When Narendra Bansal, the 53-year-old chairman and managing director of Intex Technologies (India) Ltd says, “I don’t understand technology”, it is a candid statement from the head of one of India’s largest home-grown manufacturers of consumer durables and computer accessories. But then, Bansal has always been a straight arrow throughout his entrepreneurial journey, which began even as he was studying commerce at Delhi University’s Swami Shraddhanand College in 1986.

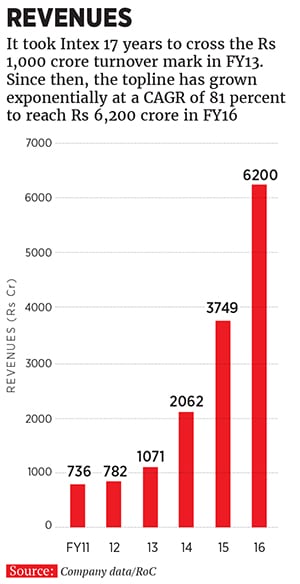

Bansal has hired professionals who “understand technology”. His own lack of technological knowhow has been more than offset by his nose for business and, in his own words, “an ability to identify a product, a buyer and a supplier for it”. This has helped him grow Intex into a Rs 6,200-crore diversified company with a product portfolio that includes feature phones, smartphones, LED TVs, multimedia speakers, washing machines and refrigerators.

No mean feat, for a firm that began in 1996 as a little-known supplier of imported ethernet cards (a computer peripheral that enables wired or wireless data transmission over a network) in the IT markets of Delhi. Consider some other facts: Currently, the Delhi-based Intex has a pan-India presence through 1.5 lakh retail outlets, 1,800 distributors and 1,500 service touch points. Intex even exports its products in small quantities to Nepal and Latin America. It has four manufacturing plants, two each in Jammu, and Baddi in Himachal Pradesh. A fifth facility, which Bansal promises will be one of the largest of its kind in India, is coming up near Noida in the National Capital Region.

Intex has three offices in Delhi’s Okhla Industrial Area, which has, over the years, become congested with trucks loading and unloading material in warehouses. To better showcase the size and stature that Intex has gained in recent times, the company is building its swanky glass-and-steel headquarter in Gurugram, near Delhi, which, Bansal says, will be ready in the next couple of years.

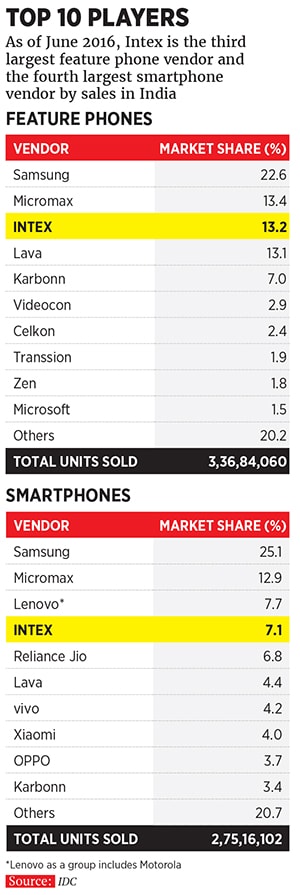

As of June 30, 2016, Intex is the third largest feature phone brand in India, behind Samsung and Micromax, with a 13.17 percent market share, according to market intelligence firm IDC. In the smartphones segment, it is the fourth largest brand with a 7.1 percent market share, behind Samsung, Micromax and Lenovo. In the April-June period, Intex sold 19.52 lakh smartphones and 44.34 lakh feature phones in India.

Consumer durables, including mobile phones, are a low-margin, high-volume business and, according to Bansal, Intex operates at a healthy operating profit margin of 4 percent. According to data from the Ministry of Corporate Affairs, Intex clocked profit after tax of Rs 152.8 crore in FY16, a growth of 20 percent from the Rs 127 crore in FY15. Its revenues in FY16 grew 70 percent to Rs 6,212 crore from Rs 3,651 crore in the previous fiscal.

The spurt in handset sales and revenues can be attributed to Intex’s branding and marketing activities over the last three years, led mostly by Bansal’s 24-year-old son Keshav. The company has roped in brand ambassadors like Bollywood actors Farhan Akhtar, Madhuri Dixit, Telugu actor Mahesh Babu, Kannada actor Sudeep and Tamil actor Suriya. Last December, they made a successful bid for Gujarat Lions, the Rajkot-based cricket franchise in the Indian Premier League (IPL).

