The Indian summer of Western fashion

To trace India's contribution to Western fashions, stop by at two exhibitions at London's V&A Museum this autumn

It might be subtle as a pattern of stitching or eye-catching as a burst of glitter. It might be a vivid combination of blue and green that suggests peacock feathers or the foliage of a pleasure garden. But when it comes to the most sought-after clothing and jewellery produced by designers in Paris, New York or Milan, there is nearly always an Indian element.

Fashion editors in Europe and the US regularly anoint styles like tunic tops, tie-dyed scarves or embroidered jackets as the latest high street trend, often under the moniker of “hippie chic” or “luxury bohemian”. Yet the Indian aesthetic has never really gone out of style. As shown by a pair of exhibitions, on this autumn at the V&A Museum in London, Indian ornamentation and design skills have been a major influence on European tastemakers since at least the 19th century.

Weaving Indian design into the fabric of trade

The watershed event in that history was the Great Exhibition of 1851 in London. The Indian works on display in the famous Crystal Palace that year, which included Gujarati silk brocades, Kashmiri shawls and fine muslins from Bengal, were framed as paragons of design and skill for Western audiences. It was a time when rapid industrialisation in Britain and Europe was eroding traditional crafts as well as aesthetics. “Discussions were being held at the arts schools on how to bring elements such as proportion of motif to background and harmony to colour back into mass manufacture so you wouldn’t have soulless products,” says Divia Patel, co-curator of The Fabric of India, one of the two fall shows at the V&A. “Indian textiles in particular were held up as examples of what good design should be.”

Some of this had to do with instilling a more refined aesthetic sensibility into products meant for the domestic British market. But it was also about developing India as an export market throughout the second half of the 19th century, with British manufacturers copying designs that would appeal to Indian buyers. This strategy would have wide-ranging consequences. On one hand, it undermined the Indian textile economy as local craftspeople could not compete with cheaper, industrially made products. On the other, it started a process of aesthetic cross-pollination of Eastern and Western ideas that continues to the present day.

“So much of what we think of as quintessentially Indian now, like the paisley motif, has been through the mill of Western influence and come out on the other side,” says Rosemary Crill, co-curator of The Fabric of India. “It started out as an Indian motif, then it was slightly tweaked for the European market, and then exported back to India.” The same is true of certain floral patterns that originated as Mughal designs but were re-interpreted for Western markets before returning to India in a mass-market form.

Today, as places at the global trading table have shifted yet again, it’s even harder to say where one cultural imprint starts and another ends. But there are a few areas where the Indian influence is readily discernible in contemporary global fashion. From mall store chains catering to teenagers to top-end designers creating gowns for film stars, they all come to India for embellishments like embroidery, stitching and beading. The only difference is the extent to which fashion manufacturers acknowledge that influence, since the ‘Made in…’ label on clothing does not state all the countries where an item was worked on, but only the one where it is finished.

Some Western designers, such as Belgian couturier Dries van Noten, are proud of their Indian associations. “He’s had an embroidery workshop in Kolkata since 1987, and he’s been very vocal about his engagement with those craftsmen,” says Divia Patel. Other high-end fashion designers who have given prominent place to Indian embellishment include Christian Dior and Alexander McQueen along with Karl Lagerfeld, Giorgio Armani and Jean Paul Gaultier.

As an example of the opulence that has inspired many a European luxury collection, the famous costume worn by Madhuri Dixit in publicity images for the 2002 film Devdas will be one of the highlight pieces on display in The Fabric of India at the V&A. (This is the original, 30-kilogramme version of the dress, requiring a specially designed mannequin to bear its weight.) Its combination of zardozi embroidery with Gujarati mirror-work represents the decorative impulse taken to its logical extreme: To the point where clothing becomes jewellery, or vice versa.

Adding new words to the language of adornment

Bejewelled Treasures, the second autumn show at the V&A, reveals the direct link between Indian traditions of ornament and the evolution of European jewellery design in the early 20th century. Paris’s creative industries drove the trend. Jeweller Jacques Cartier went to India for the first time in 1911, bringing back a wealth of impressions as well as contacts in the gem trade. As a result, there was a huge increase in both the number and type of precious stones imported from India to France in the following decades. Carved Indian jewels had a particular impact.

