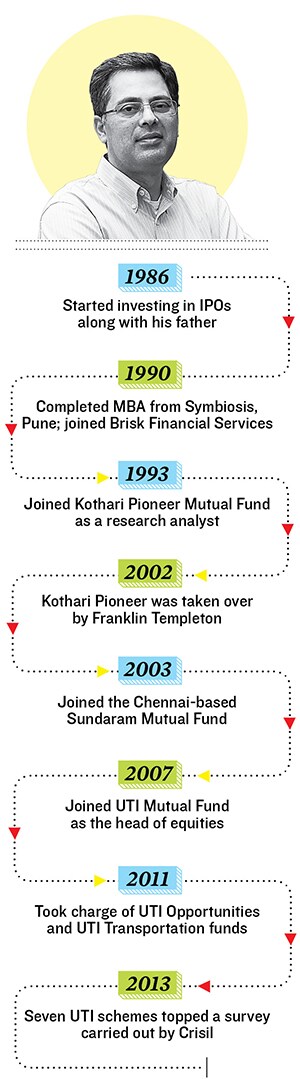

How Anoop Bhaskar Led the Rise of UTI Mutual Fund

Anoop Bhaskar weathered managerial uncertainty and weak markets to turn UTI Mutual Fund's stocks into category outperformers

Picture this scenario: You work for a public sector fund house, where stakeholders cannot agree on who should head it. You have high-level manoeuvring to nominate the relative of a key finance ministry official, which the principal strategic investor is resisting. The sector regulator is not amused, and declines to allow the fund house to launch new schemes till it appoints a boss. And finally, a temporary acting CEO is appointed just to break the logjam.

In such a climate of uncertainty, you would expect a fund manager to play safe and not do much. More certainly, you would not expect him or his funds to appear at the top of the performance table. But Anoop Bhaskar appears to have insulated himself from all the chaos around him.

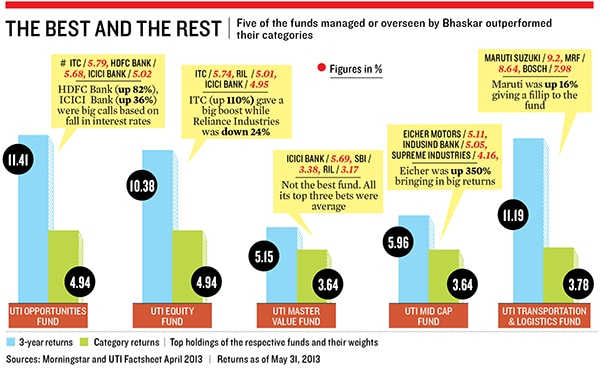

Last month, rating agency Crisil ranked UTI Mutual Fund, of which Bhaskar is head (equities), as the best performing fund during the March 2013 quarter. Five of the funds looked after by Bhaskar, including two that he manages directly, outperformed their categories by a wide margin.

UTI Opportunities Fund saw compound annual returns of 11.41 percent, beating the category performance of 4.49 percent over a period of three years UTI Equity Fund returned 10.38 percent and outperformed the category by a similar margin for the same period. Meanwhile, UTI Opportunities Fund also topped rankings released by Morningstar, another close tracker of mutual fund performance. PICK STOCKS MOVE ON

PICK STOCKS MOVE ON

Picking the right stock is, of course, important. And Bhaskar has had his fair share of right picks at the right time: ITC, Crisil, Sun Pharma and Tata Motors (when it was still the flavour of the season). But what makes Bhaskar different is that he does not make concentrated bets. When he sees his best picks performing, he starts lowering his exposure to them such that his portfolio is insulated from excess shocks.

“Anoop Bhaskar is a top-class fund manager with an eye for detail and goes through the grind to understand a company thoroughly. That’s what makes him a great stock picker,” says Soumendra Nath Lahiri, head of equity, L&T Mutual Fund.

Bhaskar himself says he follows a few simple mantras to pick the right stock: Buy companies with high returns on capital employed avoid promoters obsessed with size instead of performance buy companies where the promoters own at least half the stock and spot companies with strong cash flows.

But stock-picking is only half the story. The other half is that he does not push his luck too far by staying overexposed to a high-performing stock. This may mean short-term underperformance, since returns keep rising when a stock is on a winning streak. But fortunes change when a stock reverses to the mean.

