How Anita Dongre Tailored Her Business

Anita Dongre’s design and marketing strategy has targeted the urban, aspirational woman

For more than 12 years, Anita Dongre had been supplying Indian wear she had designed to high street shops in Mumbai, like the ones along Linking Road, one of the city’s shopping hubs. But when she decided to label her creations, she was bluntly rejected. “Kaun khareedega yeh, madam? Isme embroidery nahin hai! [Who will buy this, madam? There is no embroidery on it!],” was what she was told.

In the 1990s, although heavily embroidered Indian wear did good business at boutiques, they were not what young urban women were really wearing. Dongre had travelled abroad extensively, and had seen changing trends. Her friends, too, encouraged her to design clothes that they would be able to wear themselves.

“[The boutiques] didn’t have the vision I could see things changing around me,” says Dongre. She gives the example of a white linen shirt. “Every woman wanted that,” she says.

Hence, despite raking in money from selling the regular stuff, the rejection made her realise it was time to turn entrepreneur.

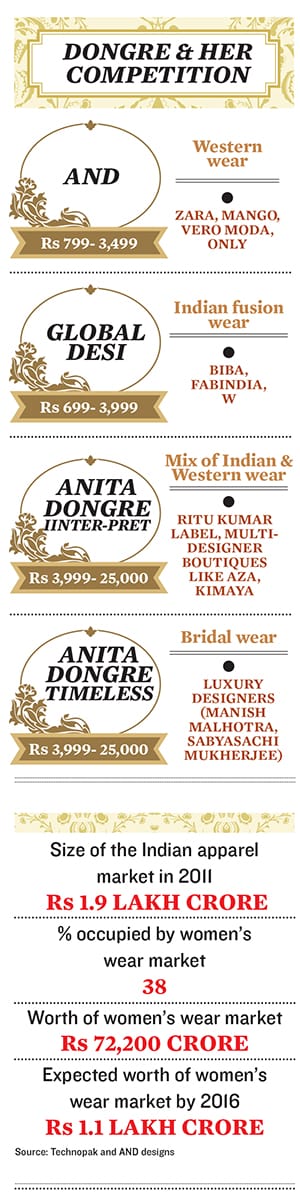

Not only did Dongre decide to persevere with her own line of clothes, she decided to retail them herself. Anita Dongre (AND) Designs was started in 1999, with a 300-sq-ft shop in Mumbai’s first mall, Crossroads. Thirteen years later, AND (the Western wear label), Global Desi (its ethnic counterpart), Anita Dongre iinter-pret and Anita Dongre Timeless now occupy 85 stores.

The four are slated to do a combined business of Rs 253 crore, with an EBITDA (earnings before interest, tax, depreciation and amortisation) of Rs 41 crore and a PAT (profit after tax) of Rs 30 crore in 2012-13. The growth in revenue is expected to be 128 percent from 2010-11, and growth in EBITDA of almost 183 percent. Dongre is headed to becoming the largest, most profitable and fastest growing Indian designer.

“The one key reason why designers in India haven’t been able to scale up is because they lack a CEO, or business head, who can manage their creativity and make it commercially viable,” says Arun Gupta, president, Future Ventures, which owns a 22.86 percent stake in AND Designs. There might be a lot of other designers who’re more creative than Dongre, but not everyone has the potent combination of creativity and the right commercial perspective.

Upstart Startup

The eldest of six siblings, Dongre hails from the hip Mumbai suburb of Bandra, minutes away from where one of her stores stands on Linking Road. She studied designing from SNDT, Juhu and Bcom from Narsee Monjee after which she worked as an in-house designer for export firms for two years.

Then she, and younger sister Meena Sehra, set up two sewing machines in the balcony of their house, and started supplying clothes to a boutique called Saks, which was frequented by Bollywood stars.

Dongre made a line of 12 linen dresses and showed it to Saks, who agreed to sell them. Over the weekend, nine of them were sold. On Monday, “I got a call saying they wanted more,” recalls Dongre. She was in business.

Coming from a traditional Sindhi family, Dongre initially faced resistance from her parents when she told them her plans. Her choice made them think she was being frivolous. But she didn’t budge.

