Life after God: Markus Persson became a deity to millions in his virtual world

Minecraft's Markus Persson then abruptly took $2.5 billion and walked away. A look inside the deal of the year-and the confused, indulgent life of a fallen idol

It’s 7 pm on a Monday in Stockholm, and Markus Persson sits on the terrace of his ninth-storey office, sipping the speedball of alcoholic beverages, a vodka Red Bull. Three hours ago he committed to not drinking today, still in recovery from a 12-drink Thursday bender while nursing an ear infection. Yet here we are, embracing heavy-handed pours of Belvedere while surveying the workers in adjacent high-rises hacking away at their keyboards.

“He looks worried,” says Persson, pointing to a man in a building across the street rubbing his face and staring blankly into a computer screen.

After a few more seconds of looking at the man, Persson seems bothered by the scene and darts inside. For the better part of the last five years the 35-year-old Swede was that guy, a man who constantly stressed about his creation, Minecraft, the bestselling computer game of all time. Even calling it a game is too limiting. Minecraft became, with 100 million downloads and counting, a canvas for human expression. Players start out in an empty virtual space where they use Lego-like blocks and bricks (which they can actually ‘mine’) to build whatever they fancy, with the notable feature that other players can then interact with it. Most players are little kids who build basic houses or villages and then host parties in what they’ve constructed or dodge marauding zombies.

Truly obsessed adults, though, have spent hundreds of hours creating full-scale replicas of the Death Star, the Empire State Building and cities from Game of Thrones. The word ‘Minecraft’ is Googled more often than the Bible, Harry Potter and Justin Bieber. And this single game has grossed more than $700 million in its lifetime, the large majority of which is pure profit.

“It doesn’t compare to other hit games,” says Ian Bogost, a professor at the Georgia Institute of Technology who studies videogames. “It compares to other hit products that are much bigger than games. Minecraft is basically this generation’s Lego or even this generation’s microcomputer.”

In this virtual world, Persson—or rather his internet persona, a loudmouthed fedora-wearing crank named Notch—became a deity-like figure to millions of gamers, establishing and clarifying the rules with Zeus-like authority. But Persson is anything but an opinionated extrovert. Face-to-face he’s polite, plainspoken and private. (He rarely talks with the press.) Over time the demands and expectations of fans looking to Notch to keep the monster hit going turned him into a self-conscious wreck.

So three months ago Persson pushed it all away, completing the sale of Minecraft to Microsoft for $2.5 billion in cash. His 71 percent stake in Mojang, the company behind Minecraft, made him a new, and particularly flush, member of the Forbes World’s Billionaires list. With well over half his life ahead of him, the man who created an entire universe, whose persona was synonymous with it and who received the wrath of his community for abandoning it, must now figure out exactly who he is.

The results so far are unimpressive, as he’s mostly acted like a dog chasing cars. When Persson decided to buy a house in Beverly Hills, he went for a $70 million, 23,000-square-foot megamansion, the most expensive home ever in an enclave known for them. He’s become known for spending upwards of $180,000 a night at Las Vegas nightclubs. He and Mojang co-founder Jakob Porsér have started a company called Rubberbrain in case they think of a new game idea—but right now he can’t focus much on any.

These conversations with Forbes represent Persson’s only interview about the Minecraft deal and his life after. It turns out that the most certain thing this windfall bought him was some heavy soul-searching. The only thing he has learnt for sure: He was right to walk away from Minecraft. In explaining his recent decisions, he quotes Leonardo da Vinci: “Art is never finished, only abandoned.”

This meteoric Minecraft saga starts in the vast Swedish forest somewhere between Stockholm and the Arctic Circle, in the 4,000-person town of Edsbyn. While other children played soccer in the summer and bandy (a variation of ice hockey with a ball) in the winter, the introverted Persson tinkered for hours on end with Legos. His father, a railroad worker, brought home a Commodore 128 home computer when Persson was seven. The eager son coded his first computer program by eight.

