How Motherson Sumi Became a Giant Auto Parts Manufacturer

From a non-descript business, Vivek Chand Sehgal has set up one of the top automotive parts companies in the world

Vivek Chand Sehgal, 56, runs a crazy schedule. He travels almost 300 days in a year. We met him at the Motherson Sumi’s corporate office in Noida, where he’d driven down straight after landing in Delhi that morning. He told us he’ll be in town for a couple of days before leaving for Australia. Sehgal is an Australian citizen. A day ago, he was in Chennai meeting some customers. The week before, he was in Germany meeting some of his other customers. That’s how far back he can remember. “After some time, you stop counting,” he says.

With a lifestyle like this, you would expect Sehgal to complain of jetlag. But there’s none of it. He says the secret lies in sleeping well. Nevertheless, if the schedule does get to him, all he needs is a cup of truckers’ tea—lots of milk, lots of sugar and lots of ginger. “For the next three hours, your headlights are on. Bright! You should have one,” he adds.

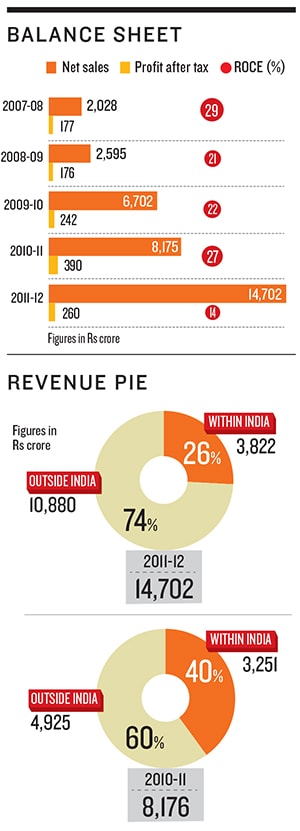

We did. But while the tea was good, it wasn’t essential. The growth story of Motherson Sumi is interesting enough to draw attention. Motherson’s turnover has grown from Rs 10 crore in 1993 to about Rs 14,702 crore in 2011-12. In 1999, Maruti Suzuki, India’s largest car manufacturer, accounted for almost 80 percent of Motherson Sumi’s total business. Today, Motherson has spread to 25 countries with 124 plants. And 76 percent of the company’s business now comes from outside India. The company’s stock price outperformed the Sensex almost five times in the last year.

Add to this, in the last decade, Motherson made nine acquisitions. “Whenever we made such projections, the analysts were laughing. No company can grow 10 times in five years. Well, here we are and we have our projections ready for the next five years,” says Sehgal.

With the birth of Maruti Udyog in 1983, several auto component manufacturers came into existence in India. Almost everyone started with a technology collaboration or joint venture with a Japanese counterpart. As multinationals started coming in, new collaborations were formed with either American or German companies.

But while most of its peers were content with their India business, Motherson Sumi went global with gusto. The only Indian company that comes close is Bharat Forge, one of the largest forgings companies in the world. “Our exports in 2000 were less than $10,000 a year. Then we thought of a policy called 3CX15. Which means no commodity, no country and no company should constitute more than 15 percent of our turnover,” says Sehgal.

Several component companies, who stick to a particular manufacturer or a market, go through a rough time when the industry goes through a rough patch. The only way to beat it is to diversify your risk to several geographies across multiple manufacturers.

Motherson has followed this to the T. Today, Samvardhana Motherson Group (SMG is the holding company with nine business divisions) is one of the world’s largest manufacturers of wiring harness, mirrors and cockpits (plastic parts), among other products. “The Daimler Benz C, E and S class cockpits and instrument panels are all done by Motherson,” says Sehgal.

The financial world has taken note of Motherson’s rise. A fund manager who has followed the company says Motherson has three big trends in its favour.

“One is that the company’s content per car is increasing. Second, the Indian market is moving towards bigger cars, which means more electronics. So we see an upside for its wiring harness business. Finally, exports out of India by global manufacturers like Hyundai and Nissan are on the rise. We see Motherson’s products getting in those,” he said.

It is another matter altogether that Motherson Sumi wasn’t set up to become an automotive components company. It was a company started by Sehgal and his mother with a small but important purpose in mind. To save taxes from the Government of India.  Mother and Son

Mother and Son

Sehgal’s maternal grandfather was a jeweller, who believed Sehgal was up to no good in college. So he offered him a job. In 1975, the government had allowed the export of silver bullion. “He told me that all I had to do is to pick up silver from Chandni Chowk, take it to the airport, get it stamped by the customs and give the documents to the state trading corporation. They were the ones exporting on behalf of my grandfather,” says Sehgal. His remuneration—Re 1 per kilogramme, which would translate into Rs 1,000-Rs 1,500 a month.

Then, Hunt Brothers, one of the richest families in the USA, started to corner the silver market around the world and prices soared. “Instead of selling 1-1.5 tonnes of silver a month, he started selling 1-2 tonnes a day. I was now making Rs 2,000 a day and needed a company because individually I would have to pay tax worth 90 percent of my earnings,” adds Sehgal. That’s how Motherson started.

