Film festivals in the time of conflicts

Citizens use cinema to reclaim their life, culture and civilisation

What happens when cinema leaps off the screen and becomes a part of life itself? All over the world, cinema has been used as an active instrument of defiance, of refuge from war, of peace and friendship without borders—born of an insistent belief in a sane, cultured and civilised world, beyond guns and bombs. There are numerous instances of cinema as a raised middle finger, including the Sarajevo Film Festival born in the midst of the Bosnian war the Krok International Animated Film Festival jointly held by intermittently warring Russia and Ukraine and the ImagineAsia festival, held by the British Film Institute, which used film to address racial violence in the UK.

The Sarajevo Film Festival was born in 1993, amid snipers and artillery fire, during the four-year siege of Sarajevo by Bosnian Serbian troops. Sick of cowering in homes and bunkers in paranoia for months, a few friends decided to put their lives on the line to watch and discuss films together. And a film festival was born. On attending it, I realised the festival was a powerful act of defiance, with citizens using cinema to reclaim their life, culture and civilisation. Mirsad Purivatra, festival director and co-founder, calls its origins “war cinema”.

“Why are you holding a film festival in the middle of a war?” a reporter asked Haris Pasovic, director of the first edition of the film festival. “Why are they holding a war in the middle of a film festival?” he retorted. In his article, titled ‘Made in War: The Sarajevo Film Festival’, on the European Cultural Foundation website, scholar Mirza Redzic offers inspiring insights into the birth of the festival. There was hardly any electricity, heating, running water or food rations. A small theatre stage in the Dramatic Arts Academy was transformed into a ‘cinema’ through a VHS player and projector. The festival ran on the sheer willpower of the organisers, audiences and generators: Thirty-seven movies were screened for 15,000 besieged residents. Their absolute audacity drew worldwide support. Directors Francis Ford Coppola, Wim Wenders and Krzysztof Kieslowski shared their films, while Alfonso Cuaron and Leos Carax turned up for Q&As. Photographer Annie Leibovitz designed the festival poster and Susan Sontag brought the posters, printed in New York, via a UN airlift. Journalists with UN press cards brought VHS tapes of films for the screenings.

As the Bosnian currency collapsed, Redzick reveals, the price of a ticket was seven cigarettes. But for the people of Sarajevo, the festival was a source of great optimism. The screenings were full, with audiences risking their lives just to see a film. Over 10,000 people were killed in the war, and over 50,000 wounded, including civilians. Yet, so fiercely determined were Sarajevo’s artistes to fight for their art that, along with the film festival, an estimated 182 plays, 170 exhibits and 48 concerts were staged during the siege.

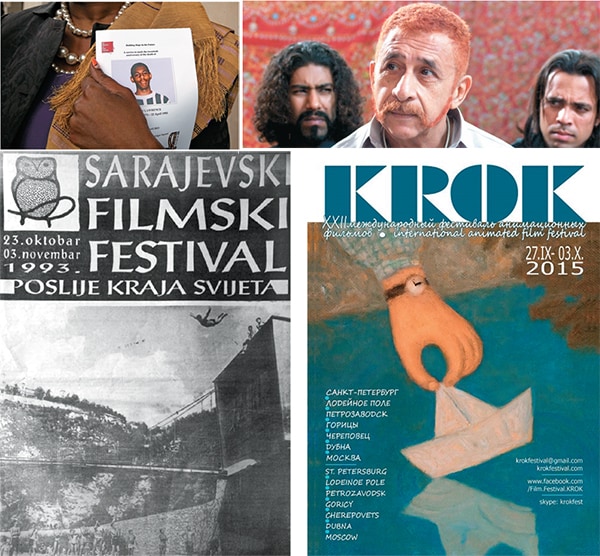

Pictures of protest: (clockwise from left) A picture of black teen Stephen Lawrence, whose murder triggered a wave of cultural initiatives to address racism in the UK Meenu Gaur and Farjad Nabi’s Zinda Bhaag is an excellent example of Indo-Pak collaboration Posters of the Sarajevo and the Krok film festivals

Pictures of protest: (clockwise from left) A picture of black teen Stephen Lawrence, whose murder triggered a wave of cultural initiatives to address racism in the UK Meenu Gaur and Farjad Nabi’s Zinda Bhaag is an excellent example of Indo-Pak collaboration Posters of the Sarajevo and the Krok film festivals

A similar defiance continues east of that continent. Russia and Ukraine have been at war for centuries, and attacked each other again in 2014 and 2015. But the Krok International Animated Film Festival, held on water as if to ‘liquidate borders’, is jointly organised by both nations. It takes place on board a cruise ship that, by turns, cruises in Russia (along the Volga) and Ukraine (along the Dnieper and the Black Sea). Its 22nd edition is scheduled to travel from St Petersburg to Moscow over a week in September and October this year. The Krok festival believes that life is grand, that some people would much prefer to celebrate art, make friends and enjoy life, while refusing to be held hostage by those who would rather kill each other. The festival’s guests this year include India’s brilliant animation film director Gitanjali Rao, whose Printed Rainbow won prizes at the Cannes film festival. There’s a jury and all that, but the essence of the festival is elsewhere—everyone gathers to watch movies, eat, drink, dance, hop off to visit new ports and get on board again, till the end of the festival.

The story goes that despite the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, the closely linked Russian and Ukrainian animation film industries refused to turn into enemies overnight. So filmmakers continue their camaraderie, thanks to the cinematographers’s unions of both nations backed by their respective ministries of culture.

On the other side of the continent, in the UK, film has also been used to address racist violence. The racially-motivated murder of black teenager Stephen Lawrence in 1993 provoked institutional changes to address racist attitudes in the police, law and judiciary, as well as the public. ImagineAsia, organised by the British Film Institute (BFI) in 2002, was partly a cultural initiative to improve race relations by influencing perceptions of the other. It was a massive film festival, with 650 films, exhibitions and events, held with 70 partner organisations across the UK. The BFI also specifically includes cultural diversity as part of its core values and policy.

Closer home, there are many examples of Indo-Pakistani cultural confluence, including in cinema. The films include MS Sathyu’s Garm Hava, Govind Nihalani’s teleserial Tamas, Mehreen Jabbar’s Ramchand Pakistani (with Nandita Das), Shoaib Mansoor’s Khuda ke Liye (with Naseeruddin Shah), and Zinda Bhaag. The last film is an excellent example of cross-border collaboration. A Pakistani film, it is co-directed by Meenu Gaur (India-born) and Farjad Nabi (Pakistan), and produced by Gaur’s husband Mazhar Zaidi (Pakistan). It features Pakistani talent Khurram Patras and Amna Ilyas, as well as Naseeruddin Shah, cinematographer Satya Rai Nagpaul and editor Shan Mohammed from India. Zee, whose Zindagi channel airs Pakistani serials, now has a ‘ZEEL for Unity’ project, for which it has commissioned six Indian and six Pakistani directors to make films. There’s also Supriyo Sen’s delightful film Wagah, about a small boy on the Wagah border, who makes a living by selling propaganda CDs to aggressive patriots, but yearns to fly kites with kids across the border. Perhaps the peaceniks need to strategise like the hardniks.

The writer is South Asia Consultant to the Berlin Film Festival, award-winning critic, curator to festivals worldwide and journalist

First Published: Oct 13, 2015, 06:55

Subscribe Now(This story appears in the Aug 13, 2010 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, Click here.)