How Loney Antony cracked the payments market

How ATM industry veteran Loney Antony successfully turned entrepreneur with a disruptive outsourcing model

Loney Antony, founder and MD of Prizm Payments, has a peculiar gift hanging on his office wall at the company headquarters in Goregaon, Mumbai. When Prizm was acquired for $250 million by Hitachi in November 2013, one of his exiting investors (venture capital giant Sequoia) presented him with a glass frame containing four ties, each cut in half. Each tie represents one of the four founders at Prizm, symbolising how the 40-somethings had gone from tie-and-jacket professionals to successful entrepreneurs.

Seven years after co-founding Prizm Payments, an ATM-outsourcing company, with industry veterans Shyam Sunder, Jayant D’Mello and Raghu Nathan, Antony, 52, is unapologetic about wearing a suit every day. “Sequoia wasn’t used to entrepreneurs who are always wearing suits. Even today, the industry we face is very formal,” he says. “If I have to meet GMs of banks, they’re always in suits. So you can’t be selling to them in jeans. When in Rome…”

A trained chartered accountant from Kochi, Antony began in the ATM business in 1994 with NCR Corporation, the world’s largest ATM-maker, where he met his Prizm co-founders. Today, he is a respected pioneer in the ATM industry, with Prizm’s revenues currently standing at Rs 800 crore. “If there is a Bharat Ratna for ATM-led solutions, it is [for] Loney Antony,” says Uttam Nayak, global head of digital payments for emerging markets at Visa. Nayak has known and worked with Antony since the mid-1990s. “He is the man who has grown the ATM industry in India by handholding the banks.”

“If I look back at the last 20 years, every two or three years, there’s been something disruptive. It keeps you on your toes,” says Antony, on what’s kept him hungry.

Leveraging changing technology is the reason why Prizm has been successful: And Antony is now looking to leverage new technology from Hitachi (like cash recycling machines: ATMs that can accept cash deposits and dispense the same notes to other users) to deploy ATMs in rural India.

Transaction history

When automated teller machines started making an appearance in the country in the late 1980s, banks were operating their own ATMs. By 2002, ATM-outsourcing companies began to manage the machines on behalf of the banks, who would then pay a fixed fee and gain from operational and cost efficiencies, like any outsourcing partnership. The banks would ask for ATMs to be set up in a specific locality Antony would then send agents to look for a venue and install an ATM.

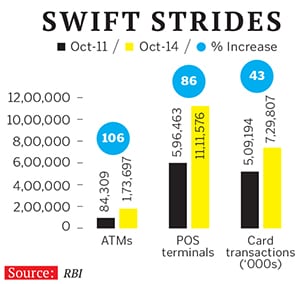

However, regardless of the growth in the number of ATMs in India (see graphic), Prizm figured out that some ATMs would attract more transactions than others because of their locations. “Loney and his co-founders saw an opportunity where others saw a problem. India had a lot of debit cards but not enough ATMs to use them at. Hence, the long queues at ATMs,” says Mohit Bhatnagar, managing director, Sequoia Capital. “They sensed that if they create a large ATM estate and pioneer a new business model that allowed Prizm to get paid every time an ATM transaction took place, there could be a valuable company created.”

By introducing this transaction-based model (banks pay Prizm per transaction instead of a fixed monthly fee) in 2008 and using analytics to determine where to position ATMs for maximum throughput, Prizm began to pull in a disproportionately high number of daily transactions and, thus, higher revenue.

“We collect data from the banks to find the right location,” says Antony. By tweaking the model, Prizm took the task of scouting for venues upon itself. And the strategy has worked: Prizm grew to $100 million (Rs 600 crore) in revenues in just four years.

“[Prizm’s] key differentiator is that it can analyse bank-, market-, and industry data and recommend suitable sites for ATM deployment to create brand presence in locations that financial institutions desire,” says a Hitachi spokesperson via email.

Account statement

Prizm employs 1,200 people in India and their quiet, staid Mumbai office is not the usual colourful environment most tech startups strive to create. In fact, Prizm comes across as much as an industry veteran as its founders. This might be because it is not the first time Antony has built a company from scratch, it’s the third. In the first two instances, he did it for someone else. Antony was part of the founding team of NCR India in 1994 he spent three years as CFO and five more as country manager and CEO, growing from a team of four people to 2,000 employees and revenues of Rs 1,100 crore.

While NCR was into building ATMs (products), Antony wanted to get into managing ATMs (services) and joined Euronet India as part of its founding team in 2002. “We built a successful platform in India for ATM outsourcing and shared networks called Cashnet. For the first time, customers could use ATMs of banks in which they did not have accounts,” says Antony. “Once Cashnet became popular, the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) said we should create one for the country and that became the National Financial Switch, built by Euronet on behalf of RBI.”

The business expanded into Indonesia, China, Bangladesh and the Middle East with Euronet growing to Rs 300 crore in revenues by 2007. But Antony felt there was more scope for growth within India and, in 2007, proposed a management buyout, backed by private equity players like Sequoia. The buyout did not fructify.

