Labels and rebels in Anees Salim's novels

Books highlight subtle ways in which people are defined by a traditional belief system

When I say that one of the funniest words I have encountered in a recent Indian novel is ‘Franklin’, further explanation is clearly required. In Anees Salim’s marvellous Vanity Bagh—narrated by a young man named Imran, who lives in the Muslim colony that gives the book its title—a tree standing opposite a mosque is called Franklin, after the priest who planted it a century earlier. “The mohalla-wallahs are so obsessed with spinning yarns and naming things that they haven’t spared even this tree,” Imran tells us early in the book. But having provided this disinterested commentary, he himself continues to refer to the tree by its name. Soon I was grinning at every occurrence of a throwaway line like “we were idling our time away by Franklin” or “under Franklin stood Mary Pinto, seriously irritated”.

But there are deeper resonances to Imran’s remark about the naming or defining of things. He and his friends have the names of famous Pakistani politicians or cricket stars: “The mohalla-wallahs always named their children after people with successful professions.” And as he tells his story—including the sequence of events that leads to his group becoming pawns in a terrorist act—he adorns the text with little things said by various people, presented as quotations, complete with their name at the bottom and their year of birth and death in brackets. If the quote is from someone whom Imran doesn’t know enough about, the dates are naturally missing, but the brackets stay like this:

“If this city had a WTC, they would have bombed it as well”

– Public Prosecutor ( – )

Imran’s obsession with numbers and dates is clarified later in the book: We learn that he tries to make sense of things and people by giving them finite shape and meaning and a back-story. At a broader level, this idea can be extended to the terrain of religion, which is an unavoidable presence in this story yarn-spinning and labelling done by people thousands of years ago has created a situation where two human colonies in the same city, located just minutes apart, might come to see each other only in terms of their singular Hindu and Muslim identities. (If Vanity Bagh, nicknamed Little Pakistan, is the Muslim colony in the book’s unnamed city, its nemesis is a Hindu neighborhood called Mehendi.)

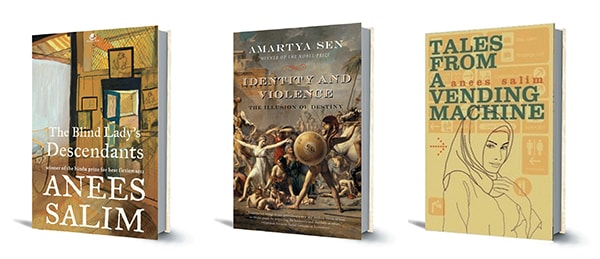

In Identity and Violence: The Illusion of Destiny, Amartya Sen noted the hazards of “a solitarist approach to human identity, which sees human beings as members of exactly one group”. That each of us contains multitudes—we can be many different things at the same time, surprising others and ourselves in the process—is a central theme of Sen’s book. And it is an important current in Anees Salim’s work, over the four novels that have made him one of the most notable voices and one of the outstanding storytellers in contemporary Indian writing. Salim’s last three books—Vanity Bagh, Tales from a Vending Machine and The Blind Lady’s Descendants—feature lower-middle-class Indian Muslim protagonists and chronicle the minutiae of their lives, including things that get lost in the mainstream narratives and clichés about the community. He depicts cultural confusion with amazing lightness of touch, since his focus is on multi-dimensional people rather than on big statements and because he is effortlessly funny even when telling sad stories.

In The Blind Lady’s Descendants, the melancholy narrator Amar is an atheist in pointed contrast is his staunchly religious brother Akmal, who earnestly tells stories about Neil Armstrong hearing the call of the muezzin when he set foot on the moon. Amar and Akmal can be seen as representing two faces of the modern Muslim, but Salim doesn’t hold them up as symbols. And the reader has to come to terms with this. When Amar casually mentions having felt up his cousin Razia when she was 11 and he 13, it comes as a minor shock, not just because this offhand raunchiness marks a shift in the book’s tone, but because on some subconscious level I was still thinking in stereotypes I was thinking of these characters as Good Muslims in the sense of being respectful of bonds and distances and veils, and forgetting that they are human beings with the same impulses as anyone else.

The people in these stories are sometimes constrained by their larger identities even as they try to break away from them, and this tension is the warp and weft of their lives. Many of those quotations that dot the pages of Vanity Bagh are from films starring Sean Connery or Chuck Norris here is an imam’s son living in a conservative setting, whose thoughts are shaped by movies from a country that would, in many ways, be antagonistic to his family’s way of life. Similarly, in Tales from a Vending Machine, the young narrator—a spirited, winsome, occasionally muddled girl named Hasina, who works at an airport vending machine—reads a lot and wants to lead a modern, self-reliant life she day-dreams about battling a terrorist who tries to “kidnap” the plane she is piloting. But, she also weeps when she hears of the execution of Saddam Hussein, thinks of the destruction of the Twin Towers in terms of an exciting film, with “the top of the building crumbling smoothly to the ground like a wedding cake”, and—in one of the book’s most uproarious scenes—reflexively yells “Allahu Akbar” back at the fake terrorist who has accosted her during a mock drill at the airport (all that Hasina was required to do was slump over and play dead).

The breeziness of this scene doesn’t mask the question it raises: In this scripted attack, why are the ‘terrorists’ cast as purdah-wearers who shout “Allahu Akbar” before attacking? In telling these stories about lower-middle-class Muslims (including some who mock their faith and its rituals, but also feel defensive about their culture in specific situations, much like the hero of Mohsin Hamid’s novel The Reluctant Fundamentalist), Salim shows how a particular world can become both a cage and a sanctuary. What happens when the boundaries of what you can and cannot do are pre-determined by people in authority and when this in turn creates a vicious circle because people on the outside are constantly judging you?

These books are about the subtle ways in which people are defined by a traditional belief system, while also, briefly at least, transcending those systems. And about the messy complexities of human lives. For all the cataloguing and classifying in Vanity Bagh—all the neat attempts at ordering the world—you have to think how odd a name Vanity Bagh is for a Muslim colony, or Franklin for a tree waving its leaves at a mosque.

The author is a Delhi-based writer and journalist

First Published: Jun 09, 2015, 07:19

Subscribe Now(This story appears in the Jun 18, 2010 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, Click here.)