Sankaran Naren of ICICI Prudential MF does things pre-mortem than post-mortem

Rigorous research has been the backbone of ICICI Prudential’s decisions to go against the mutual fund tide, and emerge successful

Sankaran Naren has an enduring nightmare: The crowd is right, he is wrong, and nobody wants the stocks he has stockpiled.

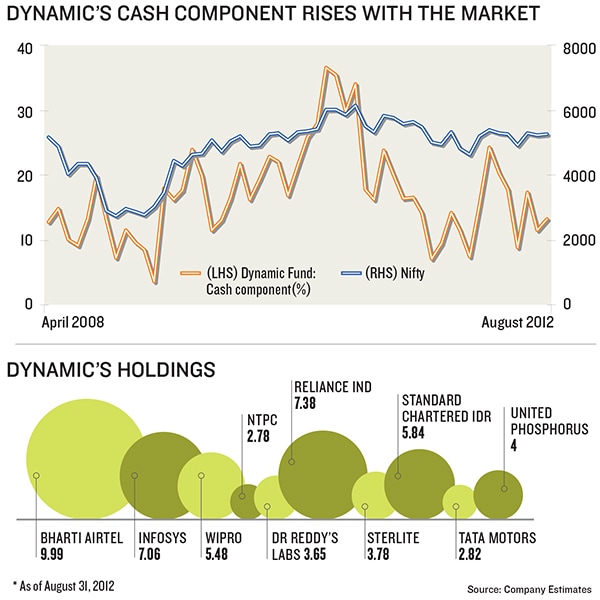

It is a genuine fear for someone who likes to go against the grain. The nightmares will continue for the time being because Naren’s current favourite is Bharti Airtel. This stock has been a poor performer for the past one year. It has lost 40 percent of its value in the past year during which the Sensex moved up 15 percent. And Naren has invested close to 10 percent of the portfolio for one of his funds, Dynamic, in Bharti.

For most part of his life, Naren, chief investment officer, equities, ICICI Prudential Mutual Fund, has picked up and bet big on stocks that have been out of favour. If it wasn’t for his record, his bet on Bharti would look like a loser’s gamble. But his numbers speak otherwise.

Naren started managing the Rs 1,800-crore Discovery fund immediately after joining ICICI Prudential in October 2004. Mrinal Singh took over from him in February 2011. According to Morningstar India, a mutual fund analytics company, over the past three years, the fund has given an annual return of 13.88 percent, one of the highest in a flat market. The other fund in Naren’s stable is the Rs 4,000-crore Dynamic fund, which has shown a similar performance: Over the past three years, it has given an annual return of 10.19 percent, against a category average of 5 percent.

Cash as A weapon

Contrasts make humans interesting, and the Bharti call exemplifies that.

Naren is not afraid to remain in cash the idea is to realise profits and look for another buying opportunity when the stock cools off a bit.

The Dynamic fund is one of the very few that can park itself into cash to the extent of 35 percent of its assets. Fund managers do not like to get into cash because it can mean either a missed opportunity, or the fund manager doesn’t have any interesting ideas. Most funds take cash positions to a maximum limit of around 10 percent of assets, or it depends on the mandate of the fund.

ICICI Mutual Fund has benchmarked the cash positions to the price/book value of the Nifty. If this crosses 3.5 times, Dynamic can utilise its cash position to the extent of 35 percent of assets. The fund used this structure in September and December 2010. This was done when the markets were trading at very high levels, and Naren thought the valuations were not sustainable. The idea of getting into a massive amount of cash has given Dynamic a big advantage.

Naren is also one of the few fund managers to use derivatives to make his portfolio more defensive. Using derivatives hurt him in 2009, when the market went up 70 percent in a few months. But that is the nature of the business. People who know him well understand that once he thinks it through he will not shy away from a bold call.

“Apart from taking sector bets, Naren doesn’t shy away from aggressively trading his large-cap investments,” says Vickey Mehta, senior research analyst at Morningstar India. Naren was buying in the pharma sector long before the great domestic tailwind for pharmaceuticals became apparent after 2008. He built a large position in metals in 2011, and that helped him beat the index in early 2012.

Early start

Naren spent most of his time playing bridge at the IIT Madras campus, and was clear that he wanted to play the equity markets as well. While in college, whatever money he earned he invested in IPOs. And, on getting a job after completing college, he invested his first salary in L&T.

He was a bit of an information hound at that time, and continues to be one: Around 15 newspapers await his attention every day he devours anything that tastes like business information, especially balance sheets he is known to go through the wrappings of his evening bhelpuri or sandwich in search of information close colleagues say he carries balance sheets on his annual vacation.