What makes Bansal’s entrepreneurial journey further intriguing is that Intex is a bootstrapped company completely owned by the Bansal family, it has never raised external equity and is free of net debt. (Its relationship with lenders is mostly limited to non fund-based credit lines needed for external trade as Intex continues to import, mostly from China, a significant portion of the equipment used in its smartphones, speakers and television panels.)

To understand how Bansal pulled this off, it is essential to trace his entrepreneurial journey to the time before he established Intex in 1996.

After his graduation, Bansal was loathe to joining his father’s grain trading business based out of Naya Bazar in Delhi’s Chandni Chowk area. “It was a typical Indian wholesale market with traditional merchants and porters carrying sacks of grains on their backs,” says Bansal. “That environment didn’t appeal to me and I knew this was not what I wanted to do.”

But Bansal didn’t want to borrow money from his father either and had to come up with a business idea that wouldn’t require much seed capital. After doing a recce of several markets in Delhi, including Nehru Place, Palika Bazar and South Extension, Bansal decided the ideal business for him would be to deliver some kind of service. Those were the days when cordless phones had become a rage in India. So Bansal decided to start a venture offering repair services for cordless phones in Delhi. He posted a classified ad in a local newspaper that promised customers home pick-up and delivery of their phones and hired a technician to repair them. “This was 25 years ago when there was no concept of doorstep service, but I identified the demand for it and started my business,” says Bansal.

To bolster his income, Bansal procured a Polaroid camera to take photos of tourists outside the Birla temple in Delhi, and got them printed on key chains to be sold as souvenirs. Then came the idea of trading in audio cassettes. Bansal would procure small batches of cassettes (whatever he could manage to get on credit since he couldn’t pay for them upfront) from suppliers and sell them to shopkeepers around Delhi.

![mg_88753_intex_revenue_280x210.jpg mg_88753_intex_revenue_280x210.jpg]()

While these businesses sustained Bansal in the short term, he knew they weren’t for posterity, and he had to come up with a more sustainable business plan. The first time Bansal made some serious money was when he imported sealed maintenance-free (SMF) batteries (used in inverters and power back-up devices) from Taiwan, which were in great demand in India but not easily available. “This was in 1992-93 and I was earning Rs 1 lakh a month in those days from this business,” recalls Bansal.

In the same year, Bansal, who got most of his business ideas by wandering through the markets of Delhi and identifying products that were in demand but in short supply, started selling imported floppy disks and drives. “There were only one or two multinational brands that were available in India for such products at the time. Very often, these disks and drives were sold in the grey market at exorbitant prices, without any bill, warranty or after-sales service,” Bansal recounts. “I decided to import these products and sell them under my own brand at one-tenth the price [of the grey market], and follow it up with warranty and after-sales service.”

Bansal points out that one of the reasons he was able to carry out business activities without much capital in the initial phase was his ability to procure products, first from India and then abroad, on credit and then repatriate the dues of suppliers after retaining his share. To convince suppliers to do business with him, he’d very often visit them in their home countries including Taiwan and Singapore, at his own expense. “Everyone wants to do business and if you are honest and transparent in your dealings, they will relent,” Bansal says.

But while he managed to procure products on credit, he also made it a point to sell them to shopkeepers only in exchange for demand drafts or post-dated cheques to maintain control over receivables and only against a legitimate bill. As the IT peripherals segment was dominated by grey market players, Bansal faced a lot of resistance from shopkeepers due to his terms and conditions. “But my products were of good quality and I followed it up with diligent after-sales service, which led to a demand for them,” explains Bansal.

As his business grew, Bansal founded Intex in 1996 with a seed capital of Rs 20,000 from his personal savings. History kept repeating itself as he began importing ethernet cards, computer cabinets, multimedia speakers and selling them in India under the Intex brand each time challenging the monopoly of the few brands that existed in each segment with good quality products at low prices and regular after-sales service. The company’s product range kept expanding to include cathode-ray tube TVs, then LCD and LED television panels and eventually mobile phones. All along, Intex remained debt-free.

Giving the raison d’être for Intex’s ability to grow without external funding, Ramesh Vaswani, Intex’s 74-year-old non-executive director and former vice chairman, says that Bansal and he ran a tight ship at Intex. “With the help of strong internal control systems, we didn’t allow any leakages in revenues. Also, the promoter didn’t take any money out of the company. The profits and surplus generated were ploughed back into the business,” says Vaswani, who joined Intex in 2002. “We also developed a strong relationship with vendors and got credit from them, as opposed to giving them cash advance. We don’t show sales in our books without supporting monetary collections. If a buyer fails to give us post-dated cheques within a specified due date, we stop supplying to him.”

