The sound of Saavn

India's first music streaming service succeeded in cultivating a large, dedicated user base in a virgin Indian market. But now it has company and the sustainability of its ad-based revenue model is st

In late 2008, when Paramdeep Singh and Vinodh Bhat, co-founders of Saavn, a music company, arrived at the Apple headquarters in Cupertino, California, they were in for some good news.

The technology giant’s music division had invited the duo because Saavn had just become the best-selling label in the world music category on iTunes—Apple’s online media library for music and videos.

The company had ventured into music distribution only in 2007, and had charted a steep learning curve in the first two years. Its founders had to convince hesitant Indian record labels to digitise their music, compile the metadata—the information embedded within an audio file that is used to identify it—and most importantly, develop trust in a market that viewed all digital music dissemination as piracy. The news from Apple then, should have felt like a validation of these efforts. But Singh and Bhat were frustrated.

“We were barely scratching the surface of the [digital media] market,” recalls Singh. In the meeting that ensued, they suggested a number of changes to Apple’s executives. “The price point [at 99 cents a song] was too high, we also told them that they needed to create a Bollywood category and that iTunes lacked phonetic search features.” Unless users spelled the song they were looking for in exactly the same way that it was spelt on the iTunes database, they would not be able to find it, he explains. Despite their initial meeting, and a few subsequent ones along similar lines, “they never really came around,” says Singh.

So, in 2009, they decided to create an online consumer service that would bring music directly to customers, which was a departure from their hitherto business to business (B2B) approach, where they would buy the rights to music and distribute them across the internet to Amazon, iTunes, eMusic and others. However, Saavn was then a joint venture between 212 Media—of which Bhat, now 40, and Singh, now 34, were a part—and the Indian digital entertainment company Hungama Digital. The decision to become a consumer-facing company led to a disagreement with Hungama and the two firms parted ways.

Hungama kept all the B2B relationships in North America (they launched their music steaming app in 2013), while Singh and Bhat retained Saavn, running it out of their offices in New York. By now, Saavn’s third co-founder, Rishi Malhotra, now 39, had also joined the company as president and chief operating officer (COO). “Rishi was a rising star at HBO,” says Bhat of Malhotra, who was VP, multi-platform programme marketing, at HBO. “We spent a lot of time exposing him to what we were doing and he finally decided to join us.”

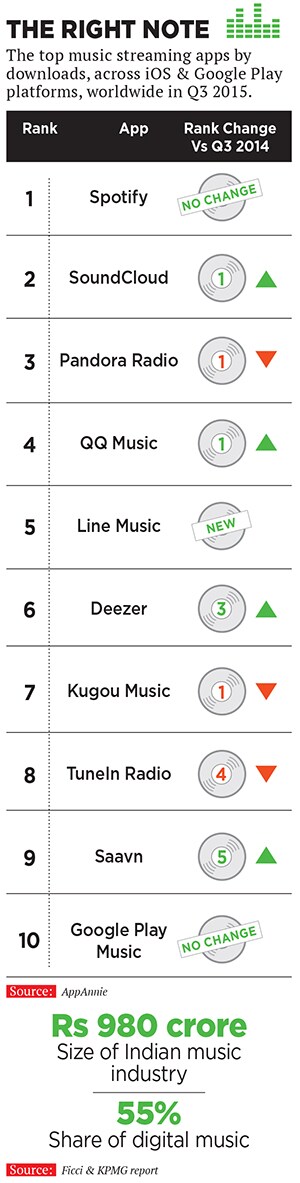

Today, the service that they went on to create is one of the largest music streaming companies (by the number of downloads) in the world. In early December, a report by mobile intelligence platform AppAnnie titled ‘Mobile Music Streaming: Driving the Next Digital Revolution’, ranked Saavn the ninth most popular music streaming application worldwide on Google’s Android platform for the third quarter of 2015. Saavn’s closest Indian competitor Gaana—backed by Bennett, Coleman and Company Limited—was at the 10th spot. Saavn was also ranked ninth most popular when the report considered the combined downloads for Apple’s iOS and Google Play app stores. It was the only service with Indian content on the combined list. In July last year, the company raised $100 million (around Rs 670 crore at current rates) in a Series C funding round led by Tiger Global Management that also included existing investors Bertelsmann India Investments, Steadview Capital, Liberty Media and Mousse Partners.

