His philosophy is simple: It is better to walk away from deals if one is not sure about them.

When approached to finance a slum redevelopment project in Powai, Jijina asked the developer to do some work and only then would the fund consider committing money to the project. “Any other fund would have entered the project at the initial stage of development. With Piramal fund, it wanted us to do some work before the fund could commit,” says Babulal Varma, managing director of Omkar Realtors, the developer behind the project.

As a relative outsider to the real estate industry, Jijina isn’t bogged down by a conventional lens. He does not view the sector like a developer would. His approach, instead, is more akin to that of a banker. He monitors the progress of the project at every stage, in terms of both execution as well as return on investment. “His background is finance. So he looks at everything with a return perspective. More importantly, he wants a developer to show some progress before he gets into the game completely,” adds Varma.

And Jijina is in no hurry either. He believes there is enough work in metropolitan India to keep the fund active, without having to take unnecessary risks. Already present in Delhi, Mumbai, Bangalore and Chennai, Piramal Fund Management plans to enter the Pune market soon. Smaller towns in India are not on the fund’s radar as of now. The promoter is convinced about the efficacy of the model. “We have laid the foundations for a uniquely integrated financing platform thereby positioning ourselves to gain valuable skills and insights—all of which greatly enhance our ability to forge lasting relationships with both our investors and development partners,” says Ajay Piramal, the Piramal group chairman, who has even visited some of the slum redevelopment sites where the fund has invested.

Jijina’s future plans involve a focus on raising money from institutional investors—or “smart money”, as he terms it. This includes family offices and pension and endowment funds. Under him, the approach is also more patient with a willingness to wait for 5-7 years for returns.

Recently, Piramal Fund Management received an exclusive mandate to manage Rs 350 crore raised by India Infoline. Karan Bhagat, managing director of India Infoline Wealth Management, says, “Not only does the team bring to the table real estate expertise, but also extremely strong relationships and constantly evolving investment ideas optimising returns.”

Jijina, clearly, has done little wrong. And his freshness has been the difference. Now, as the “rookie” becomes a “veteran”, he will have to safeguard that his approach, at least, does not get jaded.

First Published: Nov 18, 2014, 06:34

Subscribe Now