Budget 2019: For social schemes, no new solutions to the same problems

While Sitharaman addressed the water crisis, no major changes were made to flagship schemes such as the Swacch Bharat Mission and the Awas Yojana

Vishal Bhatnagar for Forbes India

One of the major focus points of Nirmala Sitharaman’s Budget 2019 speech was ‘transforming rural lives’. While the Finance Minister outlined the achievements of social schemes such as the Swachh Bharat Mission, Ujjwala Yojana, Saubhagya Yojana and Pradhan Mantri Awas Yojana, there haven’t been any major changes in these existing schemes.However, considering the seriousness of the water crisis, Sitharaman spoke about managing water resources and supply. “The government will work with states to ensure Har Ghar Jal (piped water supply) to all rural households by 2024 under the Jal Jeevan Mission,” she said. Apart from using funds under the existing schemes, the government might use additional funds under the Compensatory Afforestation Fund Management and Planning Authority (CAMPA).

Since 2014, through the Swachh Bharat Mission (SBM), about 9.6 crore toilets have been constructed and more than 95 percent of cities and 5.6 lakh villages have been declared open-defecation free. Going forward, “We must not only sustain the behavioural change seen in people but also harness the latest technologies available to transform waste into energy,” Sitharaman said.

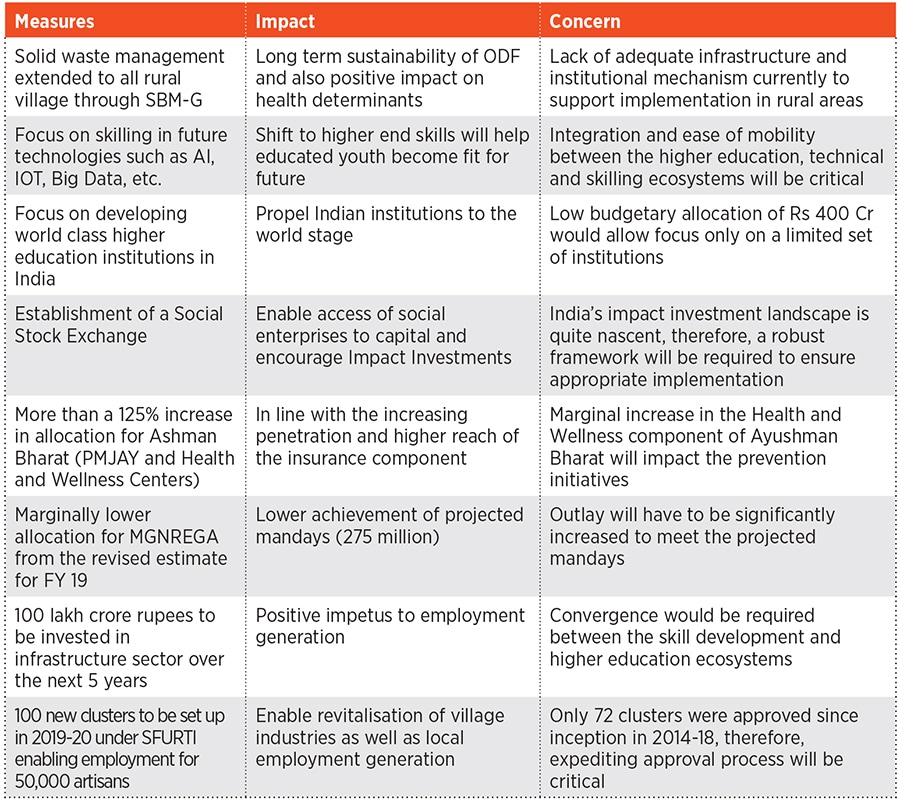

Sitharaman emphasised that the next phase will be to undertake sustainable solid waste management in every village. “The government already has schemes and targets in place for drinking water and solid liquid waste management. But the biggest concern remains: Where is the money going to come from?” says Yamini Aiyar, president and chief executive, Centre for Policy Research.  Analysis by PwC

Analysis by PwC

Apart from SBM, Sitharaman said the Ujjwala Yojana and Saubhagya Yojana have seen significant impact, with the provision of 7 crore LPG gas connections and close to 100 percent households getting electricity. Sitharaman added that by 2022, every single rural family, except those who are ‘unwilling to take the connection’ will have electricity and clean cooking facilities.

However, according to Aiyer, these moves aren’t bold enough. “Not much changed from what was announced during the Interim Budget,” says Aiyar.

Launched in 2015, the Pradhan Mantri Awas Yojana’s target this budget is to reach 1.95 crore houses (rural India), in this second phase, by 2022. A major issue with this scheme, as reported by Forbes India in June 2019, was targeting the right people and a delay in receiving payments. The Budget has made no revisions for these administrative issues.

“There is a lot of clutter in the way we have implemented social welfare policies. We have over 400-500 schemes… these need to be rationalised so that they address core issues,” adds Aiyar.

Under the Pradhan Mantri Jan Dhan Yojana, launched in 2014, 33 crore bank accounts were opened across India. However, according to Manoj K Sharma, Director, MSC (MicroSave Consulting), 65 percent of women either still lack a bank account or have accounts that have turned dormant. Sharma says, “There is a need to move from Jan Dhan to Jan Samriddhi and create financial products that the poor, especially women, find useful. This could include long-term structured saving products that enable livelihood opportunities in goat farming, piggery, among other areas.”

First Published: Jul 05, 2019, 17:54

Subscribe Now