Much has changed in the five years of Saavn’s existence as a consumer-facing music company. Digital music in India, which was until a few years ago limited to caller tunes and ringtones, has now become the predominant source of legally consumed music. The ‘Indian Media and Entertainment Industry report 2015’, compiled by industry body Ficci and consulting firm KPMG, pegs the size of the Indian music industry at Rs 980 crore. It estimates that digital music accounts for 55 percent of the overall music market. This includes caller tunes, online stores like Google Play and iTunes and music streaming services. Since it was the first music streaming service focussed on Indian content, Saavn’s journey has also been representative of the burgeoning Indian music-streaming industry.

“In principle, the challenge of piracy affected all markets. The solution to that, in the music industry, was to use technology to stream music legally through subscriptions,” says Smita Jha, leader, Entertainment & Media Practice India, Pricewaterhouse Coopers. When the record labels in India failed to digitise and distribute their content at scale, to offer a seamless experience to consumers, music streaming services stepped in to fill the void.It was in this void, following their split with Hungama Digital, that Saavn.com was launched as a music streaming website in June 2010. The relationships that had been forged by its founders in Saavn’s B2B avatar now became a valuable asset. “We were talking to labels since 2006 and had been evangelising digital music since the beginning,” says Singh. As a result, when the website was launched, Saavn already had several major Indian labels on board.

In 2010, Google was also in the process of ramping up its India operations. “They got in touch with us and told us that of all the searches made on Google in India, around 20 percent was related to the data that we had collected,” says Singh. “We were pretty blown away.”

This led to the first of many partnerships that would fuel Saavn’s growth. With Google, they launched One Box, which consisted of a media player along with a search display. This essentially meant that whenever someone searched for Indian music on Google, a Saavn widget would pop up. Unsurprisingly, “this brought us a tonne of traffic”, says Singh.

Following the success of the partnership, Google asked Saavn to build an application for the Android platform, which was then in its infancy. Although Saavn had been toying with the idea of creating an app, they didn’t know how to build one. “We literally drew out the wireframe, step by step created the app on paper and then had our engineers code it,” says Singh, of the app that was launched in 2011.

Even up until the app’s launch, the company was, for the most part, funded by the founders’ friends and families. Following the app’s launch, in 2011 they received their first round of funding from Tiger Global Management. And in 2012 they launched a Saavn app on iOS.

“Through our investors at Tiger Global, we were introduced to the right people at Facebook and we struck a partnership with the social network,” says Singh. Although Facebook had struck similar deals with American music streaming services in the previous year, in 2012, Saavn became Facebook’s first international Open Graph partner. This meant that if any Indian song that was in Saavn’s catalogue showed up on a Facebook user’s feed, on clicking it, the track would redirect and play on Saavn.

Although both these partnerships ended after some time, Singh believes they were immensely valuable. “At that time, it was great for us. They helped us build the brand and sign up users,” he recalls. There were others that have sustained. It has, for instance, partnered with Shazam, the global music discovery service. In 2014, it even created ‘Tweet-powered’ radio in collaboration with the micro-blogging site Twitter. This enabled Saavn’s followers to tweet song requests for its radio feature.

A period of growth and consolidation followed. “Android became the big story in 2013 and we watched our user base grow exponentially,” says Singh. The trend has continued well into 2015. Saavn recently announced that it had 18 million monthly active users (MAUs), a number which, it said, is three times what it was 18 months ago. It also claims that its library contains 20 million licensed tracks.

But while its own numbers have grown, so has the competition. Gaana remains the largest among Saavn’s rivals. Although it arrived in 2011, Gaana quickly caught up and now claims to have 20 million MAUs.

“Practically, there are only a few basic things that companies can do in order to differentiate themselves in the market. One is developing the library of content, which includes exclusive content. Then there’s the consumer experience in terms of delivery of the content, and finally, the financial aspects of the business,” says Jha.

While the first two factors are largely congruent with global trends, it is the financial aspect that is somewhat different in India. “Right now, about 75 percent of our revenue is from advertisements and the rest is from subscription,” says Malhotra, who is now the company’s CEO, having switched positions with Bhat in 2014.