This strategy ensures that over the medium- to long-term, many of the UTI funds have generated higher returns with lower risks. Jiju Vidyadharan, director, funds and fixed income, Crisil Research, reckons UTI’s outperformance is the result of investing in defensive sectors that have traditionally yielded lower risks.

Consider ITC: Around three years ago, the stock hit a purple patch and swelled to 7 percent of the UTI Opportunities Fund, which has a current size of Rs 3,610 crore. But the fund manager chose to divest a part of the holdings as the stock price increased. The stock has risen by 110 percent since January 2011, and had Bhaskar kept the original weight in the UTI Opportunities Fund, the stock would have accounted for around 9 percent of the portfolio.

But Bhaskar started selling the stock. The fund’s overall holding in ITC is now at 5.8 percent. Sebi allows funds to invest up to 10 percent in a single stock, but Bhaskar is not keen to push that limit. “I don’t want to run concentrated portfolios because you become a prisoner of it over a period of time,” he says.

FIRST MOVES

Forty-six-year-old Bhaskar’s stint with UTI began in 2007 when current Sebi chief UK Sinha was the chairman of UTI Mutual Fund. He had a reputation to live up to, as he had already built up a fan-following with his performance in the Sundaram Select Midcap Fund. (The fund returned 61 percent annually when the benchmark index had risen 44 percent over a four-year period from July 2003 to April 2007.)

His appetite for challenge was whetted at Sundaram in Chennai. But Bhaskar sought bigger opportunities by moving to Mumbai. The UTI job offer gave him that big break as he was handed three flagship schemes: UTI Equity, UTI Master Value and UTI Mid Cap, apart from being asked to oversee all the equity funds.

The first thing he noted was the funds’ heavy concentration in some sectors or companies. Not only that, the funds seemed to follow their own stock-picking rules with no benchmark to measure performance. They were often driven by the preferences of their fund managers, which meant that individual preference outweighed processes.

To the outside world, these funds were amorphous, and could not be categorised easily into large-cap, mid-cap or small-cap. Net result: Fund watchers would end up comparing UTI funds with all kinds of benchmarks, resulting in poor performance metrics.Bhaskar went back to the basics: For example, he benchmarked UTI’s Master Value Fund against peer groups and clearly defined the kind of asset allocation it needed in terms of large- and mid-cap exposures. He also defined the concentration limits in stocks and sectors with simple norms. He re-categorised the funds on the basis of their volatility and concentration in stocks and sectors, so that they could be compared with the right indices.

This helped UTI funds to make the right calls in order the beat the index. If, for example, it was felt that a sector’s weight was heavy in an index when the prospects were weak, UTI would have a lower concentration in this sector compared to the index, and vice-versa.

In December 2010, Bhaskar’s team decided to buy consumer stocks and reduce their weight in banks as they felt the sector was overvalued. The Opportunities Fund thus went overweight (22 percent) in FMCG when the index had only 12 percent of such stocks. On the other hand, against an index weight of 24 percent in banks, UTI reduced it to 12 percent based on relative sectoral outlook. These moves helped the funds deliver returns against the indices.

FROM THREAT TO OPPORTUNITY

But top-level turbulence lay ahead just when Bhaskar was getting into his stride. In February 2011, UK Sinha was nominated to head Sebi, and the government failed to appoint a new head at UTI as the finance ministry and UTI Mutual Fund’s main stakeholders (T Rowe Price, LIC and three public sector banks) could not agree on who should head the fund.

Omita Paul, the powerful advisor of then Finance Minister Pranab Mukherjee, was said to be pushing for the candidature of her brother Jitesh Khosla for the role of UTI chief. T Rowe Price, a global investment company which holds 26 percent in UTI, objected to this and the resultant stalemate ensured that UTI had no regular CEO for more than two years (the organisation is about to get one only now).

Staff morale plummeted as UTI operated like a headless chicken, and many officers sulked over low pay and top-level uncertainties. Harsha Upadhyay, a key fund manager who was managing the UTI Opportunities Fund then, resigned in June 2011 to join DSP BlackRock, a rival mutual fund.

Suddenly, UTI Opportunities also fell into Bhaskar’s lap in addition to the three funds he was already managing. Another one, the UTI Transportation and Logistics Fund, also went his way. But Bhaskar insulated himself from the uncertainties by focusing on picking the right stocks and sectors at a time when markets weren’t doing too well.