Ask him about people who have been a positive influence on him in his entrepreneurial journey and the first name that comes to Bansal’s mind is Vaswani’s. He helped Bansal professionalise Intex by implementing an exhaustive enterprise resource planning system.

While Bansal, with the help of people like Vaswani, laid the foundation for Intex’s growth over the last two decades, it translated into an exponential growth in revenues only in the last three years. It took Intex 17 years to cross the Rs 1,000 crore turnover mark, in FY13. But since then, the company’s topline has grown at a compounded annual growth rate (CAGR) of 81.47 percent to reach Rs 6,200 crore in FY16.

Intex started selling multimedia speakers in 2000 and feature phones in 2007. The company has always assembled its cell phones from imported components at its Indian facilities, the first of which was set up in Jammu in 2001. But the spike in topline growth came after it began selling smartphones and LED TVs in 2012, and washing machines in 2013.

![mg_88755_top_player_280x210.jpg mg_88755_top_player_280x210.jpg]()

Currently, sale of cell phones contributes around 85 percent of Intex’s revenues, and in a market teeming with local players like Lava, Karbonn and Micromax and international players like Samsung, Lenovo, Xiaomi and Oppo, Intex has managed to stay afloat. Its overall market share (feature phones and smartphones) grew from 4 percent in the last quarter of 2013 to 12 percent in January-March 2016, according to IDC data.

Tarun Pathak, a senior analyst with Counterpoint Technology Market Research, says, “being in the right place at the right time” helped Intex grow its market share. While Intex has traditionally been strong in the feature phones segment, which still accounts for half of all mobile handset sales in India, its smartphone offerings in the smaller towns and cities, where people were looking to upgrade from a feature phone to their first smartphone, helped, he adds.

Intex competed well on pricing and distribution, especially in the entry-level 3G smartphone market. Its extensive distribution reach was a result of the relationships it had fostered with distributors and retailers of its other products. According to Keshav, who is director at Intex, the brand still enjoys a market leadership position in the sub-Rs 5,000 smartphone segment.

While mobile phones are the mainstay of Intex’s earnings, it has plans of ramping up its consumer durables business as well. “Right now, consumer durables comprise 15 percent of the company’s revenues. We want to ramp up this share to 25 percent by FY17,” says Keshav.

Intex sells around 2 lakh multimedia speakers, 1 lakh power banks and 50,000 LED TVs every month. It is expanding its portfolio to include ultra-high definition and smart LED TVs, fully-automatic washing machines and air purifiers, and wants to start selling air conditioners, according to Nidhi Markanday, head of consumer durables and IT at Intex.

According to Keshav, who joined the business in 2012 after graduating from the Alliance Manchester Business School in the UK, the only ingredient that was missing in Intex’s recipe for success was brand perception, which had to be driven through aggressive marketing and brand promotion.

Starting in 2013, Keshav suggested ways for the company to connect with customers and the efforts appear to have paid off. Roping in actors as brand ambassadors was a step in that direction. But the biggest and boldest move came last December when Intex bought IPL team Gujarat Lions. “I did the math and presented the proposal to the management and it took them just 20 minutes to agree,” says Keshav. The decision entailed an upfront investment of at least Rs 80 crore (though some of it is recoverable from jersey sponsorships and ticketing revenues), but Intex isn’t treating Gujarat Lions as a potential profit centre. Keshav and Intex are conscious that they have this IPL team for a two-year period, during which they have to make Intex a household name. The team’s good performance in the tournament—finishing the league stage at the top of the table before losing out in the qualifiers for the finals—helped matters.

Using an association with cricket to connect with customers isn’t a new strategy for mobile handset makers. Chinese brand Vivo is the current title sponsor for IPL, Micromax is the title sponsor for some cricket tournaments featuring the Indian team, and others like Lava, Karbonn and Oppo too have had their fair share of association with cricket. But Intex has decided to go the whole nine yards. Not only does it get brand mileage as the owner of an IPL team, it is also an on-ground and on-air advertiser at the annual event.

The senior Bansal approves of Keshav’s IPL strategy. “It is a masterstroke that has helped sales. The national visibility and credibility of the brand has grown manifold with all stakeholders,” he says.

