Reinventing the Indian horror film

With international collaborations and more filmmakers experimenting with the genre, the Indian horror movie is ready for an aesthetic and thematic overhaul

(Clockwise from left) Creature 3D (2014) was marketed as India’s first ‘real’ creature horror film Phantom Films has tied up with US horror movie production company Blumhouse Productions to produce 10 horror films in Indian languages Shyam Ramsay’s Neighbours was the first Ramsay film to be set in a city a poster of Akam, a psychological thriller

(Clockwise from left) Creature 3D (2014) was marketed as India’s first ‘real’ creature horror film Phantom Films has tied up with US horror movie production company Blumhouse Productions to produce 10 horror films in Indian languages Shyam Ramsay’s Neighbours was the first Ramsay film to be set in a city a poster of Akam, a psychological thriller

“What better way to learn of a place than through its ghosts?” asked our cheerful guide as he led us on the midnight ‘ghost tour’ of the university town of Lund in Sweden. We were a group of 20, mostly filmmakers, attending the Lund International Fantastic Film Festival. Some were chugging the local brew from bottles labelled ‘a bloody beer’ that were available after the 9 pm screening of The ABCs of Death. My film, Akam, a psychological thriller that fell on the outer edge of the spectrum of horror was the only Indian film being screened that year, 2012.

During my stay, I had given the inevitable interviews and participated in discussions as a representative of the horror film circle in India, but I was clearly standing on the outside looking in. “So what’s the Indian equivalent of Halloween?” an American Indie filmmaker asked me. “I don’t think we celebrate fear that way,” I offered diffidently. Earlier in the day, a colleague had sent me links to two films, both called Dracula 3D, that were releasing in 2012. The first was by legendary Italian filmmaker Dario Argento, and the second by Malayalam director Vinayan. The international horror community panned the former: Argento was only rearranging tired tropes the film wasn’t bad enough to be good and so on. But they didn’t quite know what to make of the latter. Dracula was sweating it out in tropical Kerala in a tux and cape, stakes and crosses vying with cobras and occult paintings. Was it homage, pastiche or parody? There was no frame of reference.

“A majority of the entertainment trade industry and audience still do not appreciate genres and sub-genres,” says Vishesh Bhatt, director at Vishesh Films, owned by his father, producer Mukesh Bhatt. For the most part, horror in India skims over the labyrinth of sub-genres such as slasher, possession and haunting, vampires and zombies, to name a few. And like Chinese food, these local offerings have a loyal army of fans, which does not seem to care how a film measures up to global standards or the “purer” form of horror. “The important thing is to insert horror into a good Bollywood film. That could alienate the international horror community, but it is the differentiator that brings in domestic revenue,” says Vivesh.

There’s also the pressure to conform, but it’s slowly easing. The typical Indian film, be it horror, tragedy or romcom, is around two-and-a-half-hours long with five elements: Introduction, song and dance, romance, fight and conclusion (not necessarily in that order). Until recently, it was challenging to find exhibitors and buyers for films with durations under 135 minutes. This additional half-an-hour is almost always dedicated to songs and stirred with commercial masala till the horror thread becomes incidental rather than definitive. That could, however, change with international production houses investing in Indian genre films.