Sometime in 1996, he started working with a Chennai broker and joined a group that was interested in equity markets, but there was no form to their investment style. Naren helped the group evolve to a bottom-up style of investing. He has kept in touch with this group over the past 16 years, and some of them are his closest friends.

The equity markets had just opened up to foreign mutual funds and Kothari Pioneer, the first private sector Indian mutual fundwas looking to build an equities team in Chennai. (Kothari Pioneer was taken over by Franklin Templeton in 2002.) Naren approached them for the position of a fund manager, but Kothari Pioneer was looking for someone from Mumbai.

Meanwhile, Siva Subramanian KN, who was working at IDBI, Mumbai, was looking to head back to his hometown Chennai. With a solid background and his experience in Mumbai, he fit Kothari Pioneer’s requirements and joined the firm. Later, he became its chief investing officer.

Naren and Siva have known each other from their IIM Calcutta days, where Siva was a year senior. Both shared a passion for equities and value investing. While Siva developed a bottom-up strategy for investment, Naren now uses a top-down approach, based on macro analysis. Today, both their flagship funds have a huge holding in Bharti Airtel (Siva’s holding is 5.8 percent), where Naren runs a slightly more concentrated position.

Wisdom of the 3Ms

Naren has built his strategy on his understanding of what he calls the 3Ms—Howard Marks, James Montier, and Michael Mauboussin. Marks is a billionaire and the chairman of Oaktree Capital. Mauboussin and Montier are investment strategists very well regarded for their ideas on behavioural finance. One of the key things that Naren learnt from Mauboussin, for instance, is that fund managers should not be ideological bulls or bears.

Mauboussin feels they should take advantage of the market situation, whatever that may be. “I have learnt that one should do everything premortem [sic]. No need to wait for postmortem,” says Naren.

Now, to become proactive, you need to put in the hard yards well before the opportunity presents itself. Without this rigour, chances of the bet going wrong are far too high. After the Lehman crash in 2008, Naren and his then boss Nilesh Shah set out a new approach to rigorous research process.

Naren wanted to make his team sceptical about the way markets worked. He is a big fan of Atul Gawande’s pathbreaking book The Checklist Manifesto. The book talks about how following a one-page checklist is more effective than reading 20 pages of ineffective documentation. It is a book Naren wished was written in the 1990s, so it could have helped him develop a simple and rigourous process ahead of time.

“Earlier, research was being done in a way that everyone was following their own style. We institutionalised it into a system called PruSearch, which was aligned to the broad organisation. This way, we were able to capture every thought into our portfolio building process,” says Mrinal Singh, who manages the Discovery fund.

Rigour before gut feel

The processes helped Singh spot one of his biggest bets, Natco, a pharma company that he holds in his Discovery fund. Natco was famous for its cancer drugs and was operating in a niche market. Singh had come to know too many things about it, and that its competitors were its biggest admirers.

The process helped Singh be sceptical about the company and only after doing thorough research did he approach Naren for his opinion on the company. Naren had also learnt independently that Natco products were very popular with pharma distributors. The fund hired an external pharma research firm in New York for a technical view about the company.

Natco was small, and was initially held in the midcap fund at an average price of Rs 245 before Discovery purchased it. Today, Natco’s stock price works out to around Rs 370.

Singh feels processes have become really important in the case of small companies, where research takes top priority.

“Naren was very sceptical in 2008, and decided to get into stocks that the street didn’t believe in. He was convincing when he put his proposals on the table. Eventually, after a lot of argument, we decided to go with him,” says Mittul Kalawadia, head of research and co-fund manager, Dynamic.

It was a time when capital goods were being traded at a price/earnings multiple of 40 times. Naren, who always believes in buying cheap, decided not to touch the overvalued sector, and started to buy pharma, which had an average price/earnings multiple of 12.

This was the time when nobody

was interested in pharma. Naren was doing his research, and accumulating pharma stocks for Discovery in 2006-07. He started buying Cadila Healthcare. The company had lost a court case related to the drug Pantoprazole and its stock price had crashed. Naren and his team were bullish on the company, but their call was a long-term one. The average price of acquisition for the stock worked out to around Rs 300. Today, the stock is around Rs 835.

Since he did not buy into sectors like real estate, construction and infrastructure, returns started to suffer. “Once a sector goes above the price/earnings multiple of 25, I become very uncomfortable. Because of this I have missed many opportunities, but that is fine. I still believe in buying stocks that are ignored by the market, rather than those that still have a lot of steam in them,” Naren says.

First Published: Oct 16, 2012, 06:30

Subscribe Now