As the financial sector went downhill, his Crisil pick turned out to be a lifesaver. With a gain of 51 percent, it helped him outperform the category. His other bets on Tata Motors and Sun Pharma also paid off. Crisil was a stable non-cyclical stock Tata Motors was stable then and yet to be roiled by the domestic slowdown Sun Pharma was a good stock to own in a defensive sector.

Until September 2011, UTI Opportunities was a mid-sized fund with a corpus of Rs 750 crore. The UTI Wealth Builder Fund was merged with it to nearly double the size of the fund. Today, Opportunities is the biggest fund in the UTI stable, having doubled its size again. “He has this ability to adapt to various market conditions. Bhaskar can strike a balance between benchmarks and still follow his convictions at the same time, which is very rare,” says Vicky Mehta, senior research analyst at Morningstar India.

2003: THE TURNING POINT

Bhaskar’s life began revolving around stocks sometime in 1986 when he, along with his father, started buying shares through initial public offerings (IPOs). They got allotments in Hero Honda [now Hero MotoCorp], but failed to make money even after four years.

They hit the jackpot with HDFC in 1990 around the same time when Bhaskar was completing his MBA from Symbiosis in Pune. They held HDFC for nine years, and serious money led Bhaskar to take stock-picking seriously.

He got his first break with Brisk Financial Services in Delhi as a research analyst. He then moved to Siel Financial Services, then to Kothari Pioneer (India’s first private mutual fund) and to Franklin Templeton (which took over Kothari in 2002). His job largely involved doing research for stocks. But his heart was set on becoming a fund manager, and this break did not come until 2003.In 2003, he decided to move out of Chennai to a big broking house in Mumbai. But 15 days before the shift, he learnt about a vacancy in the Chennai-based Sundaram Mutual Fund. “I had this overwhelming desire to be a fund manager and to test whether one’s potential was the same as one thought,” Bhaskar says.

When Bhaskar met N Prasad, then chief investment officer (CIO) at Sundaram, he was presented with a stark proposal: Yes, he could become fund manager, but he would not be called one and, worse, he would have to take a 50 percent pay cut. He took the offer. The rest, as they say, is history.

He became the fund manager of Sundaram Select Midcap Fund which had a small corpus of about Rs 15 crore when Franklin Templeton’s Prima Fund had a size of Rs 1,700 crore. But fortunes were set to reverse in the boom markets of the mid-2000s by April 2007, the Select Midcap fund grew to Rs 2,500 crore while Prima Fund fell to Rs 1,500 crore.

“What makes Bhaskar interesting is the fact that he was a very successful midcap fund manager who actually moved on to manage large caps. That takes a totally different kind of learning but he has done it successfully,” says the CIO of a leading Indian mutual fund.

LUCK MATTERS

Bhaskar himself is more circumspect in claiming credit for his success, and says luck was in his favour. “I think what really worked for me was the fact that I was in the right place at the right time. I was plain lucky. Had I become a fund manager two years earlier, I would have been exhausted.”

The luck factor cannot be ignored. Anyone who picked stocks in 2003 would have looked like a genius in 2007, because the markets took off vertically. In 2003, the BSE Sensex was hovering around 3,250 points and good companies were available at rock-bottom prices. For example, Bhaskar bought 1 percent of Blue Dart at Rs 70 and sold the stock at an average price of Rs 1,600 over the next three years.

He also got into sugar stocks and construction companies like IVRCL he even went into real estate and was one of the very few fund managers to do so. He booked Rs 100 crore in profit in the sector. His fund made 10 times the money invested in Ansal Properties & Infrastructure and 100 times on Unitech shares. Bhaskar says he was fortunate to have got out of real estate before its shine went out. (He ran a portfolio with 20 percent cash which was still giving returns.) “From 2004 end, we started raising cash to 10 percent, and had 20 percent cash for a year to ensure that the fund didn’t fall faster compared to the peer group,” recalls Bhaskar.

So who did Bhaskar learn his tricks from? His answer: Siva Subramanian, his fund manager at Franklin Templeton who managed its Bluechip Fund and Prima Fund. “In this business, one of the biggest issues is to be able to retain a sense of proportion and balance, especially during good times. You have to have some humility about your performance. You have to maintain some equilibrium in your way of behaviour. I think Siva has shown me that,” he says.

First Published: Jun 18, 2013, 06:57

Subscribe Now