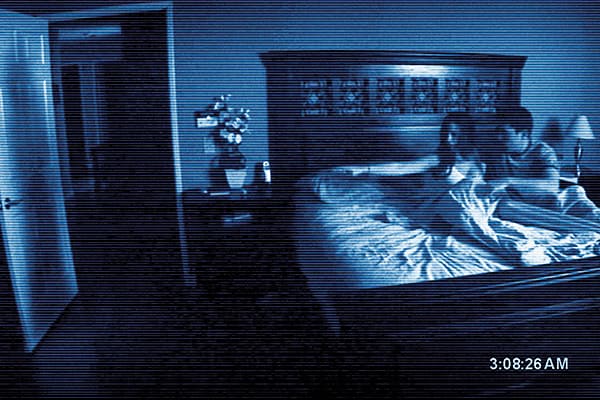

In 2014, Phantom Films—founded by directors and producers Anurag Kashyap, Vikramaditya Motwane, Madhu Mantena and Vikas Bahl—tied up with the US horror movie production company Blumhouse Productions to produce 10 horror films in Indian languages. Founder Jason Blum, who is credited with turning the $15,000 Paranormal Activity into a $193.4 million blockbuster series, is hailed as the pioneer of micro-budget horror. As the name suggests, micro-budget refers to a high-concept, one-location film, made on a budget of under Rs 26 lakh. Such collaborations could lead to an aesthetic overhaul of the Indian horror film.  Paranormal Activity, a $193.4 million blockbuster series, is hailed as the pioneer of micro-budget horror

Paranormal Activity, a $193.4 million blockbuster series, is hailed as the pioneer of micro-budget horror

For one, micro- and low-budgets necessarily call for a trimming of flab. Deprived of music as a crutch, directors will have to turn to thematic and stylistic innovation to sell their films. Another streaming avenue is alternative distribution systems and exhibition platforms like YouTube and Netflix, which also allow for shorter productions. The films produced under the Blumhouse-Phantom banner will be made accessible to not just fans within the country but also a global audience.

This Indo-US collaboration reflects a growing demand for horror in India. Today, every major production house in the country is scouting for horror scripts. The economics behind horror movies is simple: Low investment and high returns. With this year’s big productions like Bombay Velvet and Detective Byomkesh Bakshy! not causing so much as a ripple at the box office, producers are looking for low-risk investments to stay afloat. Spreading ten-figure budgets across 10 or even

20 small-budget horror films minimises risk.

And sometimes, the director just might hit the jackpot. One of the biggest Tamil hits of 2015 is the horror film Maya. Made on a budget of about Rs 12 crore, it ran to packed houses, and by the fourth week, had collected over Rs 30 crore. This story, about a single mother and her child being haunted by a supernatural entity, underscores the fact that in India, horror is linked to the foundations our society is built on: Family.

The ghost stories of a culture give insights into what its greatest preoccupations are. Right from Mahal (1949), the first horror and reincarnation film in India, our tales from the dark have dealt with threats to the family structure. The film, starring Ashok Kumar and Madhubala, tells the story of the love of a man for a ghost. At the stroke of midnight, her haunting song, ‘Aayega Aane Wala Aayega’ lures him away from his wife. Never once in the two years of their marriage does he lift her bridal veil or see her face. Unable to compete with the singing spectre, the wife commits suicide. Mahal featured seven songs and is the film that propelled Lata Mangeshkar to stardom.

Melodrama, the favoured dramatic form of Indian cinema, places the family at the centre of the narrative. Even films that spoke of social issues such as caste violence and deforestation had to fit themselves into this framework of family drama. For instance, Gehrayee (1980) by Aruna Raje and Vikas Desai, which is perhaps the only Indian film based on the Chipko movement of the 1970s, also adhered to the tenets of family life. Set in Bengaluru, it begins with the head of an upper middle class landlord, Chennabasappa, selling a plot of land in rural Karnataka to a factory owner. He returns home, indifferent to the plight of the plantation workers, especially his loyal manager, Baswa, who likens Chennabasappa’s selling of the land to allowing his mother to be raped. His anguish finds echoes in the film when a spirit possesses Chennabasappa’s teenage daughter and the family is tossed into turmoil. The façade of the perfect home is ripped apart as she blurts out scandalous secrets about her family.

In a country like India where mainstream cinema homogenises cultural identities, horror is a genre whose pivotal characters are the marginalised. Monsters, like jesters, are the ‘others’ who are allowed true commentaries. “The Telugu film Punnami Naagu (1980), about a shapeshifter who turned into a snake on full moon nights, explored the indigenous problems of the snake charmer community in a post Colonial world,” says Mithuraaj Dhusiya, assistant professor of English literature at Hansraj College, Dehi University. (He has submitted his PhD on gender in Indian h0rror films.)

