Industry sceptical about government push for electric vehicles

Can subsidies alone power India's push to electric vehicles?

The lack of adequate charging infrastructure adds to range anxiety of EV owners

The lack of adequate charging infrastructure adds to range anxiety of EV owners

Leapfrogging technologies can be problematic—eliminating intermediate steps often results in messy policy and slower adoption. It’s a problem electric vehicle (EV) makers and consumers globally have grappled with. While some governments have intervened, like China’s, most have let market forces play, waiting for battery prices to fall and an ecosystem to develop.India has believed that throwing money at the problem will result in faster (and superior) results. It hasn’t worked so far.

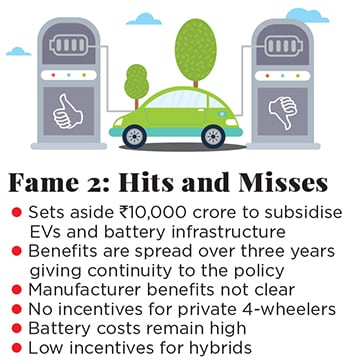

In early March the government announced a significant increase in the support given to EVs. Under Fame 2 [Faster Adoption and Manufacture of (Hybrid &) Electric Vehicles] scheme the Department of Heavy Industry laid out a ₹10,000-crore, three-year plan to incentivise vehicle owners and battery makers, with ₹8,596 crore as subsidies to owners, up from the ₹795 crore allocated under Fame 1 in 2015.

Fledgling EV makers have supported the move. “There are a lot of learnings from the previous policy that have been incorporated here," says Mahesh Babu, CEO, Mahindra Electric, who says Fame 1 received a tepid response primarily because it was announced for a year and carmakers were unsure about its longevity. However, a large carmaker says, “The previous policy did not kick-start anything. This is only an extension of that policy and doesn’t alter our plans."

Industry watchers question the wisdom of the new incentives for three reasons. First, the technology is still not quite there. People buying EVs still suffer from range anxiety, and charging stations that are few and far between do not help. Fame 2 does little to address this, by allocating only ₹1,000 crore for charging infrastructure. Chetan Maini, vice chairman of Sun Mobility, which is working on developing a network of battery swapping stations, says it is very important for the government to be technology agnostic. For now the government is moving in one direction, of subsidising battery ownership. But it would be worthwhile to look at ways to amortise battery cost so that owners are not saddled with upfront costs, and offer subsidies on everything from charging stations to infrastructure for battery swapping. For now the policy is silent on this. In February, Sun Mobility set up four battery swapping stations in Delhi and Gurugram, with a capacity to swap up to 800 batteries a day.

Chetan Maini, vice chairman of Sun Mobility, which is working on developing a network of battery swapping stations, says it is very important for the government to be technology agnostic. For now the government is moving in one direction, of subsidising battery ownership. But it would be worthwhile to look at ways to amortise battery cost so that owners are not saddled with upfront costs, and offer subsidies on everything from charging stations to infrastructure for battery swapping. For now the policy is silent on this. In February, Sun Mobility set up four battery swapping stations in Delhi and Gurugram, with a capacity to swap up to 800 batteries a day.

Second, the need for subsidies shows the technology is still far from cost effective. While battery costs have fallen in the last five years from $1,000 per kWh to $180-200 per kWh, they are still twice the price that will make them cost effective. “While there have been incentives announced for vehicles, battery costs have not fallen significantly and there is no demand visibility for localisation of critical components. This has a bearing on making the total cost of EVs higher," says CV Raman, senior executive director (engineering), Maruti Suzuki.

There is no subsidy for imported battery kits. While the government talks about setting up a component ecosystem for EV makers, there has been little action. Make in India and the government will incentivise, but in the absence of volumes it remains to be seen if any component maker takes that leap of faith.

What’s important is that consumers have taken to EVs in areas where they make economic sense. Over 95 percent of the 2,67,014 subsidised EVs sold under Fame 1 were two-wheelers owners can charge them at home and use them for an average of 30 km a day. But, when it comes to cars, there has been little demand.

Unlike Fame 1, Fame 2 has ended subsidies for private cars, and kept it only for taxis. The logic: Taxis run six times more than private cars and the subsidy is better directed towards them. However, as an industry veteran says, “Small taxis are available for say ₹5 lakh. An EV taxi is closer to ₹10 lakh. Even with the ₹1.5 lakh subsidy, I doubt there will be many takers."

Even under Fame 1, the subsidy was not enough to attract private car buyers or encourage the use and manufacture of EVs. Energy Efficiency Services Ltd, a government body that ordered 10,000 vehicles for government employees, has received fewer than 2,000. A second tender was scrapped. Babu pins it on an aggressive timeline and denies reports that it was because of the cars’ quality.

[qt]There is no demand visibility for localisation of components. This hasa bearing on making EVs cost more."

CV RAman, sr executive director (engineering), Maruti Suzuki[/qt]

Third, 59.7 percent of electricity in India comes from coal, according to the Central Electricity Authority. So, in effect, we’re trading one kind of pollution for another. Moreover, with lithium and cobalt available only in Latin America and Africa, and with a lot of supply controlled by China, India would be swapping one kind of energy dependency for another.

In its push for an electric future the government has clearly forgotten the intervening steps (hybrid and CNG vehicles) that carmakers could take if provided the right direction. The introduction of Goods and Services Tax (GST) put a higher 43 percent tax rate on hybrid cars, making them too expensive. Industry watchers also add that carmakers were gaming the system by selling mild or micro hybrids and claiming incentives. Under Fame 2 only ₹15,000 per car would be provided for strong hybrids with batteries of 1.5 kWh. Both Toyota and Honda sell strong hybrids in India, and declined to answer questions. Since the introduction of GST both companies have seen sales slow to a trickle. According to industry sources, Honda does not even have enough orders to regularly import consignments from Japan.

For now, no one is holding their breath on the mass adoption of EVs in the next five years. Maruti believes CNG is cleaner and cost effective. The Ministry of Petroleum and Natural Gas has said that it plans to expand the number of CNG pumps from 1,500 to 10,000 over the next eight years, which means a likely rise in adoption of CNG cars as people wait for the EV ecosystem to develop.

Though Babu of Mahindra Electric says he is working on getting his cars certified by the Automotive Research Association of India, to claim Fame 2 incentives, he didn’t specify how many cars they hope to sell. Large carmakers like Maruti, Honda and Toyota have made no change to their plans to introduce EVs. They’ve all made past statements saying they plan to introduce at least one electric model in 2020-22. They’re rightly cautious. At the present cost price, selling them will be a slow uphill grind.

First Published: Apr 02, 2019, 07:37

Subscribe Now