Bhupen Khakhar and the art of criticism

Tate Modern's Bhupen Khakhar retrospective may be in danger of being hijacked by critics high and low, but the artist's relevance cannot be undermined by the noise

Everybody loves a good spat, especially when it plays out in public. Though skirmishes between artists and critics are rare, that does not mean such run-ins do not happen. Gulam Rasool Santosh and Keshav Malik fell out over the latter’s review of Santosh’s tantra works J Swaminathan riled the entire establishment as a firebrand critic FN Souza was irreverent when it came to reviewing his peers’ work, even though he did so privately or after a generous tot or two, when he was at his lucid and waspish best.

Criticism draws blood too often, and in this day of blogs and trolls, it has lost much of its reasoned debate and elegance. This is what happened when Jonathan Jones, a British critic writing for The Guardian, raised the hackles of the (admittedly, largely Indian) art establishment when he questioned, drawing parallels with racist reference, the selection of Baroda artist Bhupen Khakhar’s retrospective that opened at the Tate Modern in London in June (and will be on display till November 6 this year). “What makes this an odd exhibition for Tate Modern to put on is that Khakhar so strongly resembles the kind of British painter it would never let through its doors,” Jones wrote.

Here, it is important to point out a distinction between two of London’s more important art establishments, Tate Modern and Tate Britain. The latter is seen as a subaltern establishment devoted to historical portraits, landscapes and the kind of art that was made in the continent from the late 16th century to more recent times. The former is an ode to international modernism of the current and previous centuries, and its selections and curations attract both admiration and opprobrium in equal measure. Jones seems surprised that while comparable British artists such as David Hockney (to add insult to Jones’s injury, Khakhar is often described as India’s Hockney), Howard Hodgkin and Frank Auerbach have had to make do with retrospectives at Tate Britain, Khakhar should be honoured at the more esteemed Tate Modern.

Such provinciality is not entirely unusual and, responding to it, Indian art writer Geeta Kapur heaps as much scorn on Jones as he does on Khakhar. Where Jones observes Khakhar as “incredibly unimpressive”, his subjects “drab and vague”, his paintings “big and boring”, his work of “archaic mediocrity”, Kapur attacks Jones for his lack of “interpretive agility”, mentions his use of “alliterative adjectives that are mostly expletives”, and castigates his painterly search for “pedigree being a trait still cherished by the English, when their own identity holds little conviction”. How did this slugfest come about? When curators Chris Dercon and Nada Raza planned their retrospective, You Can’t Please All, at most they would have expected appreciation for an Indian artist who is mostly, and unfortunately, known as a gay icon for investigating his own, alternative sexuality in his paintings, when his contribution across genres has been seminal. The accountant-turned-artist—mentored to a great extent by fellow artist and art teacher Gulam Mohammed Sheikh, with whom he published the art journal Vrischik for six years (from 1968-73)—is highly regarded in India, and his work is keenly collected.

Largely self-taught, Khakhar was born in Bombay (now Mumbai) in 1934, the youngest of four siblings and the beloved of his mother who pushed him to go to university and get degrees in economics and commerce, which he put to use in his early career as an accountant in Baroda. That short-lived phase was to end when Gulam Sheikh persuaded him to come to the Faculty of Fine Arts at Maharaja Sayajirao University of Baroda, sealing his future.

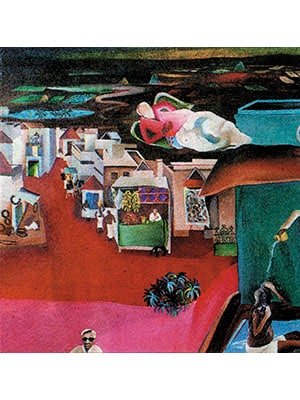

Khakhar’s paintings are described as naïf and lacking in technical finish—the very reasons they are highly prized by most—and gained from the exploratory indigenism of Baroda as well as his own investigation into Indian miniatures, both of which he combined in his sardonic, mocking figurations that drew attention to the (till then) unlikely middle-class neighbourhoods and lifestyles. His compositions used space in a leisurely manner, with shortened figures placed in often ambient spaces to build a fresh dialogue in perspectives, while retaining the epic storytelling possibilities of miniatures. Barbers, watch repairers, pavement tradespeople, community balconies, the comings and goings of neighbours—everything was grist to Khakhar’s mill and he combined the trite with the gossipy and gave it the platform of high art. Image courtesy (left): Tate Modern

Image courtesy (left): Tate Modern

'Death in the Family', oil on canvas

His own visit to London, however, left him cold, literally and figuratively, as he found the British reserved and sullen, but it helped him come to terms with his sexuality in far more expressive ways and, from the 1980s onwards, his narrative turned to gay contexts without social prejudice. His painted figures appeared awkward and crude, and the content was often risqué, but critics and collectors responded to his quest for an identity that was uniquely his own, with unusual warmth. At a time when homosexuality was taboo, this was as heroic as it was admirable, but in the end Khakhar’s work was deemed important for its own self and style rather than for its provocative commentary. Nor was Khakhar content to just paint. He wrote stories, experimented with a book that he published in an accordion-like format and was featured as a character in Salman Rushdie’s The Moor’s Last Sigh. (He returned the favour with a portrait of Rushdie—‘The Moor’, which now hangs in London’s National Portrait Gallery.)

British artist and art writer Timothy Hyman came across Khakhar’s work while a visiting professor in Baroda and wrote an eponymous book that is still regarded as the most important account on the artist. “There was a dark side to Bhupen,” Hyman noted. “He did see the emptiness of many people’s lives.” The retrospective at Tate Modern takes its name from a 1981 painting with the same name, described as Khakhar’s “coming out” painting by Hyman, and shows a nude male figure looking over his balcony at a humorous Aesop’s fable playing out, as an old father and young son alternately mount a donkey to jeering remarks from passers by, leading to the message, ‘you can’t please all’.

Writing about the exhibition (once again in The Guardian), Laura Cumming is frustrated at its “uneven, garrulous, puzzling, opaque” content because of a lack of referencing of India in the 1960s and 70s, a period when many of the displayed paintings were made. She finds the exhibition at worst “ill-edited”, at best creditworthy for its “compassionate curiosity”, but is intrigued by, and admires, the artist. Clearly, if Indians react positively to Khakhar’s work, it is because they are more familiar with his milieu than most foreigners.

Khakhar died in 2003 of cancer, battling the disease somewhat publicly through his works preceding his death. These too find a place in the exhibition. And it is these that seem to move visitors, with his earlier paintings and watercolours occupying an anthropological space as India morphs from its provincial identity to a developing superpower.

In recent years, Khakhar’s fan following has only grown and prices for his works have been rising in auctions in India, Europe and America. The keenly-awaited Tate Modern retrospective follows up on an earlier 2002 one at the Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofia in Spain that brought Khakhar into the international forefront.

If the celebrations following the Tate launch have soured somewhat in the rarefied intellectual firmament of the art community, it has made very little difference to the following Khakhar enjoys as an artist who grounds a pre-liberalised India in a distinctive, modernist perspective that can best be judged by those whose homes and hearts he lit with his questioning eye.

First Published: Aug 09, 2016, 06:49

Subscribe Now(This story appears in the Dec 17, 2010 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, Click here.)