In the Tamil film Kanchana (2011), the hero Raghava is possessed by three spirits, one of which is that of the transgendered protagonist Kanchana. “It is the first Indian horror film to deal with the becoming of transgendered subjectivity,” writes Dhusiya, in his essay ‘Let the Ghost Speak: A Study of Contemporary Indian Horror’. Raghava’s character is unemployed, parasitic and cowardly, a contrast to the usual macho hero of mainstream Tamil films. But this is not the case when he is possessed by Kanchana, who is played by Sarath Kumar, a Tamil star known for his alpha male roles. “It is significant that Kanchana is a Tamil film, as Tamil Nadu has been at the forefront of transgender reforms, with an exclusive welfare board, ration cards, and the facility for aravanis (transgenders) to get free sex-change operations at state government hospitals. Gehrayee is based on the Chipko movement of the 1970s

Gehrayee is based on the Chipko movement of the 1970s

Raghava’s willingness to allow his possession by these spirits can be metaphorically read as the building of a sensitive community that identifies, acknowledges and fights for the rights of non-normative sexualities—in this case, the transgender community,” notes Dhusiya. Actor Ajay Devgn, who has built his career on action movies, has bought the rights to the film in Hindi. Though thematically bold, the film follows the dictates of mainstream productions complete with song and fight sequences.

Tellingly, horror as a genre was most popular during the Emergency in the mid-1970s and its aftermath. Mainstream Indian films, caught in the throes of censorship, spewed out tales of angry young men who rebelled against generic, oppressive authority figures. Tiffinbox Films, a film factory set up by the Ramsay Brothers in 1972—which, in its heydey, specialised in assembly line production of low-budget films—became the byword for horror. The genre is pop culture’s challenge to existing market hierarchies, which could perhaps explain its current resurgence.

The Ramsay Brothers, like their subjects, existed outside the system and they realised early on that their monsters were their stars. They cast actors who were on the fringes of the Hindi film industry and created a neat inversion of the existing star system. This not only cut production cost, but also paved the way for a viable alternative exhibition system. Their films ran to packed houses in tier-II and tier-III towns with minimal promotional expenses.

In fact, the last few years have seen a slow and steady shift of horror, from small towns to cities. In the last decade, filmmakers catering to such markets have found a new audience: Big city fans of kitsch and camp, who download or stream these movie online. Of his penchant for B- and C-grade horror movies, Aseem Chandaver, executive producer of entertainment and film production house Eros Now, says, “I used to watch them ironically. Then, I realised that these were serious filmmakers who just didn’t have the money. You find some of them refreshingly unique thematically and style wise.” He cites Bhoot Ke Peeche Bhoot (2003), a thriller about one ghost battling another to save a human it is in love with. He says there haven’t been too many B- and C- grade horror movies of late. “Most have moved into sleaze, and sleaze by itself is boring.”

While it’s often difficult to remove sleaze from horror, the turn of the century saw more well-known and mainstream actors experimenting with the genre. Vikram Bhatt’s Raaz (2002) starred model-turned-actors Bipasha Basu and Dino Morea. “When I joined the set of Raaz as an assistant director at 16, I remember people telling my dad that horror was not a genre for respectable production houses,” says Vishesh Bhatt, under whose banner the movie was made. “I guess the success of the film shows that we managed to mainstream it to A-grade.” Inspired by the Hollywood supernatural thriller What Lies Beneath, the film made four times its production cost of Rs 5.25 crore, and is one of the most successful franchises today with Raaz 4 under production.

A year after Raaz, director Ram Gopal Varma released Bhoot, with A-listers Ajay Devgn and Urmila Matondkar as the protagonists. It was also the first film to successfully situate horror in the urban Indian landscape. Unlike Raaz, which was set in a forest in Ooty, Bhoot is about a couple, Swati and Vishal, who move into an apartment where the spirit of a previous tenant possesses Swati. “Horror is when each member of the audience thinks this could happen to me,” says Varma. “I wanted to break away from the clichés of a haunted bungalow on a hill and set it in the middle of the city in an apartment building.

