Finally, it was the software that let him down. After years of fist-clenching and hand-wringing, heated negotiations and political manoeuvring, Barack Obama launched his health insurance exchanges in the US early last October. Healthcare.gov, the US federal website, was supposed to make insurance buying easy. It didn’t. Software glitches seemed to plague the system.

Thousands of users were disappointed. The American tech company behind the website was shamed. Critics wagged their fingers and said ‘we told you so’. An Indian business newspaper even suggested Infosys should volunteer to clean up the project at no cost to earn some goodwill from the Americans.

But the alarm bells didn’t ring as loud for software engineers whose war chronicles almost always revolve around embarrassing software glitches. For them, this was just another story that attracted attention only because it involved one of the most ambitious projects of a most powerful man. Consider this. According to a 1992 estimate by researchers, Microsoft’s software has only one defect per 2,000 lines of code at the time of release. Yet, its reputation for buggy software can be explained by the fact that Windows 7 has over 40 million lines of code.

Fact: You can’t escape software bugs. And some bugs can be more devastating than others. In 2012, a software glitch cost Knight Capital $460 million a few months later, the once promising company was sold off. This only underscored a 2002 study by National Institute of Standards and Technology, which estimated that software bugs cost the US economy $60 billion a year. “Those who live by software”, a joke among the techies goes, “will die by software”.

These are such anecdotes, numbers and wisecracks that once gave independent software testing companies a place of prominence in the Indian IT sector. Around a decade ago, year-on-year growth of 40 percent seemed to be a given, a former senior executive from RelQ, an independent software testing firm, says. A few years later, RelQ was acquired by American IT equipment and services company EDS. Applabs, its bigger rival, was even more confident about independent testing. Once when a journalist questioned the viability of pureplay software testing companies, Sashi Reddi, its CEO, pointed to the acquisitions made by Applabs. Just a year on, it was acquired by CSC.

It’s not just RelQ and Applabs. Several other Indian software testing firms that hoped to make a huge impact as pureplay testing companies either folded up or lost their identity after being acquired by IT services firms.

Take Thinksoft, which was acquired by German software testing company SQS in November 2013. Asvini Kumar, the founder, says one of the reasons he decided to sell his stake to SQS was because it was also a software testing firm, emphasising that there continued to be a large scope for pureplay testing companies. However, the message from the market was different—Thinksoft had been consistently trading at a fourth of its price prior to the announcement. (Asvini Kumar has since stepped down as Thinksoft’s managing director.)

But there is one company that still believes it’s possible to be a pureplay testing/assurance company—and also to scale up as one: Maveric Systems. What are they smoking?

![mg_74998_maveric_systems_280x210.jpg mg_74998_maveric_systems_280x210.jpg]() The founders of Maveric—Ranga Reddy, P Venkatesh, NN Subramanian and VN Mahesh—are professionals with significant experience in consulting they had no intention of setting up a software testing firm. The plan was to help and invest in companies that showed great promise. This was in 2000, when the exuberance in the technology market was still being justified as rational.

The founders of Maveric—Ranga Reddy, P Venkatesh, NN Subramanian and VN Mahesh—are professionals with significant experience in consulting they had no intention of setting up a software testing firm. The plan was to help and invest in companies that showed great promise. This was in 2000, when the exuberance in the technology market was still being justified as rational.

The tagline of Maveric was ‘catalysing business’ and it had invested in a handful of companies—across e-learning, voice recognition and entertainment verticals—that promised to do well in the dotcom era. Nine months into the game, the bubble burst, taking several new startups down with it.

The founders considered going back to their old jobs for a while. But then they figured that they made a good team. They liked working with each other. “So we decided to work together,” says Subramanian, popularly known as Subbu, a director at Maveric.

They scouted for business by offering their skills—techno-functional is how how Subbu puts it—to friends and associates around Chennai, slowly getting a sense of the big wave that was just gathering strength. The time between the late 1990s and the early 2000s was interesting for outsourcing—and for Chennai. Technology offerings were getting more diverse and complex as clients made investments across functions. Suddenly it was about making several applications work together. Banks such as Standard Chartered and Citigroup were setting up subsidiaries in Chennai to take up the back-end processes and software development. Maveric landed its first projects to test software applications and, soon enough, they figured out where the future of their firm lay. They then let go of other projects to focus only on testing.

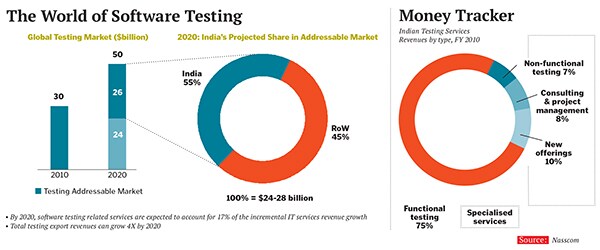

Maveric was not the only company to appreciate the sizeable market for independent software testing. Applabs, Thinksoft and RelQ were also getting customers as fast—if not faster—than Maveric. Soon, other small- and mid-tier companies, which were primarily into IT services, started bidding for projects. In India, testing as a sub-segment was growing faster than traditional IT services even globally, while traditional outsourcing grew at 3 percent, testing services were expanding in high single digits. That was when the big boys descended—the likes of TCS, Infosys, Cognizant and Wipro.

