The Men Who Made Microfinance Work

Two different personalities. Two different methods. Two successful companies. Why Chandra Shekhar Ghosh of Bandhan, and Samit Ghosh of Ujjivan are beacons of hope for microfinance companies

Chandra Shekhar Ghosh

Profile: Founder of Bandhan

Education: Son of a sweet vendor, went to Dhaka University, studied statistics, got into an NGO purely to make a living

Quote: Give me a day, and I will give you the future

It would seem there is nothing common between Chandra Shekhar Ghosh, founder of Bandhan, and Samit Ghosh, founder of Ujjivan—two microfinance institutions (MFI)—other than their second names.

Chandra is slightly built, walks with urgency and is almost always seen in pants and shirts. Son of a sweet vendor, he went to Dhaka University, studied statistics, got into an NGO purely to make a living. His English is a bit halting. His office looks tidy and professional, as if it was designed by an architect who likes to go by the book. All these qualities evoke a deep sense of loyalty, and even reverence among his colleagues.

Samit likes food—and his fish—and it shows. He looks like a person who feels most comfortable in a kurta. Son of doctor, he went to Wharton for his MBA, worked in Citibank and Standard Chartered, and had a long stint outside India. When he speaks to his friends, he is self-deprecating, and uses the word ‘yaar’ often. The office he sits in used to be a garment factory, with high ceilings and wide doors. His wife redecorated it. (“And so, we didn’t spend anything on an interior designer,” he says). When he walks around, junior colleagues think nothing of stopping him to exchange a word about this or that.

The businesses these two people run are different too. Their target customers are different. Bandhan focusses primarily on rural West Bengal. Ujjivan’s target is the economically active urban poor. Bandhan is based on Asa model—which is comparatively low cost—and Ujjivan follows Grameen model. Bandhan is older and bigger, and Ujjivan is relatively new and small.

Yet, Chandra and Samit often find themselves on the same page in the newspapers these days. They are the new poster boys for the microfinance industry.

The reason is simple. While most MFIs have been shrinking their business during the last two years, the outstanding loans of both Bandhan and Ujjivan have grown. Bandhan, in fact, overtook SKS as the largest MFI late last year. Their recovery rates are still above 95 percent. While bankers and equity investors are shying away from the sector ever since Andhra Pradesh ordered MFIs to suspend operations in the state, both these firms have found it easier to raise funds, importantly equity. Last month, Bandhan raised Rs 500 crore from IDBI in a securitisation deal, and a few months before that Rs 135 crore as equity from IFC. Similarly, Ujjivan raised Rs 127 crore from its existing investors.

What makes them click? The reasons reflect the differences inherent in the personalities and organisation. Former chairman of Nabard Yogesh Chand Nanda says he was impressed with the way Bandhan has managed to integrate its social development activities with microfinance. He is now on its board. Sucharita Mukherjee, CEO of IFMR Capital, which helps MFIs raise funds and has worked with Ujjivan, says that its underlying systems and processes sets it apart, and helps them provide consistent quality of operations across the segments they operate in. Another factor is the quality of second-level leadership, she says.

Are there common strands? To find out we need to go back, and dig a little deeper.

The Tale of Two Ghoshs

Old timers remember Kolkata of the ’60s and ’70s for the music of Pam Crain and Carlton Kitto and night clubs with evocative names such as Mocambo and Moulin Rouge. But the ’60s and ’70s was also the time when the Naxal movement was gaining grounds in the campuses of Jadhavpur University and Presidency College. Among the idealistic students it drew into its fold was Samit Ghosh. In the end however, he was disillusioned by the way the movement turned out to be. A few years later he found himself in Wharton.

When he started Ujjivan—his motive was to find professional fulfilment, to round off his career in banking with serving the poor—it was with a sense of hard-nosed idealism that, at the end of the day, recognised micro credit as a loan product. Most MFIs were focussed on the rural areas, and ignored the huge market for micro credit in the cities and small towns. Of the 600 million poor, 100 million were in the urban areas, mostly untapped. He decided to focus on that segment. Carol Furtado, COO—South, Ujjivan, says he kept away from Andhra Pradesh for the same reason: The state was too crowded by other MFIs.

Samit Ghosh

Profile: Founder of Ujjivan

Background: Son of a doctor, did MBA from Wharton, worked in Citibank and Standard Chartered, had a long stint outside India

Quote: If you don’t keep your employees happy, you can’t keep your customers happy

On a recent afternoon in its branches in Jakkasandra, Bangalore, Ujjivan’s second floor office was filled with customers who had come to collect their loans. N Nanjamma, who works in a garment factory and first heard about Ujjivan through a neighbour, said she had an account with a regional rural bank in her village, Gowribidanur, but none in Bangalore. She teamed with four others to avail a loan a few years ago, and is in her fourth cycle now.

Samit also noticed that few MFIs were focussing on the back end. He felt that making the back end efficient will help in building an organisation that will be ready for the future. And the future will be very different. The joint liability model will fade away—which means the credit evaluations will have to be stricter. High recovery rates will drop—which will increase the cost even more. There will be more products—and the systems will have to be robust.

In short, an MFI of future will look like a bank of today, and that’s when the initiatives he is working on will help. It includes building a strong back end, making the processes rigorous, building credit evaluation skills for individual loans and start initiatives to keep the employees happy.

