Jet's 180-degree Turn

With the backing of the deep-pocketed Etihad, Naresh Goyal is returning the airline to its full service model to reclaim its place in Indian skies

Six years ago, the senior management at Jet Airways undertook a rather curious exercise. The airline was launching a new brand but, unlike previous Jet events, the rollout—led by then Chief Commercial Officer Sudheer Raghavan—was quiet. In May 2008, the airline began pulling its Boeing 737 planes out of service, one by one, and painted them light-blue and white. It removed the 24 plush seats in its business class, replacing them with 50 economy class seats. Almost immediately, the planes, stripped off their trappings, went into service as Jet Airways Konnect (later JetKonnect). The new brand was Naresh Goyal’s reluctant answer to domestic Indian low-cost carriers (LCCs) that were eating up his lunch.

In the ramp-up from 2008 to 2013, JetKonnect became the workhorse as plane after plane was converted from the airline’s full-service fleet. All this, without any drum rolls or fanfare, which is Goyal’s trademark style. Towards the end of 2013, only a few aircraft continued to operate under the traditional Jet Airways branding, which offered passengers full-service at higher fares.

As has been much-documented, Goyal’s low-cost foray, or rather his version of an LCC, failed miserably. Traditional LCCs such as AirAsia have fewer staff, no frills, efficient online booking services and a system where passengers have to pay for any extra service.

But Jet’s founder-chairman’s version was to take a full-service carrier (FSC), remove the J-class and stop serving free food. Everything else, including infrastructure and staff salaries, remained the same. The extra seating did not bring in passengers by the bus-load pulling out the food did little to save cost and, instead, lost him a lot of goodwill. No airline around the world has been able to pull off an LCC without significantly reducing other costs. (Forbes India had written about Jet’s attempt to do so in its June 2009 issue, in a story titled ‘A disKonnect with J-class’.)

Jet’s domestic operations began to pull down its financial performance, and the airline ceded ground to IndiGo and SpiceJet as even loyal customers began turning away from the once popular carrier.

Travel and ticketing agents, too, were frustrated by this half-baked low-cost model. Blue Star Air Travel Services, one of Mumbai’s biggest air-ticket consolidators, has been on Jet’s list of top agents for over two decades. But its proprietor Madhav Oza says the carrier’s LCC brand was an eyewash and never helped the airline. JetKonnect did not even have online bookings. “How could it be an LCC?” he asks.

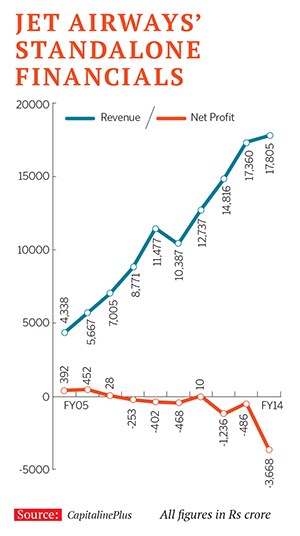

By 2013, survival was a struggle, and Jet was borrowing even for working capital. In FY14, it notched up a loss of $680 million, arguably the highest for an operating company in corporate India that year. At the same time, its debt rose to almost $1.6 billion. In August, a few weeks before credit rating agency ICRA downgraded the company’s debt to a ‘D’, which denotes a default or expected-to-default status, Goyal admitted at a press conference that his low-cost model had failed to work.

Goyal may be down, but he’s not out. The wily entrepreneur who started his journey from humble beginnings in Sangrur, Punjab, is not about to give up. With Etihad Airways, the deep-pocketed flag carrier of the United Arab Emirates, acquiring a 24 percent stake in the company—the deal was finalised last year—he is hoping to pull a rabbit out of the proverbial hat. He has already begun to reverse Jet’s course, and this time, in a very public way.

The 64-year-old chairman has given the airline four months to go back to its original two-class, full-service format, and three years to return to profitability. “We will take swift action to re-emerge as India’s most preferred airline. By December, Jet Airways will be one consistent, predictable, full-service brand,’’ he said at a press conference held in Mumbai in August.

But if the journey from a full service carrier to an LCC was such a disaster, will the trudge back to the original model be more successful? After all, wasn’t Goyal forced to launch an LCC because no one was willing to pay extra to fly Jet Airways?

Business history has many cases of nimble entrepreneurs who don’t shy away from making course corrections. But a 180-degree turn that Jet is trying to manoeuvre is rare, even in the airline business where carriers are struggling to keep their heads above water. Yet, industry experts and analysts that Forbes India spoke to say Goyal has a fighting chance of making it work this time.

One of the main reasons for this optimism is Arab wealth in the form of Etihad Airways. The Indian government’s approval for investment by foreign airlines in Indian carriers, which came through last year, is turning out to be a kiss of life for Jet. The FDI decision came too late for Kingfisher Airlines, but it gives Jet Airways and SpiceJet, two of the biggest loss-making private carriers, a chance to re-capitalise. (SpiceJet, too, is looking for investment from an international airline.)

