Mahesh Tutorials: Looking Beyond Classrooms

Mahesh Shetty's strategy for scaling up the usually 'localised' tutorials business is based on standardising teaching processes. And, to overcome the constraints of the brick and mortar model, he now

Mahesh Shetty was a worried man. The year was 2005, and it was soon after the sudden death of his accountant, Atul Dhaga, due to a heart attack. The tragedy of the loss of a 36-year-old who had worked with him for a decade was only compounded by this quandary: Dhaga’s demise had left the finance department at a standstill. What if something was to happen to him? Shetty feared his business would become rudderless as would the people who had been working with him for the last 17 years.

He decided it was time for Mahesh Tutorials, his coaching class business, to become a corporate entity that would survive independent of his presence. “As a corporate, the company would be taken care of whether I am a part of it or not,” says the 49-year-old.

His classes, a Rs 25-crore partnership firm at the time, had acquired cult status in the unregulated Rs 2,000-crore tutorial industry for Class 10 board exams (the industry size is as per company sources). This transition, as Shetty envisioned it, was based on building redundancies—not allowing anyone to become indispensable. This philosophy has carried forward to the super-standardised method of teaching that defines the success and growth of his tutorial business.

That strategy seems to have worked. Consider the growth trajectory.

In 2006, Mahesh Tutorials acquired businesses that led to it getting rebranded as MT Educare. And, in 2007, it finally became a corporate entity with Helix Investments as a private equity (PE) partner. Its turnover in 2008 was around Rs 44 crore the PE firm invested around Rs 32 crore for a 30 percent stake. Five years on, for FY2013, the company has a turnover of Rs 154 crore with a net profit of Rs 18 crore and a market capitalisation of Rs 400 crore.

In April 2012, the company was listed at Rs 90 against an issue price of Rs 80, allowing Helix to sell 25 percent of its stake for a 2.5x return. Currently the stock trades at Rs 102 per share.

Marquee investors such as Shivanand Mankekar, with a net worth of Rs 355 crore and known for his early investments in Pantaloon and Radico Khaitan, picked up around five percent stake (along with his wife) at the IPO stage. The institutional shareholding has gone up to 27 percent as on September 30, 2013, against 23 percent last year, even though the share is underperforming the markets by around seven percent. Shetty is also buying back his stock from the market and has increased his stake from 43 percent to 45 percent since March 2013.

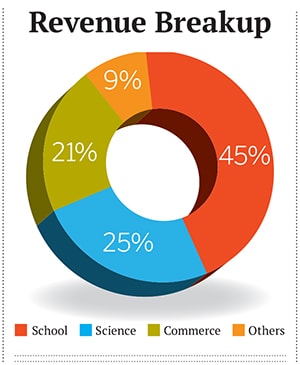

And the business has expanded beyond just teaching mathematics to Class 10 students it has entered the commerce and science streams as well (these now account for 50 percent of the turnover).

Despite the apparent growth, some analysts believe that MT Educare has peaked as the business is very local and expanding into newer cities is not easy.

“Margins get sacrificed with growth, thus many competitors don’t want to scale upwards,” says a competitor who had worked with the company earlier. But the management is confident that MT Educare can become a Rs 500-crore business in the next five years. And institutional investors are biting.

Avendus Capital’s Fund III, an Alternative Investment Fund (AIF), has recently purchased a 2 percent stake in the company. “MT has an asset light business model with negative working capital and low capex. The business generates very good cash flows and has a high return on equity. We also believe that India is starved for good education institutes and supplementary education will continue to be in great demand,” says Manoj Thakur, CEO, Avendus Capital-AIF.The opportunity is evident. According to the Department of Industrial Policy and Promotion, the market for India’s education sector is around Rs 3.41 lakh crore and has been growing at roughly 15 percent over the last five years. Crisil, a rating and research agency, says the coaching business is expected to expand at 17 percent CAGR, from Rs 40,187 crore in 2010-11 to Rs 75,629 crore in 2014-15, on the back of rising disposable income and infrastructural bottlenecks in the formal education sector. MT Educare is targeting board exams, engineering and medical entrance tests and CA exams.

The young teacher who couldn’t afford to pay the rent for his new business premises has indeed travelled a distance.