It was a setback for Antony. Sequoia’s Mohit Bhatnagar, who has known Antony since 2004, seized the opportunity. He says, “When Sequoia decided to back Loney and his co-founders’s dream of building an independent ATM company, many folks thought it would not work: Forty-five-year-old entrepreneurs, an asset-heavy business model in a heavily regulated industry? ‘What were we thinking?’ they asked.” Consider that 2008 was possibly the most challenging time to set up a financial services company. “The first 18 months were traumatic to say the least,” says Antony. “No deals were happening as the banks had gone into a freeze because of the financial crisis.”

After a slow start, the inflection point came in April 2010 when Axis Bank placed an order for 3,500 ATMs. Axis had built a network of 4,000 ATMs over 14 years and Prizm was asked to double the number in 18 months. Axis also took an undisclosed minority stake in Prizm and exited along with Sequoia and Winvest Holdings during the Hitachi acquisition last year.

“When you’re dealing with lakhs of daily transactions, you need to have faith in the vendor and Prizm provided us with the comfort through Loney and his experienced team,” says V Srinivasan, executive director, corporate banking, Axis Bank. “Loney had the vision to think big and work with partners to build scale.”Antony says Prizm manages 30,000 of India’s 1.85 lakh ATMs, along with 1.6 lakh of the 10 lakh point-of-sale terminals (hand-held machines used to swipe credit and debit cards). While this gives them 15 to 17 percent of the total market share, he says they have a 25 to 30 percent share of the outsourced market (official statistics are hard to come by since most players are unlisted).

Mumbai-based AGS Transact Technologies Ltd. earned revenues of more than Rs 640 crore from its ATM business in FY14, Chennai-based Financial Software & Systems (FSS) Rs 600 crore, US-based Euronet India about Rs 400 crore, and Tata Communications Payment Solutions Limited (TCPSL) generated Rs 473.7 crore. AGS (also contracted for the 2010 Axis Bank order) has plans of going in for an IPO soon, while TCPSL has seen revenues grow tenfold in four years.

Although competition is fierce, Antony is respected by his peers. “If you ask me to point out the smartest CEO in the industry, it would be Antony,” says Sunil Udupa, who has been in the industry since 1987, and currently heads Mumbai-based ATM security startup, Securens. Udupa used to head AGS, Prizm’s rival. “Though Loney and I have competed against each other forever, we are very good friends,” he says.

The market is crowded with strong players and entry barriers are low, but the opportunity is huge. World Bank estimates in 2012 said India has only 11 ATMs for 1 lakh adults, by far the lowest among the Brics countries: Russia has 182, Brazil 118, South Africa 59 and China 37. An October 2014 CII-Deloitte report says the banking sector needs to set up more than 20,000 ATMs before August 14, 2015, to meet the requirements of the Pradhan Mantri Jan-Dhan Yojana financial inclusion drive. “The RBI mandate that every public sector bank should open an ATM in every bank branch further highlights the opportunity size in India,” says a September 2014 ICICI Direct report on TCPSL.

Long-term securities

But public sector banks pose one of the three key challenges for Antony. “We didn’t get into the low-cost game like our competitors. We articulated to the banks that the partnership would mean additional revenues for them [more customers coming into their ATMs], even though cost may have been higher,” says Antony. “That made the difference for us, until PSU banks came into the picture. With PSU banks, it’s all about bidding and reverse auctions and you have to have the lowest cost.” Because Prizm bears the fixed costs and the risks of putting up ATMs, it can’t compete with low-cost rivals who charge banks a fixed fee to cover their costs, regardless of the number of transactions taking place.

Prizm knows it cannot rely on bank orders alone, and is looking to deploy its own ‘white label ATMs’ (WLAs). WLA operators set up their own ATMs, and card-issuing banks pay a fee to WLA operators every time a customer swipes their card.

The second major hurdle in the ATM business is RBI regulation that controls how much WLA operators can charge banks. In February 2012, fees were fixed at Rs 18 per cash withdrawal and Rs 8 per balance inquiry, but in August 2012, they were revised to Rs 15 and Rs 5 respectively. Prizm and TCPSL have so far installed more than 1,000 WLAs, but the 20 percent revenue loss has forced them to slow their expansion plans.

The final challenge posed by WLAs is that RBI regulations allow them to only disburse cash, and not accept cash deposits. This one-way process means the machine must be frequently replenished with cash (up to 20 times a month) and operators incur costs for secure cash transport. Prizm’s latest WLAs from Hitachi can ‘recycle’ cash: Currency notes can be deposited by one user, vetted by the ATM and disbursed to the next user. Such cash-recycling ATMs are used across the developed world because they reduce the number of trips (twice a month) needed to replenish the machine with fresh cash. Prizm, however, has not been able to install these machines due to government rules.

The current regulatory environment may not be ideal, but Antony has been around for a while and has proved his mettle. Whether he’s meeting Hitachi’s senior team in Japan or looking at rural ATMs in tier-6 locations in India, don’t expect the suit and tie to come off anytime soon.

First Published: Jan 27, 2015, 06:14

Subscribe Now