Sanjna Kapoor: To the theatre born

Films may define her family name but Sanjna Kapoor has found her métier as a cultural entrepreneur

Sanjna Kapoor laughs easily. It’s the kind of clear, delightful laughter that stays with you long after you’ve left the room. It’s also what I first notice as we step into the home-office on the third floor of her house in New Delhi’s diplomatic enclave in Chanakyapuri. “Three hours!” she says as she takes her seat behind a table. “What do you want to talk about for three hours?” I sputter something incoherent in response. She laughs. “I mean, I’m interesting. But I’m not three-hours interesting.”

She’s being modest.

For 21 years, she enlivened Prithvi Theatre in Mumbai’s Juhu suburb, drawing in audiences despite the constant competition from pop-cinema. Then, four years ago, she moved out of her comfort zone to start a new venture, Junoon, a platform which enables engagement with the arts.

This Kapoor is, simply put, a theatre evangelist. And the reason for that isn’t far to seek. Her family name may be synonymous with Indian films, but for Sanjna, while growing up, “theatre was all-consuming”. After all, her parents, Shashi Kapoor and Jennifer Kendal, were both stage actors first. As were their respective forebears, the legendary Prithviraj Kapoor and Geoffrey Kendal, an English actor-manager who lived in and toured across India for many years with his travelling theatre company Shakespeareana, along with wife Laura Lidell and two daughters. “When I got to know what it was that I was fired about, it still felt very personal,” says Sanjna. “It was my joy, my thrill, my love. Of course it touched other people, but I didn’t quite know how to express it.”

But her personal engagement to theatre wasn’t just a result of her family’s thespian talents. It was also manifest in a physical structure.

Sanjna was about 10 when the Prithvi Theatre that her parents were building was complete. This was in 1978. “[Before that], during breakfast, my mother and the architect would pore over the blueprints,” she recalls. She would discuss the details of the building and how they wanted to build it. “I love blueprints ever since.” Her parents’ brainchild was both a tribute to the legacy of Prithviraj Kapoor and his travelling company, Prithvi Theatres, as well as a home for the kind of theatre that they loved. “I remember going to Prithvi and loving it because I could go to the back row, lie down and sleep,” she says. The shows would start around 9 pm, which was past her bedtime. So she would watch the beginning of the play, and nod off. “I’ve always loved sleeping with those sounds, people murmuring and conversations they gave me great comfort.”

Her informal education in the arts continued beyond the walls of Prithvi too. When she was only 12, Sanjna toured Ireland with her maternal grandparents, playing Olivia in Twelfth Night and Titania in A Midsummer Night’s Dream. Although she travelled with them later across India too, this was special, she says. She got a glimpse into their world, and “it was beautiful”.

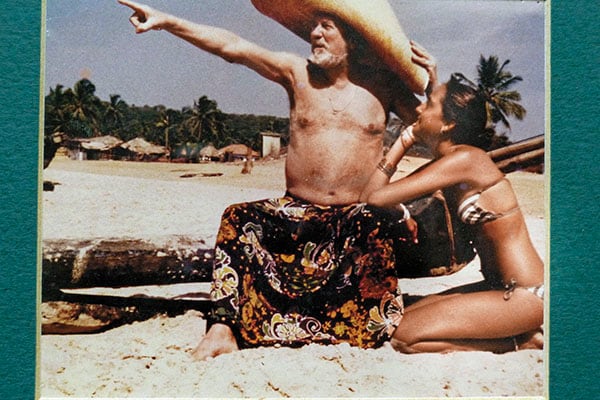

Photo courtesy: Sanjna Kapoor

Sanjna with grandfather Geoffrey Kendal

This world that she speaks of was recreated in the 1965 Merchant and Ivory film, Shakespeare Wallah, in which a British travelling theatre troupe journeys through India. Largely based on the experiences of Shakespearana, the film had Geoffrey Kendal and his wife essaying characters modelled on themselves. In it, the male lead, Sanju, played by Shashi Kapoor, falls in love with Lizzie Buckingham, played by Geoffrey’s younger daughter, Felicity. “The movie was so close, and yet so not close to their [her grandparents’] story,” says Sanjna. The depiction of their travels, adventures and tribulations may not have been completely accurate, but the film offered something rare: An opportunity to capture the ephemeral world of theatre. “That’s why it is so important to recount stories,” she says.

And the 48-year-old Sanjna, who was brought up on stories of Shakespearana and Prithvi Theatres’s travels, now has some of her own.

Even as a young girl, Sanjna knew that she wanted to become an actor. Also that she had to do it one of two ways: “Either I had to learn on the job as most people in my family did. Or I had to go to school.” She chose the latter, and applied to acting schools in England after her class X exams. Her early attempts were unsuccessful but she managed to land a role in Ketan Mehta’s 1988 film Hero Hiralal opposite Naseeruddin Shah. “I clearly understood there that I didn’t have the tools and the wherewithal to act in a film,” she says. “And I would see Naseer and he always knew what to do.” So she applied to, and was accepted at New York’s Herbert Berghof Studio (HB Studio).