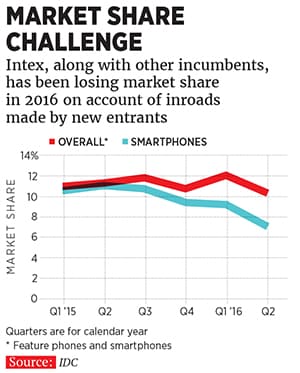

But rapid growth and intense competition has brought in its own set of challenges for Intex. Its market share in the smartphone business in April-June 2016, according to IDC, has dipped to 7.1 percent from 9.2 percent in the preceding quarter.

The loss for Intex, as indeed for some of the other top incumbents like Micromax and Samsung, has been on account of inroads made by new entrants like Reliance Jio (owned by Reliance Industries Ltd, which also owns Network 18, the publisher of Forbes India), Oppo, Vivo and Xiaomi.

Kiranjeet Kaur, research manager at IDC’s Asia Pacific Client Devices Group, says that while Chinese brands are selling smartphones that are a little more expensive than those sold by the likes of Intex, they are aggressively pushing their products through the retail sales channels by offering distributors and retailers higher commissions.

There are other systemic issues as well. Though shipments of smartphones in India grew in April-June 2016, it had declined year-on-year in the previous two quarters. The recent sluggishness in the Indian smartphone market has been most severe for entry-level phones. “Demand has slowed down in the entry-level market in tier II and tier III towns, due to lack of awareness about the full potential of these devices, lack of adequate vernacular content and poor battery life of these smartphones compared to feature phones,” according to Pathak. This affects companies like Intex since a large chunk of its smartphone sales are in this segment.

According to recent news reports, management attrition is also a challenge that Intex is facing. Intex’s Chief Financial Officer Rajeev Jain, however, says that in the next phase of its growth, the company is transforming into a “more professional organisation”, with a decentralised strategy of clearly defined roles and responsibilities of functional heads. The company says it has hired new talent from companies including OBI Mobile, Bharti Airtel, Microsoft, Godfrey Phillips India, Tech Mahindra and ZTE Mobile in senior management positions. “Our attrition rate is among the lowest in the industry. We have very strong HR policies that attract and reward the best talent,” says Jain. “The transformation process is going on as per strategy. We are at present a family of over 11,000 direct and indirect resources.” Both Pathak and Kaur concur that in order to regain market share, Intex will need to differentiate itself by focusing on building an ecosystem around its devices. “Intex may consider expanding its range of 4G-enabled devices, where its portfolio is limited compared to some of the Chinese brands,” Pathak suggests.

![mg_88757_intex_market_share_280x210.jpg mg_88757_intex_market_share_280x210.jpg]()

Plans are also afoot to build an ecosystem that would make its devices more attractive to customers. The company has launched devices such as smart wearables and even a Google certified Virtual Reality Cardboard at extremely competitive prices there are more such products on the anvil.

Intex has spent around Rs 400 crore on R&D over the last seven years, and plans to increase this to Rs 1,000 crore over the next three years. The company also plans to increase the share of revenue from value-added services by controlling the software on the devices it sells. “The mobile handsets business has been commoditised to a certain level. A brand like ours has to innovate and evolve in order to maintain our position in the minds of consumers,” says Keshav.

Consequently, after launching the Cloud FX smartphone powered by an operating system (OS) designed by the open source foundation Mozilla three years ago, it is now coming up with another smartphone that will run an OS designed by US-based Cyanogen Inc, which develops open-source OSes based on Google’s Android. Intex is also developing its own OS called IDMOS (Intex Designed Mobile Operating System), which will be its own modification of Android.

The father and son have different ways of articulating Intex’s vision. Keshav wants to see Intex become a $6 billion (by revenue) enterprise over the next four to five years. The worldly-wise Bansal’s dream is to see Intex evolve into a world-class and professionally-run institution, globally synonymous with the chutzpah of Indian entrepreneurship.

For this, it is essential to take Intex public, Bansal feels. “Intex doesn’t need funds for growth and if an initial public offering (IPO) happens, it will just be an offloading of a portion of the promoters’ stake to unlock the value created over the years,” he says. Though Intex is yet to set a date for its IPO, it has appointed Edelweiss and Axis Capital to take it public. “External equity means more responsibility, scrutiny and brand visibility. Getting professionals and external experts on the board will add value to the company,” Bansal says.

Unlike many traditional Indian businessmen, Bansal says he does not believe in idol worship, but he is firm on his quest to create an icon out of Intex. And today he is far closer to that dream than ever before.