Over the next few years, Sehgal dabbled in various businesses like selling house cables and polyester chips. It was in 1983 that someone asked him if he would be interested in making cables for a car that Maruti Udyog was planning to build. “Because automotive wires are similar to house wiring, I said why not,” he says. A Sikh gentleman was interviewing prospective vendors. He asked Sehgal what set him apart from the 300-odd people waiting outside. Sehgal just told him, “Give me a chance.”

That chance came in the form of a plebian car connector. Sehgal was asked to come back with samples of his own to prove that he could do the job. Sehgal approached a friend who used to make speakers and had a mechanic who was good at making plastic parts. “I told this guy what I wanted. He asked me to come back after two weeks. I told him I want it now. He then asked me to come at 9 pm with two quarters (of whiskey). He said I’ll sit down with you and as long as you are there with me, I will keep working on it,” adds Sehgal.

At 10.30 next morning, Sehgal had about 25 pieces of the connector. He went straight to Maruti. “I put one in front of the Sikh gentleman. He said, ‘You give up? Can’t do it?’ I put another five on the table. He asked me whether I got it from the market. Then, I put the rest on the table and asked him to spot the original piece. He picked one up, but I told him he was wrong. Actually, the real piece was in my left pocket,” says Sehgal.

But he still had some way to go before he could convince the gentleman that he had made 25 connectors overnight. That’s when Sehgal showed him the mould into which another piece of connector was still fitted. “The gentleman then took me straight to the engineering chief and told him that here is the guy who is going to make the wiring harness,” Sehgal said. Four days later, he was in Japan, coaxing the officers of Tokai Electric to do a joint venture. Even though he ended up with just a technology collaboration, it was a good start.

Acquisition Spree

Acquisition Spree

With nine acquisitions in the last decade, Motherson has built a reputation that it is always hungry for distressed assets. Pankaj K Mital, chief operating officer, disputes this. “Motherson does not go after any asset. We wait for the customer to come and tell us that he needs help to turn a particular asset around. After that we study whether it is possible,” he says. Take for instance Motherson’s acquisition of Visiocorp, the UK-based exterior and interior mirror manufacturing company, which used to supply to companies like BMW, Volkswagen, Daimler and Jaguar Land Rover.

Visiocorp had been Motherson’s collaborator for close to 13 years. “When this company went belly up in 2008, carmakers Daimler, Volkswagen and BMW asked us if we could take them over. That was a tough call. Motherson and Visiocorp were of the same size. And this company was in 17 countries. But the carmakers promised they’ll help us,” says Sehgal. And they did. For a company, which had a top line of 500 euros, Motherson paid 19 million euros and the carmakers paid about 25 to 30 million euros. “And it was debt free, tax free…Today, it is sitting with a top line of 900 million euros,” adds Sehgal.

Sehgal stands out in his modus operandi, too. He believes this success would not have been possible if he was still the managing director. When you are in an operational role, Sehgal says, it consumes you. In 1995, he had given up the MD’s position to become the vice chairman. “I said, if we are going to grow to Rs 100 crore, I can’t do it myself. I need the best of professionals. From 1987 to 1993, every time I came back from a Japan trip, I saw the company was doing better than when I had left. That’s when I realised that most of us suffocate our own companies. Because we tend to overprotect,” he adds.

Today, Sehgal spends most of his time meeting customers and employees across the world. “I don’t do operational meetings. People call me only when there is something they can’t handle,” says Sehgal.

Isn’t it strange then that his son Laksh Vaaman Sehgal is the CEO of Samvardhana Motherson Reflectec, a subsidiary of SMG? Sehgal says that’s because of a technical problem. In Germany, the CEO of a company can file for bankruptcy without referring to the shareholders. “In 2009, post Lehman, it was a very tough time and the only person I could think of who would not file for bankruptcy is my son. He is just 29. So he will be here for some more time but after that he will also withdraw. Just like me,” he adds.

Father and Son

While Sehgal senior has laid out the diversification strategy and made the right acquisitions, the company now has to go down the value path. For a company with almost Rs 14,702 crore turnover, its profits are a measly Rs 259 crore. The pressure of the acquisitions is clearly visible on Motherson’s financials. Its ROCE (return on capital employed is a ratio that indicates the efficiency and profitability of a company’s capital investments) dropped significantly from 27 percent in 2010-11 to 14 percent in 2011-12. Profits, too, dropped 34 percent over the same period.

Motherson’s other big challenge is competition on the global stage. Especially, in the new businesses it has ventured into.

Vaaman, a graduate of Columbia Business School, is shy. But he has in him a sense of where he would like to take the company. “When we acquired Visiocorp, we knew the process of manufacturing mirrors but we also knew that this company has quite a few technologies that are key to our future growth. They might not be in use in India right now. But I think it has more than 400 patents today. And for us that’s where the future is,” says Vaaman.

First Published: Feb 13, 2013, 06:36

Subscribe Now