“It was lovely in New York,” she says. Nobody knew of her storied family heritage, or who her father was. “This was my rebellious phase. I was seeking anonymity knowing that it wasn’t possible in India.” Herbert Berghof, a prolific actor and one of America’s greatest acting teachers, was by then in his late 70s. He had built the studio with his wife, German actress Uta Hagen. Sanjna went there in 1986. When she opened the door to the studio, “the most extraordinary thing happened! The first thing I smelt, it wasn’t as much a smell as it was a sensation I sensed Prithvi of the 1983 Prithvi Theatre Festival.” She speaks about this often, attributing this “sensation” to the fact that the studio was created by actors who loved their craft and needed to share it.

“I would love to build something like that,” she says of the simple brick structure within which the studio was housed. “For me, building something was always very important.”

As she speaks, it’s hard not to notice an enlarged portrait of a man’s face on a dark background that hangs on the wall just behind her desk. It’s of her father, Shashi Kapoor, whose career as an actor in Hindi films is the stuff of legends. But his wasn’t a path she would follow, and her time in New York made her realise that. “It was very clear that I didn’t want to be a part of the masala film industry,” she says. “I would watch my dad’s films in the 80s and they were so violent!” Her eyes widen as she talks about the anguish she felt while watching some of his later films. “I’m not a great feminist but my woman-ness would be bruised by the appalling things men were doing to the women in the films.” She recalls asking her mother: “How can he do this?” And Jennifer would explain to her how different the film industry had been when he had started out. The experience was collaborative and an actor was a part of everything, from the script setting to the lyrics. Things changed. And by then, there were bills to be paid, and a family to support, she says. Image courtesy: Sanjna Kapoor

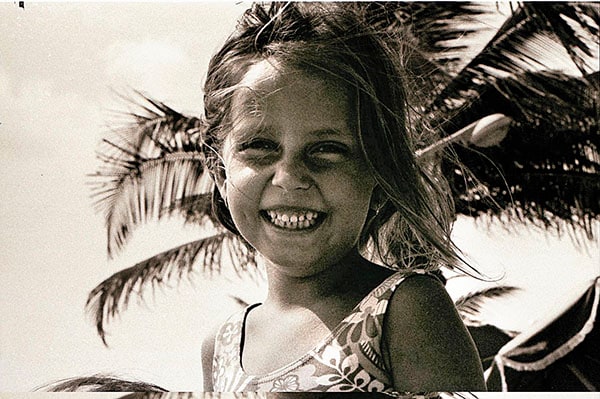

Image courtesy: Sanjna Kapoor

Shashi Kapoor’s daughter wanted to be an actor since she was a child

But I know that if my dad could earn money just from theatre, he would do theatre all his life,” she says. Shashi Kapoor, who began acting as a young boy with Prithvi Theatres and received the Dadasaheb Phalke Award in 2015, also made it a point to channel the money back into producing the kind of cinema that he liked, with films like Junoon (1979) and Kalyug (1981)—both directed by Shyam Benegal. “I respected the fact that he put money back into films that he loved, although they did quite badly. He also put money into building Prithvi. So I forgave him all the nasty films that he acted in,” says Sanjna, as her laughter returns.It was in 1990, following her stint in New York, that Sanjna began to play a more active role at Prithvi. She did so, admittedly, “with great trepidation”. The legacy that she was an heir to was terrifying. “It was enriching in every way, but it was also scary.”

Sanjna, who was only 23 at the time, did not have any experience of running a theatre. What made it even more daunting was the fact that her mother had once run it. “I grew up with stories from Satyadev Dubey (actor and playwright) and Vinod Doshi (businessman) who had been around when my mum ran it for the first five years.” Jennifer, for instance, would talk to directors after the play was over, and give them feedback. “I didn’t do that,” says Sanjna. Instead, she did what came naturally to her: Building things.

“What we succeeded in doing there was creating a hub, an adda,” she says, giving the last word the emphasis that a theatre haunt deserves. When Prithvi first opened, Tyeb and Sakina Mehta ran its art gallery for a year. Sanjna revived that. “She was also instrumental in supporting new talent,” says writer-director Makarand Deshpande. “Back then, Prithvi would have a huge round of platform performances. They would happen outside Prithvi in several languages: Gujarati, Hindi, Marathi, even Sanskrit.”

Her time at Prithvi also included an attempt to revive the travelling theatre format in which it originally existed. “That was always my mother’s dream, to have a travelling company. But it was something I wasn’t able to really ignite,” she admits. But it wasn’t for want of trying. “We did The Boy Who Stopped Smiling (a children’s play by Ramu Ramanathan), which did 200 shows. We also did Gaslight and Who’s Afraid of Virginia Wolf, directed by Rajat Kapoor.”