Over the next 12 years, she became a successful supplier to almost all the famous boutiques in Mumbai. By this time, younger brother Mukesh Sawlani, who was working abroad as a banker, quit his job and joined his sister to manage the financial side of things. Sawlani is the CEO of AND, Dongre is the creative head, and Sehra manages production. In 1999, when they opened their first store, it was a decision they took collectively.

It is her family, again, that gave Dongre the ability to source her fabrics, one of AND’s main strengths. Her father was a manufacturer of children’s clothes, and guided her on who and where to source it from.

Finding the Sweet Spot

At the heart of AND’s success at scaling up is a model that takes a leaf out of famed retailer Zara’s book: Products positioned between designer wear that costs the moon, and mass market stuff that is cheap, but commonplace. This space is defined as the ‘bridge to luxury’.

Worldwide, at one end of the spectrum, there are marquee brands such as Louis Vuitton, Armani, Bulgari, Gucci and Burberry that are synonymous with luxury, and at the other end there are unbranded, cheap, mass-marketed clothes. In the middle is the bridge-to-luxury, which a customer crosses, before graduating to high-end luxury.

On this bridge stand global brands such as Tommy Hilfiger, Calvin Klein, Zara and Armani Exchange. These brands become relevant to upwardly mobile customers as they move up the value chain.

The Indian market is structured in much the same way. At the top end, there are high-end fashion designers vying with global brands, while at the bottom end there are thousands of players catering to the mass market. What makes the Indian market different is the dearth of brands in the bridge-to-luxury segment.Apart from foreign brands, which have a scattered presence in the major metros, there aren’t any brands that cater to the growing aspirational demands of upwardly mobile Indians.

Zara is the acclaimed leader in this space, and is doing business worth almost Rs 200 crore in India, just two years after opening its first store. It has just nine stores across four cities.

Dongre’s approach is unique, starting off in the bridge-to-luxury segment, and then moving up the value chain with Anita Dongre Timeless. Usually designers begin at the high-end luxury segment, and then move to commoditising their brand.

She is also heading towards the next big challenge: AND Men has just been launched. Very few designers are able to snag both genders.

The Backend

AND Designs has followed Zara’s strategy of showcasing fresh designs and multiple collections throughout the year. The company has eight or nine designers for AND and Global Desi, and they turn out new designs every month.

Every week, there are brand meets for each of the four brands, during which samples are displayed in front of Dongre and her merchandisers. They select the designs they like and check their commercially viability. Only then does a design go into production.

Nine merchandisers employed by AND study trends, purchasing power and willingness of customers to spend on certain clothes, and styles that work in Tier II cities as opposed to metros. They travel every month to various AND and Global Desi outlets in different cities to gather customer data.

They speak to the staff at these stores about what customers like, and what they are looking for. For instance, a girl in Lucknow will be willing to spend Rs 2,000 on a pair of jeans, but Rs 1,000 for a top. The merchandisers also found out that coloured denims, currently in vogue, had skipped the design teams’ notice, and were not available in any of the AND stores. The data provides an insight into what designs will work and what will not, and helps in taking decisions on the quantity of each design that should be stocked.

One of the key factors behind Zara’s success is its excellent logistical network, which allows it to refresh designs at its 1,600 stores globally almost simultaneously. For Dongre’s company, churning out fresh designs every month to more than 85 stores and more than 270 points of sale is quite a challenge. Although its logistics and distribution is running smoothly at present, it might pose problems as AND scales up.

Dongre has also avoided using the Bollywood route to building her brand, unlike luxury designers Sabyasachi Mukherjee and Manish Malhotra. Eight or nine years ago, Dongre had been the designer for a film. Her experience had been a harrowing one, and she vowed never to work for a movie again. “Bollywood needs stylists, not designers,” she says. “A lot of these stylists pick up clothes from my stores, but just as regular customers.”

But opinion is divided on how useful the Hindi film industry is. “In a country obsessed with religion, cricket and Bollywood, it would be silly not to partner with Bollywood to take your business forward. Bollywood can be very difficult or very embracing, depending on your personality. It is very difficult to make inroads,” says Mukherjee.

Malhotra has a different take on the issue: “Bollywood definitely helps you get noticed, but it doesn’t guarantee fame. You will sell a few garments, but what after that?”

First Published: Nov 05, 2012, 06:26

Subscribe Now