What followed was inevitable. The software testing business was no longer niche—it became completely mainstream by 2006-07. If the IBM-Airtel deal is the high point of the domestic software story, ABN Amro giving a large software assurance contract worth $200 million to TCS, Infosys and Patni was the software testing equivalent.

By this time, many companies started positioning testing as a separate practice research firms were publishing reports on the subject, analysts had started reserving some questions on testing and the big companies were recruiting in droves. For example, Cognizant’s testing practice was several times bigger than the largest pureplay testing company of that time—Applabs.

Consolidation followed. “Everything the small independent software testing companies said they had, we had. And we had in much greater numbers. What we didn’t have we could always acquire. They were getting crushed under our weight,” a senior executive from a top IT services company says.

In this scenario, what makes the Maveric founders bullish?

Commitment, for one. CEO of human resources consulting firm Grow Talent Anil Sachdev, who recruited two of the co-founders—Reddy and Subbu—while he was running Eicher Consulting, has now known them for about 25 years, mentoring and advising the founders through their journey. “I had a consulting firm. I sold it because early on I had decided I will focus on education once I turn 50,” says Sachdev who later founded the School of Inspired Leadership, based in Gurgaon. “Ranga and his team are still young, and as far as I know they have no other vision than building Maveric,” he points out.

And they have their eye firmly on the evolution of the industry. Reddy and his team believe that the testing market is undergoing a change similar to the one they saw when they founded Maveric—around the scope of what independent software testing firms set out to do. A couple of years ago, consulting firm McKinsey studied why IT projects fail and the findings were instructive. For instance, they found that on average, large IT projects run 45 percent over budget, 7 percent overtime and deliver 56 percent less value than predicted. Moreover, there were cost overruns primarily because of unclear objectives. In other words, there is an increasing realisation that the most important issues in an IT project relate not so much to the bugs in the code as to the business case.

Reddy believes that Maveric took the right calls early on, a factor that will help the company ride this wave. “Many software testing companies focussed on the technology but we were focussed on domains right from the beginning,” he says. For nearly 10 years, Maveric stuck to the banking and insurance domains, and has recently moved to telecom. Also, many of its competitors target testing related to maintenance projects rather than transformational projects, which were of shorter duration and had choppy revenues. However, focusing on both has helped Maveric develop expertise in what a software application should do, and how it should be built.

In the last two years, its primary pitch has gone beyond testing applications—it will also provide what it calls requirement assurance, programme assurance and application assurance. In other words, it will work with clients and software vendors from the time they decide on requirements till the project is signed off. This could mean getting the clients and vendors to even agree with the sequence of release.

For example, while working with a banking client, Maveric insisted that a module relating to trade finance be completed in the first phase of the project rather than in the final. The vendor and the client reluctantly agreed but Maveric was proven right when the test results came out. These insights emerge from a focus on business and domain, rather than just technology, says Reddy.

This approach has started showing results. First, it has found its deal size increasing. From a typical $700,000 to $1 million, its typical project size is now up to $2.5 million to $4 million—and this because of the broader scope. The billing rates have gone up too. Revenue per employee, a key metric for IT services firms, has gone up by nearly 20 percent to Rs 22 lakh per employee a year. More importantly, it has made inroads into a couple of Tier 1 banks in Europe. This will help Maveric grow from Rs 120 crore in revenues at present to Rs 500 crore in the next five years.

Reddy believes that the key to Maveric’s future growth is marketing. “We primarily grew thanks to word of mouth. However, for the next phase of growth we need focus on marketing,” he says.

But there are some who say it will need more than that. It will have to fight against the same forces that other pureplay testing companies faced a few years ago. Several IT companies have ramped up their consulting divisions, and they are getting better at handling complex processes. The earlier set of pureplay companies had to fight the scale of IT services firms. Now, they have to fight the breadth as well.

The founders of Maveric—Ranga Reddy, P Venkatesh, NN Subramanian and VN Mahesh—are professionals with significant experience in consulting they had no intention of setting up a software testing firm. The plan was to help and invest in companies that showed great promise. This was in 2000, when the exuberance in the technology market was still being justified as rational.

The founders of Maveric—Ranga Reddy, P Venkatesh, NN Subramanian and VN Mahesh—are professionals with significant experience in consulting they had no intention of setting up a software testing firm. The plan was to help and invest in companies that showed great promise. This was in 2000, when the exuberance in the technology market was still being justified as rational.