By 2002, Sanjna had been at Prithvi Theatre for about 12 years. It was then that she met Sameera Iyengar, a PhD in theatre from the University of Chicago (Sanjna was pregnant with son Hamir at the time). They had met once before, so Iyengar reintroduced herself. “I told her that I was looking for a job. She asked me what I had studied and I told her. She then said: Why don’t you come to Bombay? I said: You give me a job and I’ll come.” And she did. This would prove to be a “fortuitous” meeting. Iyengar had joined Prithvi at a time when Sanjna had begun to feel isolated. “Not always, because there were people I could talk to and bounce ideas off. But in that year (2013), I was feeling particularly alone,” says Sanjna.

It was also Prithvi Theatre’s 25th anniversary. Sanjna took the occasion as an opportunity to introspect. “Prithvi was built with a purpose. A purpose to improve engagement with theatre,” Sanjna recalls. “So I had all these questions: Had we done all that? Had we created an audience that was discerning or had we lost that audience?” This was also a time of rapid modernisation and there were repeated mentions of how Mumbai would become the next Shanghai. “Suddenly one was getting jhatkas about what people in power were trying to do to my city! I needed to claim my place here.” It brought about a change in her perspective, the implications of which, though not immediately apparent, would be significant.

There’s a tiger painted on a window which is hard to miss when you enter the compound of Sanjna’s house. The house is adorned with paintings depicting the tiger in sundry hues and shades. Valmik Thapar, Sanjna’s husband, is one of India’s best known tiger conservationists and has written 28 books about the jungle cat. “He has tried to build an ecosystem for the tiger,” she says.

In that, there are some fundamental points of convergence with her line of work. In 2011, Sanjna left Prithvi to embark on the appropriately named Junoon (which means passion) to create a sustainable ecosystem too: Hers, however, is for the arts. Junoon was founded by Sanjna and Iyengar, and was, in many ways, born out of the feeling of isolation that she had felt all those years ago. Back in 2003, the annual Prithvi Theatre Festival had led to the creation of India Theatre Forum, a coming together of theatre people from across the country. Several experiments followed in the form of engagements with communities in places like Chembur and Dharavi in Mumbai, where people could experience and engage with theatre. “Where Sanjna and I matched really was in the desire to celebrate and share the richness of theatre in its multiplicity with its audiences,” says Iyengar. “With Junoon, the greatest joy is that we’re contributing to building a world where people must recognise that they have a need for theatre and the arts,” adds Sanjna.

With Mumbai Local, it invites artists to monthly “addas” where they share their experiences with audiences who can attend for free. Through its Arts At Play With Schools, Junoon offers a week-long programme in which students engage with a variety of art forms and interact with artists this is present in 10 cities now.

This year, Junoon also intends to help enable local institutions to become better equipped to continue with these projects. “She has great organisational skills,” says Benegal, who is an advisor to Junoon. “What she has proved herself to be is a great cultural entrepreneur.”

The tag fits. While she is conscious of the business aspect, and insists on having an asset light model for the organisation, Sanjna measures success through people and how they’re affected by Junoon. “What we’d love to see are sharing opportunities like Mumbai Local, which allows artists to engage with people, sprouting in other places. In 10 years from now, we need to be able to say: Wow! That really worked.” In pursuit of these goals, the true assets that Junoon has, says Sanjna, include “the incredible community of artists across the country”. Image courtesy: Sanjna Kapoor

Image courtesy: Sanjna Kapoor

Sanjna interacts with children, a key audience for her

Her other major goal is born out of a sense of disappointment in the fact that though Prithvi Theatre was and continues to be a success, few have been able to replicate its model. It continues to trouble her. “One day I’m going to crack it,” she says. For now, a programme called Smart (Strategic Management in the Art of Theatre), under the umbrella of the India Theatre Forum with Junoon and the India Foundation for the Arts as managing partners, is in place as a capacity-building programme for theatre groups. With Iyengar as its director, the four-month-long course is an attempt to provide management skills relevant to their field, and help people run their theatres better.

I ask her what an ideal world would look like from Junoon’s perspective. She pauses for a moment. Then says, “That would look like every neighbourhood, every ward, in urban India with a gallery, a theatre, an art studio and books. And you’d have access to all these wonderful things. Not just access, but the possibility of creative engagements.”

For a long time, Sanjna had trouble articulating why what she did was important. “I would go to meet sponsors for Prithvi and I would get tongue-tied because I didn’t have the wherewithal to begin to say what I was doing was important and why they needed to take it seriously.” That problem no longer exists—clearly.

And it all comes back to junoon.

It isn’t hard to see that theatre is personal for Sanjna Kapoor. Be it the memories of her parents planning and building Prithvi Theatre—and her sleeping in its back rows. Or travelling in a yellow Citroen through Ireland with her grandparents, and acting with them. It is also an intimacy that, for her, will only grow by sharing.

First Published: Jun 18, 2016, 06:30

Subscribe Now(This story appears in the Dec 03, 2010 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, Click here.)