Chandra’s story is nothing like Samit’s. He went to Dhaka University across the border. After a degree in statistics, he joined Brac, one of the three big NGOs in Bangladesh, because it was the first to offer him a job. “We were poor in those days,” he says. His family members were refugees and his father had to struggle to send him to college.

His first lessons in how to deal with poverty came in Brac, from the stories he heard and what he saw on the ground. One was about Fazle Hasan Abed, Brac’s founder. When Abed was teaching some elders in a village, a young girl suggested that this would be a never ending task. For by the time he finishes teaching them, a new batch—her generation—would be ready for adult education. That pushed Abed to open schools. Lesson One: Think long term. Don’t just focus on today’s problems.

Chandra himself got a taste of the rustic commonsense when, during one of his trips, he gave a lecture on hygiene to a woman. She said she knew all about hygiene, but what she didn’t have was food to feed her child. Lesson Two: There can be no silver bullet. Your approach needs to be holistic.

In 2001, he set up Bandhan to primarily give training to other MFIs, but in mid-2002, he decided to enter the business. The first branch was set up at Bhagnan, 60 km from Kolkata. He took Asa’s help in setting up the MFI, but tweaked the model with the lessons he had learnt.

When Asa proposed a training schedule for employees on ‘how to identify the poor’, Ghosh struck it down, and said he will recruit the poor who will know what poverty is.

The branches are frugal and even paternalistic. All the staff members make a promise that they will never misbehave with clients, will never play cards or gamble, will not have affairs with women. Chandra hammers these lessons tirelessly. (Asked about this, Chandra says, “When people say it’s not freedom, I ask them, ‘will your father allow you to do all this? Then I wouldn’t too.’ ”)

“You have to look at the ownership structure to understand why Bandhan is different”, says Rajendrakumar Thanvi, DGM at Nabard, Kolkata. It’s marked by the absence of private equity players. Chandra says when he raised about Rs 50 crore in 2009 from SIDBI - Small Industries Development Bank of India, some investors offered higher valuation. But, it choose SIDBI, because that bank understood Bandhan’s mission and method better.

SIDBI gave Bandhan the freedom to integrate non-profit, development activities with microfinance. When it started a retail training programme, it gained an entry into retail chains by first asking for free internships. Now the interns get stipends and get placements in the chains. The aim is to become a training-cum- placement agency. (But it will remain non-profit, Chandra says).

One of its new initiatives follows a similar pattern of connecting its customer base with new opportunities. He is in the process of setting up a business that’s a bit like Fabindia—to the extent of connecting artisans with the market. To be called Bandhan Creations, it will bring in additional income.

Road Ahead

In some ways, the progression of Bandhan and Ujjivan follow a pattern set by many other microfinance companies in India. MS Sriram, a former professor of IIM Ahmedabad who has studied the sector, says the entrepreneurs created organisations in their own images—based on their background, interests, strengths and personalities.

Thus, Tara Thiagarajan, who came with faith in science and scientific approach, is building an organisation that reflects her vision. Nachiket Mor, who came in with an implicit trust in branch banking, helped in the creation of KGFS, a low cost regional rural bank. PN Vasudevan who spent several years at Cholamandalam is moving equitas in the direction of an NBFC. SKS, of course, continues to reflect the complex personality of Vikram Akula.

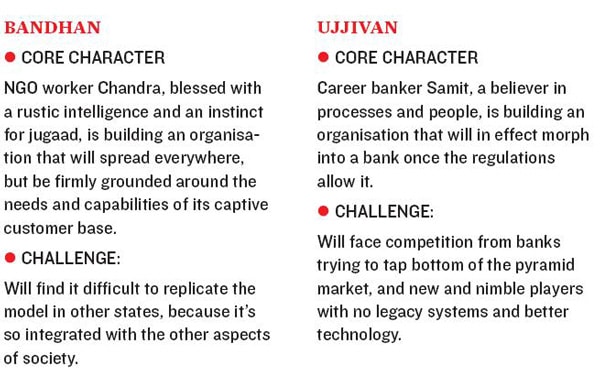

So does Bandhan and Ujjivan. Career banker Samit, a believer in processes and people, is building an organisation that will in effect morph into a bank once the regulations allow it.

And the NGO worker Chandra, blessed with a rustic intelligence and an instinct for jugaad, is building an organisation that will spread everywhere, but be firmly grounded around the needs and capabilities of its captive customer base. The path won’t be easy for either. Samit will face competition from banks trying to tap bottom of the pyramid market, and new and nimble players with no legacy systems and better technology. Chandra will find it difficult to replicate the model in other states, because it’s so integrated with the other aspects of society.

What connects them both—and why they are different from some of the earlier crop of MFI promoters—is an awareness of the limits of microfinance and willingness to build a model that will transcend microfinance. “For an MFI, the only skill that’s required is cash collection. You don’t need to understand customers well, because you only have a single product. You don’t need to worry about the credit evaluation because the joint liability structure took care of that. That leaves only the cash collection,” says Bindu Ananth, president of IFMR Trust. Many MFIs, safe in the knowledge that microfinance held an exalted position, focussed only on scale.

Bandhan and Ujjivan did not give that status to microfinance in the first place. And that is where their promise lies.

First Published: Apr 03, 2012, 06:19

Subscribe Now