Fashion designer Paul Iribe chose one of these gems, a large carved emerald, to be the centrepiece of a brooch that became a prototype for the Art Deco style. “He used all the colours of Mughal and Iranian book painting and drew on elements of Chinese art as well to create a hybrid Oriental aesthetic that became the taste of the age,” says Susan Stronge, curator of Bejewelled Treasures. “Paul Iribe was the first person to do that.”

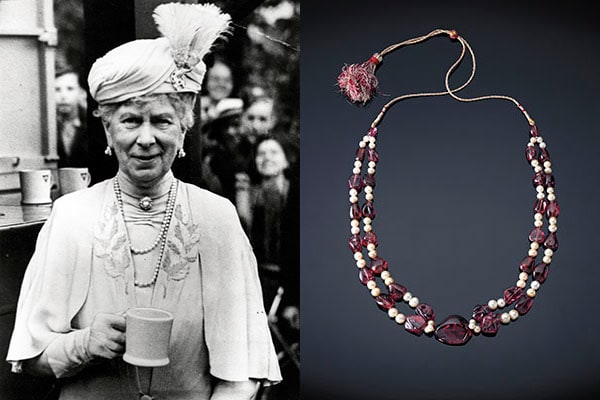

One of Iribe’s collaborators, fashion designer Paul Poiret, also took inspiration from India. Poiret is credited with ushering in the craze for turbans that swept Europe and America in the 1920s. Worn by women as well as men, these ready-to-wear turbans were often decorated with the same kind of feathered or jewelled ornaments seen on the heads of the Indian princes who were the era’s most fashionable party guests. Meanwhile, the long pearl necklaces favoured by maharajas migrated to the necks of flapper girls, thereby becoming one of the decade’s signature accessories. Image: Reuters

Image: Reuters

The Autumn-Winter 2002-03 collection of Belgian designer Dries van Noten used Indian motifs and techniques

Similar to the cross-fertilisation that occurred between Eastern and Western design in clothing, fashions in jewellery also quickly became hybridised. Led by the Maharaja of Patiala, Indian royal families began having their family jewels re-set in Europe in the 1920s and 1930s. This not only meant incorporating elements of Art Deco style, but also using platinum instead of gold. Jewellers both past and present have taken advantage of platinum’s relative lightness to afford a greater range of expression.

Some of the pieces in Bejewelled Treasures, which are all drawn from the collection of Sheikh Hamad bin Abdallah al Thani, include examples of contemporary Indian design that hearken back to the glamour of the Jazz Age, such as a ruby and diamond pendant brooch by the star jeweller of Mumbai, Viren Bhagat. But apart from showing off the jewels themselves, the emphasis of the show is on the skills behind them.

“Whether made in India or in the West with an Indian influence, what we hope to convey is the extraordinary level of craftsmanship involved,” says Susan Stronge, the exhibit’s curator. More specifically, she says that skills like kundan and enamelling should be better known in the West, as “they are among the glories of Indian art”. Image: Keystone / Getty Images

Image: Keystone / Getty Images

Jewelled turbans worn by Indian kings inspired fashion trends in the West a spinel and pearl necklace from the Mughal era

Celebrating the Indian influence

Those particular skills, along with the centuries-strong tradition of Indian handicraft in general, constitute a common thread between Bejewelled Treasures and The Fabric of India. The two shows are part of the V&A’s 2015 India Festival, which includes everything from live concerts and storytelling events to a digital exhibition of Indian musical instruments, along with a Diwali-themed cultural festival for children.

Apart from being a celebration of desi culture in Britain, the purpose of the India Festival is also educational. “People often have quite a romantic view of India, especially those who have never been there,” says Anna Jackson, keeper of the V&A’s Asia department. “We’re trying to provide a bigger perspective historically, to give people an idea of how dynamic a place India is, and how important it was and is to the world economy.”

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

The Fabric of India opens on October 3, and runs through January 10, 2016 at the V&A. The first major exhibition of handmade Indian textiles, it will include about 200 objects ranging from some of the earliest known surviving fragments of Indian fabric up to the latest creations by India’s present day fashion designers. Bejewelled Treasures opens on November 21 and goes until March 28, 2016. It comprises about 100 objects that are either sourced directly from or inspired by the jewellery traditions of India, and includes a number of Mughal items along with a gold finial and a jewelled bird from Tipu Sultan’s throne.

First Published: Oct 20, 2015, 07:43

Subscribe Now(This story appears in the Aug 13, 2010 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, Click here.)