The imagery of a car park in the basement, a lift shaft and every day objects like a TV set or a refrigerator assume supernatural significance in the context of a horror film.”

This was symptomatic of a larger shift in Hindi cinema. With the rise of the multiplex, the target audience increasingly was someone in a city, with a car, who enjoyed the mod-cons of a newly liberalised economy. The audience of this new brand of horror was no longer from small towns.

But there is no one-size-fits-all and horror, like any other genre, is subject to the whims of the audience. Last year, Shyam Ramsay made Neighbours, the first Ramsay film to be set in a city. Inspired by the Twilight series and in search of a new audience, he set out to make the first vampire film in India. It sank without a trace. Vikram Bhatt’s Creature 3D (2014), starring Bipasha Basu, was marketed as India’s first ‘real’ creature horror film. The story about a resort owner who has to battle with the eponymous CGI-generated ‘creature’ to stay in business (or alive) released to empty houses. Their respective daughters, Saasha Ramsay and Krishna Bhatt, assisted them.

As markets and styles change and mantles get passed on, it is timely to introspect on the challenges faced by the makers of Indian horror films. “I think the difference is time,” says Chandaver. “The subjects may be ambitious, but filmmakers don’t give themselves the time to do justice to the subject.” The lack of good practical effects studios is also an impediment that affects the quality of production. In the ’70s and ’80s, Hollywood mastered practical effects classics like The Exorcist (1973), The Evil Dead (1981) and The Shining (1980) drew filmmakers all over the globe to the genre. In the absence of such studios in India, the Ramsay brothers imported masks and phantom limbs fabricated from latex and foam. It changed the look of the indigenous ghost our yakshis and pisachus had light eyes and vampiric fangs.

We seem to have made the quantum leap to CGI without experimenting on actual production, thus having to rely on established imagery and styles of the West and Southeast Asia. Though our horror aesthetic remains informed by the hand-me-downs of Western gore, our monsters do not have to follow the rules. Zombies can disappear and vampires could be killed with mantras. Exorcism scenes will often include the iconography of multiple religions.

It doesn’t help that India has not traditionally hosted genre festivals and few Indian programmers curate for them abroad.

Image: Rohan Sabharwal

Image: Rohan Sabharwal

Scores of cinema lovers attended a horror film festival held at The Hive in Bandra, Mumbai, a few months ago

Internationally, most successful horror films are discovered at such festivals. “It is quite difficult to follow the Indian production from afar. Without an insider or the opportunity to attend Indian events, we have only a glimpse of the annual local production,” says Anais Nin, artistic director of Switzerland’s Neuchâtel International Fantastic Film Festival. “But curiosity about Indian films is growing really fast in the festival circuit in Europe,” he adds.

One positive outcome of the growing popularity is the recently emerging space for genre-specific festivals. A few months ago, I attended a horror film festival held at The Hive in Bandra, Mumbai. It was screening a curated package of horror shorts of which there were no Indian films. The hall was packed with 20-somethings sitting on metal chairs or lounging on mattresses strewn on the floor. The organisers, short film aggregators Short Film Window, say the turnout was one of the largest they have had at The Hive.

In a significant move, this year, the Jio MAMI Mumbai Film Festival has included an ‘After Dark’ section for horror and genre films to be curated by Jongsuk Thomas Nam, festival consultant of the Bucheon International Fantastic Film Festival and managing director of its film industry programme, Network of Asian Fantastic Films. “Horror will be taken seriously in India only if credible filmmakers like Sanjay Leela Bhansali start making and endorsing it,” says Chandaver.

With international collaborations and more directors turning to this genre, 2016 could well be the year when Indian horror will come into its own.

First Published: Dec 24, 2015, 07:10

Subscribe Now(This story appears in the Sep 10, 2010 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, Click here.)