The fundamental challenge that the Indian music streaming industry faces is to make streaming more attractive than piracy. The Ficci-KPMG report estimates that only one to two percent of the music consumed in India is legal. Interestingly, Bhat believes that in many cases, piracy is already a subscription model. “There is subscription happening in the offline world, where people go to their local shop and buy a memory card with music stored in it and return a month later to buy some more,” he says.

The freemium model, a combination of free and premium offerings, has emerged as the most compelling way to lure Indian users, who are now accustomed to free music. Most music streaming services in India offer free music streaming on their platform with the option of a paid premium subscription that enables high-quality streaming and downloads. The only differentiators in this regard are the price points, which vary marginally, but can be crucial in a value-conscious market like India.

While free streaming continues to dominate, many believe that premium subscriptions will eventually offer the path to sustainability. Globally, even freemium’s biggest proponent, Spotify, has shown signs that it is conscious of the pitfalls of this model. Although the company had previously been unwavering in its support for free streaming, it has shown signs of caving in to the demands of the music industry.

Earlier this year, it was reported that Spotify was contemplating a premium-only release of Coldplay’s latest album. Spotify eventually released it to all its subscribers, but the message was clear: Free music can only go so far.

However, “the subscription model can only work if you are able to showcase a concrete value proposition to your consumer,” says Debashish Ghosh, CEO, Zee Digital Convergence Ltd, which runs the subscriptions-only video streaming service, Ditto TV. Exclusive content is still limited, and for now, advertising remains the mainstay for most music streaming services in India.

Saavn first experimented with banner advertising in their early years, but the click through rate (CTR) was abysmal. “In 2014, right around when Rishi and I transitioned, we came up with the native ad platform,” says Bhat. They divided a user’s listening time into 15 minute packets and integrated a display ad with an audio interruption. Bhat claims that with these changes Saavn has improved its CTR from an abysmally low 0.007 per cent to about 4.5 percent.

The concern about sustainability of models based primarily on ad revenues though, still remains. However, Malhotra believes that as companies scale, growth in ad revenues will follow. Besides, music streaming companies in India aren’t just disrupting an existing industry. For instance, says Bhat, “the radio market in the US is about $22 billion and Pandora is going directly after that. But in India, we’re creating the market.”

A report compiled by industry body Internet and Mobile Association of India (IAMAI)—of which Vinodh Bhat is vice chairman—and KPMG titled ‘India On The Go: Mobile Internet Vision Report 2015’, estimated that the number of mobile internet users, which stood at 159 million at the end of 2014, would grow to 314 million by 2017. With rapid internet penetration, and a market that is still at a nascent stage, Ghosh believes that questions about sustainability are premature. “I’m surprised that people are seeking answers so early in the game. Television penetration didn’t mature for 15 to 20 years, and newspapers took over 100 years to mature,” he argues.

In a space that seems to have all the right ingredients for spouting winners, it may all come down to the number of players that the market can sustain. “We think it’s going to be a winner-takes-all market,” says Bhat. “If you take a step back and look at streaming generally, there are battles raging across the entire landscape and winners are emerging.” Spotify, SoundCloud and Pandora have emerged as the dominant forces in music streaming globally, with the AppAnnie report showing that Spotify is the most popular among them.

As for Saavn, Singh believes that the $100-million dollar injection of funds is exactly what it needs to pull away from the competition. “This is our escape capital,” he says. Following the fundraising, Saavn has announced that it will look to create original content to increase the size of its exclusive content base. Video streaming may also be on the cards soon. “I think it will come later. There’s a certain user milestone that’s important for us to hit,” says Malhotra.

For now, as Gaana and Saavn vie for the top spot, telecom companies like Airtel (Airtel Wynk) and Vodafone (Vodafone Music) have also launched their own streaming services.

YouTube, which has long cast a shadow with its potential to disrupt music streaming, finally launched YouTube Music in November 2015. Apple Music is already a large entity in India. Add to that the entry of foreign players like Australia’s Guvera, which reportedly raised $100 million recently to aid its expansion in India, and you have a sector that is primed for a showdown.

First Published: Jan 27, 2016, 07:45

Subscribe Now