Shetty’s first teaching assignment was with Shetty’s Academy (no relation) in Mulund in 1984. He had completed his Bachelor’s from Ramnarian Ruia College in maths and statistics. The job did not pay well—he earned around Rs 500 a month.

Shetty, whose father worked with IDBI Bank, knew that if he took up a job with a bank, he would probably earn around four to five times more. But it was not about the money. He liked the idea of teaching, with all the associated problems.

The classes went on for eight hours also, the continuous writing on the blackboard created throat problems that are typically associated with chalk dust. But he was so well-prepared that, often, he was not in a position to talk to the students but they still chose to attend.

By 1988, Shetty had acquired a cult following in the small Mumbai suburb of Mulund which was known for its well-to-do middle class. It was around that time that he had a falling out with Shetty’s Academy.These two factors—his popularity combined with the discord—led to the launch of Mahesh Tutorials on November 24, 1988, near St Pius Church which was located close to two of the most important schools in that area.

His plan: To build a coaching academy that creates world-class teachers who are also well paid. Inevitably, as he moved into the small shop floor space to start his new classes, almost all his students followed suit. “That was not my intention. I never wanted to move with all the students. They just followed me,” Shetty says.

The classes started but he did not have the money to pay rent for the premises. And the 130 kids who had moved with him had already paid their fees at Shetty’s Academy. Since it was November, they had only about four months to go before their board exams.

Shetty decided to not charge these students as they would have to pay twice. But on learning that he was in financial trouble, Pushpa Bhagwan, the mother of a Class 9 student, got in touch with the other parents and asked if they would be willing to pay the annual fee in advance. They agreed and the first roadblock was surmounted.

“It was the simplicity that he brought to the class ... once Mahesh explained the concept, it kind of stayed with you permanently,” says Murli Subramanium, an ex-student at Shetty’s Academy who now works at MT Educare.

The students kept coming, despite the fee disparity. MT Educare charged Rs 1,000, a one-time annual fee for science and maths for Class 10, while its closest competitor in the same area asked for around Rs 200, that too in instalments.

Ironically, his own popularity had started worrying Shetty. His students had joined the class because of his teaching style. If the business had to grow in size, it became important to create more teachers like him.

The first step was conducting workshops with teachers to understand the difficulties being faced by students. That led to standardised solutions and teachers who were replicable.

But this process needed educators who did not carry any baggage. Shetty wanted young individuals who were open to his vision of teaching. By 1990, he had created three maths teachers who followed the same principles as him: Shetty did not show his back to the students he kept the blackboard writing to a minimum, maintaining eye contact with the students most of the time.

These eventually became part of the standardisation. The idea was to move the focus away from the teacher and to the student.

Interestingly, most of the senior managers of MT Educare are former students of Shetty. They understand the idea of creating Mahesh Shettys out of the teachers and believe in a process-led approach towards teaching.

But while these steps were taken, Shetty, an educationist, did not know how to completely ‘corporatise’ his classes. Enter Chhaya Shastri who, at the time, was an advisor to Polymath, an investment banking firm. She specialised in turning small and medium enterprises into big-ticket corporates.

In 2006, Shastri was helping Neptune, a real estate company which wanted to raise money from the markets. Neptune was started by Shetty’s friends who wanted him on the firm’s board—and that was how he met Shastri.

He asked if she could help in the transition process at Mahesh Tutorials too. She found the business interesting and started to visit the office every Saturday.

The firm was already at Rs 25 crore with 20 branches. For it to become a Rs 100-crore venture, she needed to prepare it for PE investment. Shastri knew that investors would ask questions related to scalability and sustainability.

But the good news was that the business was asset light and operated on a negative working capital. It generated free cash flows and there was a visibility of revenue for at least three years. More importantly, it had a consistent return on investment of around 20 percent.

Despite that, when she went on a road show to the Middle East, investors were doubtful about putting money into supplementary education. The business was looked down upon by many and it was believed that the company would cap its growth at Rs 40 crore.

There was also the issue of the ‘star teacher’ model and low margins to boot. Nobody quite bought into the process-driven approach of the company that, to Shetty’s mind, assured scalability.