Etihad poured $750 million into Jet in the last financial year, of which only $380 million was for the equity stake. The rest was to buy Jet’s landing slots, its frequent flyer programme and a low-interest loan—all to improve the airline’s financial position. More ways are being worked out to pump in much-needed funds. As mentioned earlier in the story, Jet lost $680 million last year, burning through most of this cash. But Etihad president and CEO James Hogan has promised more funds. At the press conference with Goyal, he reiterated his commitment to rebuilding Jet Airways.The Arab airline’s support is not just in the form of capital infusion. Jet will also benefit from synergies of scale on the entire gamut of procurement. Late last year, Etihad signed multiple deals with aircraft and equipment manufacturers to acquire 199 planes and 294 engines. It announced the Abu Dhabi carrier’s plans to enter the big league. A significant part of the agreement with Airbus was that the plane deliveries, to be made over the next decade, would be fungible. Etihad can move Airbus aircraft among its equity partners, depending on who needs the plane most. The idea is to share infrastructure and resources including people, said Hogan.

KG Vishwanath, former head of commercial strategy at Jet Airways, says the turnaround will not be too difficult: “The airline was never truly a low-cost carrier. Being a full-service airline comes naturally to Jet.’’ He had quit the company last year when the senior management was revamped to make place for a new team from Etihad. (Vishwanath has teamed up with Jet’s former CEO Sudheer Raghavan and its executive director, Saroj Datta, to start an aviation consultancy firm.)

Along with capital, the other big lever is Etihad’s network. Hogan calls it the ‘Power of Nine’ referring to the carriers that form part of the equity-alliance he has been building since December 2011. Apart from Jet, other carriers in the alliance include Air Seychelles, Air Berlin, Aer Lingus and Alitalia.

If all goes according to plan, more than half of Jet’s domestic passengers will be those who use Etihad’s network while connecting to international destinations, with Abu Dhabi as the hub. Jet Airways’ tickets to its 47-city network in India will be sold by Etihad and its partners around the world. The Indian airline’s senior management led by the CEO (designate) Cramer Ball is firming up details of the plan.

The travel industry, too, is optimistic about the success of this plan. According to Blue Star’s Oza, the Jet-Etihad combine has the potential to beat Emirates’ huge hold over the Indian market. “As Etihad develops its global operations, a lot of India business can easily move to them,” says Oza. But he adds a caveat. “[This will happen] only if they invest in improving the product.’’

The current optimistic outlook will work in Jet’s favour. The airline had initiated its low-cost experiment during the 2008 downturn, which saw a noticeable migration of J-class traffic to the economy class. This was a global phenomenon fuelled by businesses and corporations changing their travel policies. Even senior executives had to travel in the back of the bus for flights that were less than four hours long because business class fares had become untenable. Airlines often charged four to five times that of economy rates.

In India, much of the business traffic was captured by IndiGo (launched in 2006) and SpiceJet (2005). Both carriers had stepped in with a growing network of airports and offered reliable options to frequent fliers.

With the economy looking up, and companies willing to increase their spending, Jet is perhaps re-entering the full-service sector at an opportune time. The big boost for airlines this year has come from falling oil prices (crude oil is down to below $100/bbl compared to about $130/bbl in 2008). Aviation analyst and commentator Kapil Kaul says this new optimism can help Jet Airways win back some of its business class clientele. In Goyal’s new scheme, Jet’s narrow-body Boeing fleet will be configured uniformly. All the planes will have 168 seats (12 in business class and 156 in the economy section). “Filling these should not be a problem once the service starts improving,’’ says Kaul.

Within Jet Airways, the push for change has already begun. Senior employees see it as their only shot at survival. They say that Goyal has started a full review of the service delivery. “We lost a lot of customers due to a decline in service. Much of this was because we simply didn’t have the money. Resources were pulled out of almost every part of the business because of the losses,’’ a senior vice president at the company said.

Jet’s former customers complain that not only did service decline, but so did its on-time performance and reliability. Goyal has promised that the airline will return to its former ‘Swiss-clock’ timings. “We set world standards in service, we know how to do it,’’ he said.

It won’t be easy to win back trust, but Jet is overhauling its system at almost every customer-contact point from hot in-flight meals to more efficient call-centre response. The big carrot for its core constituency, frequent flyers, is more redeemable miles. Customers earning points on credit cards for all kinds of billings will also be offered miles on Etihad’s international routes. Goyal is in a hurry to launch the improved frequent flier miles programme, and with good reason, too. The newest challenge on the block, the Tata-Singapore Airlines combine, is set to announce the launch of a new carrier, Vistara (expected to launch by the end of the year). The new airline is positioned exactly in the same niche that Jet Airways wants to reoccupy.

Goyal was forced to learn some tough lessons in the recent past. Now, the entrepreneur is returning to the kind of service that made his airline a favourite in India. His future, and that of Jet Airways, depends entirely on how well this tactic works.

First Published: Sep 09, 2014, 07:19

Subscribe Now