How cool! Daikin eyes Indian market using Japanese technology

Daikin, the global leader in ACs, is betting on energy efficient technology and entrepreneurial dealers to succeed in India

There is a calming diligence about a Japanese factory floor. Employees, all in identical dull grey-blue uniforms, tend to their units meticulously over the roar of the giant machines that flank them. But in a corner—under an electronic scoreboard which signals how many compressors have been made vis-à-vis how many should have been made—workers, waiting for their shift to begin, gather around a colleague’s smartphone to watch the latest Bollywood video. This may be a hi-tech Japanese factory where employees have weekly Kaizen (self-improvement) meetings, but it’s in the heart of Rajasthan. It is the only manufacturing unit of the Indian operations of Daikin Global, the $17.6 billion AC manufacturer headquartered in Osaka, Japan.

“In 2009, it used to take us one month to build an industrial chiller. Now, we can produce it in one shift,” says a factory production manager. The manufacturing plant at Neemrana, Rajasthan, plays a key role in Daikin’s plan to become a market leader in India by 2015. When the company entered India in 2000, through a joint venture with Usha Shriram Enterprises, it had decided to target the premium space, ceding market share to Korean giant LG and established Indian players such as Blue Star and Voltas who operate in the mass segment. (In 2004, Daikin India bought out Usha Shriram’s stake in the JV.)

In 2006, Daikin Global laid down a blueprint to become a world leader in the AC space, a strategy that was adopted in all the countries where it had a presence. It further cemented its aggressive plan by buying American duct-AC specialist Goodman Global for $3.7 billion in August 2012.

In India, Daikin upped its game in 2009 when it stopped importing AC units from Thailand and launched a manufacturing base at Neemrana. In the five years that the plant has been operational, Daikin has become the second-biggest AC maker, after Voltas. From 34,000 ACs and revenues of Rs 440 crore in 2009-10, it has increased its output to 400,000 units. In 2013-14, it reported a turnover of Rs 2,200 crore. This success is the result of marrying cutting-edge Japanese technology with Daikin Global’s management practices among Indian experts who understand the AC market.

“My boardroom has more than 500 years of India experience combined with Japanese DNA,” says Kanwal Jeet Jawa, managing director of Daikin India. But he acknowledges that the company is still far behind the Rs 5,244 crore market leader, Voltas. Nipping at Daikin India’s heels is LG, which reported a Rs 2,000 crore turnover in 2013-14.

Daikin has a long way to go before it topples Voltas, and 54-year-old Jawa might just be the man to make it a reality. The company got in Jawa in 2010, a year after it decided to scale up its India operations. Kanwal Jeet Jawa began his career in 1980 as a service engineer. An AC industry veteran, he’s been with Voltas (twice), Blue Star, Carrier, Godrej and Uniflair. “In India, people do business with people. I started my career as a service engineer, so I know what service delight means,” he says.

He’s enthusiastic about Daikin’s future in India. At a meeting in the factory’s boardroom, with senior employees in attendance, general manager (manufacturing) Vikas Verma recaps the company’s India business. Suddenly Jawa interrupts his power-point presentation. “He was with Carrier, he was with Voltas, he was with LG,” he says, pointing to some of the employees with his index finger. “The best collected together. The chief of O General is our south zone head. Our north head was senior GM of Voltas. Our room air-conditioner head was with LG Bahrain.”

Jawa isn’t the only weapon the Japanese company has got. Daikin has poached talent from its competitors to help steer its India operations from niche to mass market. This strategy has filtered down to even the dealership level. Jawa convinced executives employed in rival AC companies to quit their jobs and become independent dealers working exclusively for Daikin’s products. His small army of entrepreneurs includes two former vice presidents from LG and Samsung who now run dealerships in Delhi and Gurgaon, a former Schneider sales director who operates out of Faridabad for Daikin, and a dealer in Gurgaon who was a director at Carrier.

“They are the extended arms of Daikin. They book the order, I supply it. They will oversee the installation commissioning and will get a sales commission. Instead of being employed by Daikin, they build their own teams and don’t need to make a big investment in our stock,” says Jawa.

It’s a model he’s picked up from Daikin China. In 1999-2000, the Chinese market was dominated by local players. The AC manufacturer was unable to crack the existing dealership network. It circumvented this by targeting “hungry young men” who had the contacts and craved the success that entrepreneurship can bring. Jawa recounts one instance where Daikin had tapped a Chinese taxi provider who had a fleet of 500 cars. “His clients became contacts, and today he’s the biggest dealer in his region,” says Jawa.

At Rs 20,000 crore, Daikin China’s revenue is 10 times that of India’s, and the Japanese company wants to replicate its success here.