The impetus came when Shetty decided to get into chartered accountancy (CA) coaching classes in 2006. At that time, SK Thakkar, who too operated from Mulund, was the biggest name in CA coaching in Mumbai. Shetty had a meeting with Thakkar and discussed his vision. Thakkar was convinced enough to sell him his classes.“In the very first meeting, I realised that Mahesh Shetty had a very clear vision about how to take forward the coaching class business,” says Anish Thakkar, who now handles MT Educare’s CA vertical, the biggest across India. He has a 30 percent pass ratio for the CA final classes against an all-India number of 10 percent (source: ICAI). This acquisition meant they were getting clearer in their growth strategy. Shetty also bought Lakshya for IIT prep and CPLC for MBA coaching.

Later that year, Mahesh Tutorials brought all the partnership classes under one umbrella: MT Educare. During the same period, Polymath introduced Shastri to Helix Investments, a private equity firm that belonged to the Bloomingdale family, known for its Bloomingdale's chain of stores.

The fund was looking for long term investments in the Indian market. David Danziger, a director with Helix Investments, visited the MT Educare office and was sold on its idea of growth.

On August 17, 2007, Helix offered Rs 48 crore but MT Educare needed only Rs 32 crore. The turnover at the time was Rs 42 crore.

“I think Danziger really understood what we were planning to do. He asked us the right questions. We were happy that someone believed in our story,” says Shastri.

She now owns five percent of MT Educare and actively looks after the strategy. Helix entered the company at an average cost of Rs 32 and exited at Rs 80 when it was listed in August 2012 it still owns five percent of the company.

“We liked the fact that teachers were empowered and had a career path and the entire teaching methodology was process driven. That enabled scalability,” says Sumit Tayal, director, Helix Investments Advisors India.

MT Educare gets fees upfront from the students and is in a position to operate on the negative working capital model. The fees that are received are treated as deferred revenue into the current liabilities and are booked as revenues only after the services are delivered.

Since the business generates cash, it also has the ability to create a higher return on equity (RoE). But MT Educare’s RoE is down from 23 percent in FY2012 to 18 percent in FY2013.

This can be attributed to the IPO proceeds that added to the net worth—the funds were used to build a college in Mangalore as a proof of concept to get into the Karnataka market.

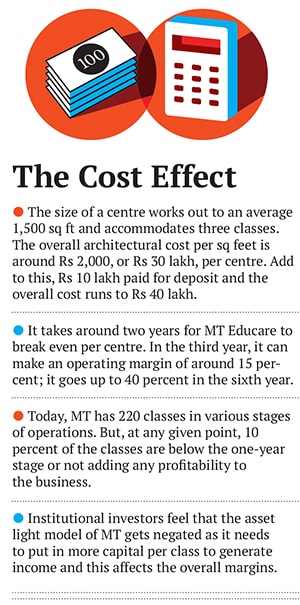

Now, while the issue of scalability continues to nag MT Educare, investors are also concerned about the amount of capital that the brick and mortar business consumes (see The Cost Effect). This is why, over the last year, the company has started to dabble with technology by reaching out to students in classes 5 to 8 via the internet.

Currently, they have around 500 students in this module where one teacher holds an online class for 10 students each. Shastri says that eventually these students will stick around for classes 9 and 10 too. This product, called Ink, or integrated network knowledge, is expected to be the main driver for MT Educare in the future.

The company has started to record these lectures and is now selling them separately as another product called Robomate.

In terms of the offline model, however, Karnataka has become the biggest bet for MT Educare. The company has tied up with nine pre-university colleges in the state.

It generates income from two sources here: One, for administratively managing the colleges and the staff, with MT getting 15 percent of the college fees. Two, from test preparation or coaching classes conducted on the college premises.

The company keeps 85 percent of the coaching fees 15 percent goes to the college trusts. The pre-university colleges are co-branded and, today, account for eight percent of MT Educare’s revenue.

If that doesn’t answer the question of scalability, Shetty crunches the numbers for us: 220 coaching centres across India addressing 80,000 students with a faculty of 2,015.

And, as for creating an organisation that isn’t dependent on one individual, the worrylines on Shetty’s forehead seem to have been smoothened. The cloning has been successful. Evidence: Shetty stopped teaching a few years ago.

First Published: Nov 27, 2013, 06:41

Subscribe Now