While Persson was a good student, he found life at school difficult after his family moved to Stockholm when he was in second grade. Unable to make new friends easily, he became ever closer to the family computer, which offered entertainment like Boulder Dash, an 8-bit puzzle game, and The Bard’s Tale, an action-role-playing title. In the book Minecraft: The Unlikely Tale of Markus “Notch” Persson, Persson’s mother, Ritva, recalls periods when her son would fake stomach aches to stay home from school and while away hours in front of the computer.

The young Persson found further solace in PCs as life at home fell apart. His parents divorced when he was 12. Persson’s father abused alcohol and became addicted to amphetamines. His younger sister also began to experiment with drugs and eventually ran away from home.

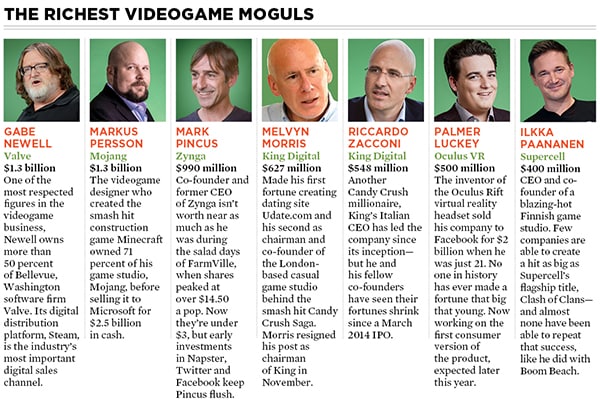

For his part Persson failed to finish high school. He was still living at home when his mother, a nurse who worked the graveyard shift at a local hospital, forced him to take an online programming course. It was a wise investment. Channelling his childhood passion, he started churning out games, and in 2004, at 24, he landed a gig at Midasplayer, later known as King.com, the maker of Candy Crush.

While there he befriended Jakob Porsér, an equally reserved young developer. “It was a great place to start,” says Porsér. “You’d be making small games in Flash, and you actually did most of the stuff in the game yourself except for the graphics.” The two began plotting their own games, some of which gained notoriety on indie game websites. His bosses were not amused. “We felt that we couldn’t have someone working for us that at the same time was building his own gaming company,” says Lars Markgren, the Midasplayer co-founder who had hired Persson.

In 2009 Persson left Midasplayer to take a programming job at Jalbum, an online photo-sharing service that didn’t mind his moonlighting. He quickly focussed his spare time on an odd-looking creation where players collect resources like wood and stone and use them to build things, from axes and shovels to houses and cities. Persson named it Minecraft and posted it in May 2009 as an unfinished piece of software on TIGSource, an indie gaming portal. Heavy on technical knowhow and light on instructions, the game’s early adopters were forced to form a community just to figure out how to play.

Minecraft wasn’t the first ‘sandbox’ construction game, nor was it the first to challenge players to gather resources to survive in a hostile world. (Players can be attacked by exploding creatures called ‘Creepers’ when night falls in the game.) But its timing was perfect, released just as a new generation of kids, too young for Facebook and Instagram but old enough to want to make things online, were getting laptops, smartphones and tablets.

By June 2010 PC users were buying 400 copies a day, at about $6 per download. Persson and Porsér quit their day jobs, and Persson even grabbed his old boss, Jalbum CEO Carl Manneh, to run the business side. They named their nascent company Mojang, ‘gadget’ in Swedish.

Minecraft’s secret weapon was Notch. More than just a nickname, Notch allowed Persson to shed his real-world introversion. Through blogs, forums and Twitter, he addressed his fans’ every question about game play, development and life. Any appearance on a Minecraft server was akin to an Elvis sighting. Notch also gave followers a figure to root for, a sharp-tongued icon in a fedora that stood up for independent game companies. Through this alter ego, Persson amassed more than 2 million followers on Twitter, loyal folks who read his diatribes against the “cynical bastards” of Electronic Arts, who deigned to release an indie gaming bundle, or virtual reality device maker Oculus VR, for selling out to the “creepy” Facebook.