The AC business is split into multiple segments: Room or wall-mounted split air-conditioners that are sold through multi-brand retailers and dedicated dealerships Variable Refrigerant Volume (VRV) and duct ACs, which are used in commercial spaces such as offices and restaurants and chillers for large building projects like airports and shopping malls. Daikin claims it has a 12.5 percent market share in the consumer space, but industry experts estimate the figure is lower. LG and Voltas have a firm hold over Indian households, and a brand appeal that the low-key Japanese company will find tough to break.

Nearly half of Voltas’s revenues come from its growing consumer AC business. A Rs 80-100 crore advertising offensive gave the Indian company the muscle to conquer LG, which was the market leader in India between 2002 and 2012. Voltas—a Tata Group company—made a concerted effort in 2006 to change the way ACs were sold in India. It shifted from a sales and dealer model to a retail model, where ACs were marketed as consumer products rather than specialised equipment.

This is where Daikin differs from its competitors. “We are not into the typical mutli-brand retailers like Croma, Vijay Sales, etc. Maybe five percent of our turnover comes from them,” says Jawa who is not competing with Voltas and LG’s advertising spends or the breadth of their network, especially in the consumer AC segment. He’s trying to use high quality service to back young dealers with an entrepreneurial bug.

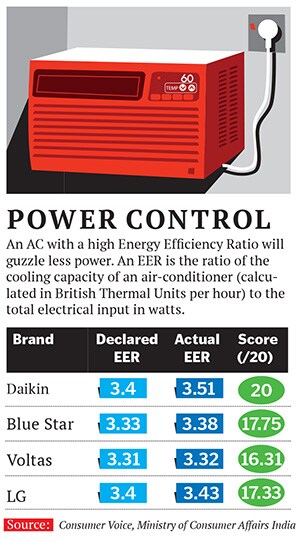

The entry-level and price sensitive market is populated by brands such as Onida, Godrej and Videocon. These are low efficiency ‘1-star’ ACs that guzzle electricity. At the other end of the spectrum is Daikin, with the highest energy efficiency.

Voltas, LG and Samsung occupy the space between, in the mid-market segment, but Daikin wants a bigger slice of the pie. It had lowered the price of its ACs, but its units still cost 15 percent more than those of its competitors. In 2009, a consumer would have had to pay Rs 50,000 for a 1.5-tonne premium Daikin AC. Today, a similar unit is priced at about Rs 35,500. The mid-market prices of its rivals start at Rs 28,000.

According to Kunal Sheth, an analyst with advisory firm Prabhudas Lilladher, Daikin will find it tough to get the number one spot in the room AC market because of its price-premium trade off. He says that if Daikin lowers its prices, it may lose the aura of technological superiority.It doesn’t help that ACs are still not as popular as televisions and phones. Over 40 million smartphones and 7 million flat-screen TVs were sold in 2013, as opposed to 3.5 million room air-conditioners. “If you look at the buying power trend in India, 70 percent of people have TVs and fridges and 55 percent have washing machines. More cars are sold than ACs,” says Jawa.

But the opportunity for growth is huge. A Natural Resources Defense Council report estimates that 116 million room AC units are expected to be in service in India by 2030.

Daikin is betting on the cost-saving efficiency of inverter-ACs to drive growth. “We show on the back of the bill that an R34 inverter uses up to 71 percent less power. This is based on the average power usage of that particular city,” says Jawa. In Japan, all the ACs that Daikin sells use power-saving inverters. In Australia, the model accounts for 85 percent of its sales, and in China, it’s more than 50 percent. “In India, it was less than five percent. But after we launched the R32 inverter last year, of the 400,000 units sold, about 25 percent were inverters.”

It is in Daikin’s interest to help customers use less electricity, especially because its distribution network targets the commercial market. The company’s patented VRV technology can calibrate the speed of the compressor to the number of people in a room. The result: A Daikin AC in a room with two people will automatically use less power.

The company can also monitor the health of a network of ACs it has sold to a client remotely, and let technicians on the ground know if there is likely to be a problem. “Daikin’s VRV installation, the biggest in the world, is in India. We have an 18,000hp installation at the EON SEZ the Pune,” says Jawa.

While Daikin has yet to crack the room-AC market in India, it claims to be a leader in the commercial segment. “In China and India we sell more VRV ACs than the next five competitors put together,” says Jawa. “If customers don’t save money, nobody will buy our units. You sell the benefits, not the features.”

Jawa tells his dealers who visit the Neemrana plant, the same thing. The workers on the floor are used to visiting dealers peering over their shoulders. If someone steps over the magnetic boundary line and into the production area, an alarm is tripped and the unit instantly stops. The factory tour ends as afternoon turns to evening and senior executives, both Japanese and Indian, get into German cars to head back to Gurgaon. They leave behind a busy factory floor, a large portion of which is actually empty—lying in wait for the market to heat up.

First Published: Jul 28, 2014, 06:01

Subscribe Now