Persson didn’t spend a single krona on marketing, and Minecraft grew virally, with Mojang adding Android and iOS smartphone versions that to this day rank among the top-three paid downloads in the US, according to App Annie. In May 2012 Mojang released a version for Microsoft’s Xbox 360 that sold more than 1 million copies in the first week (and 15 million copies to date). Then came the licencing agreements. Minecraft-branded apparel marketed through San Diego-based J!NX became a top seller among young fans, while books on the game became immediate bestsellers. Egmont Publishing International, which has published only a few titles on the topic, has sold over 7.5 million copies in more than 60 countries. Last year Warner Bros bought the rights from Mojang to explore the possibility of a feature film.

With only 30 or so employees, Mojang was earning profits that seemed endless. It ended 2012 with about $230 million in sales, with gross profits of more than $150 million—$101 million of which Persson paid to himself in exchange for licences to Minecraft’s intellectual property. (He quickly bought the most expensive apartment in Stockholm.)

Investors circled feverishly. Manneh says he talked with more than 100 venture firms in that time, including blue-chip Silicon Valley outfits Sequoia Capital and Accel Partners, but never considered taking money because Mojang simply didn’t need it. There was also a visit from billionaire Sean Parker, who whisked away Persson, Porsér and Manneh on his private jet for a wild night out in London. They still turned down his money.

“It was the first time we ever flew on a private jet,” says Manneh. It wouldn’t be the last. As a private company with no outside investors, the flush firm commissioned Renaissance-style oil paintings of its Mojangstas. To celebrate 10 million downloads, they took the whole staff to Monaco for three days of champagne-fuelled partying and yachting. And while the three founders held all the stock, Persson kept employees lubricated with a $3 million group bonus in 2012.

But even with the world at his feet, Persson sometimes felt like it was on his shoulders. Following Minecraft’s official release in late 2011 at the first ‘Minecon’ convention in Las Vegas, Persson stepped down as head developer, ready to explore new game ideas and life with his girlfriend-turned-wife, whom he had wed that summer.

That bliss was short-lived. Persson’s father, still battling substance abuse and depression, committed suicide before Christmas that year. With his father’s death weighing on him, Persson proceeded through daily life as a man who didn’t know what he wanted. He divorced his wife after a year of marriage. “As of today I am single: #mixedemotions,” he tweeted. And when Persson returned to work after a short sabbatical, he felt pressure to recreate the magic of his first hit.

At the same time, Persson remained the face and voice of Minecraft. It didn’t matter if he had stepped down from everyday development, Notch was still the figure players emailed for a new code modification or tweeted at if they thought something was wrong with the game. Something as minor as alterations to the mechanics of virtual boats triggered barbed messages directed at Notch, who had nothing to do with the changes. Peruse Persson’s Twitter replies or any YouTube video featuring the Minecraft creator and you’ll likely find comments like “Notch has always struck me as being a giant tool” or “Notch is a fat loser”.

“I was struggling with why are people so mean online,” says Persson. “You see the mean comments, and they seem like they’re written in a bigger font size almost.” The man who had embraced his online persona felt ensnared by the negativity it provoked. And so Persson began pondering an exit.

The way out started as nothing more than a tweet. It was June 16, 2014, and Persson bunkered in his penthouse apartment with a cold. Minecraft users had been up in arms that week about the company’s decision to start enforcing its End User Licence Agreement, which barred players from charging others for certain gameplay features, such as stronger swords. As hundreds of tweets an hour flowed in, Persson, feverish from his cold, tapped out a 129-character outburst that would change his life forever.

“Anyone want to buy my share of Mojang so I can move on with my life?” he asked. “Getting hate for trying to do the right thing is not my gig.”

Mojang CEO Carl Manneh was sitting at home with his family when he first saw the tweet. Within 30 seconds of his reading it, his phone rang. A Microsoft executive who co-ordinated with Mojang wanted to know if Persson was serious. “I’m not sure—let me talk to him,” said Manneh.

While Persson originally wrote the message as a half-joke, the realisation that he could disassociate from Mojang took hold. The man who once publicly pledged that he would not sell out to evil corporations now had his head turned. In the week that followed, Manneh’s phone rang constantly with interest from Microsoft, Electronic Arts, Activision Blizzard and others. Talks with Activision petered out. Persson, cryptically, won’t discuss what happened with EA but says that Mojang ruled out potential buyers “who did gameplay in a way we didn’t like”. Microsoft, however, apparently passed muster.

The motivator for Microsoft, ultimately, was a tax dodge. The software giant was sitting on a $93 billion overseas cash pile that it couldn’t repatriate without paying Uncle Sam his share.

So Manneh dictated the sale terms: Persson and Porsér wanted a clean break and no attachments to the company. Also, given Microsoft’s massive staff consolidation following its purchase of Nokia, no layoffs. (With just 47 employees that wasn’t a material concern for the buyer.)

Microsoft’s point man, Xbox Chief Phil Spencer, dealt solely with Manneh. Persson and Porsér recused themselves from negotiations, though Spencer did spend time, over herb-flavoured Swedish liquor, arguing with them about the direction of the gaming industry. The software giant’s CEO, Satya Nadella, never set foot in Stockholm for what remains the largest acquisition during his tenure. The Microsoft CEO only called Manneh twice to forward the talks.

While lawyers worked around the clock to close, there were few clues of the multibillion-dollar deal afoot. Microsoft kept relatively quiet, though Nadella did say in a July letter to employees that he was investing in gaming, calling it the “single biggest digital-life category, measured in both time and money spent, in a mobile-first world”.

The usually vociferous Persson remained silent, too. He spent his days chasing small ideas for new games and learning programming languages. On September 11 he wrote a blogpost detailing his work with a language known as Dart in rebuilding the earliest version of the classic shooter game Doom, though he peppered the blogpost with clues of the impending sale, using Doom as a metaphor for Mojang. “If I do move on to something new, I’m sure someone with more patience than me to see things through can take over the project,” he wrote, adding, “I can’t spend all my time tied to it.”

On September 15 Microsoft announced it would pay $2.5 billion, in cash, to acquire Mojang. Within hours of the announcement Persson would pen his final blogpost, detailing his departure from the company he created. “It’s not about the money,” he wrote. “It’s about my sanity.”

Looking back, Persson says he was expecting Minecraft’s fans to have a worse reaction to the sale announcement. “The day we announced it, I was going to shut down my Twitter [account] because I wouldn’t be able to deal with it,” he says. “But people were surprisingly okay with it. They read my explanation, and they said, ‘Okay, well I hope you take care of yourself.’”

As for going against his earlier claims that he wouldn’t sell, especially to the company that personifies Big Tech, Persson shrugs and says he can live with his $2.5 billion contradiction. “You have to be responsible for what you said, of course,” he says, “but I don’t really feel a lot of shame for saying something that I’ve changed my mind about.”

Mojang’s staff had a harder time comprehending their former boss’s dramatic shift. While they received bonuses taken from Persson’s part of the deal (Porsér for his part cleared over $300 million aftertax Manneh, more than $100 million), many felt “disappointed” and “empty” when they heard of the decision, says one employee who asked not to be named. Some still remain cold to Persson today.

“We spoilt them, and their reaction hurts me,” counters Persson. Despite that he’s managed to move on. In November, when the deal finally closed, Persson, Porsér, Manneh and Manneh’s twin brother jetted to Miami and St Barts to celebrate. Persson dubbed their little getaway “the sellout trip”.

These days Persson pays less attention to the heckling on Twitter and more to the insults hurled his way by close friends on a WhatsApp group they’ve crudely titled Farts.

The unleashed Persson has regressed toward adolescence. At the temporary office for Rubberbrain, jokes about male genitalia and laughter bounce off the ceiling and elicit annoyed floor banging from the upstairs neighbour.

Persson ignores the foot-thumped berating much like he’s done with the armchair trolls. He says he’s taken fondly to the mute button on Twitter, which allows him to tune out unkind people without notifying them that they’ve been blocked. Occasionally, though, his curiosity will get the best of him, and he’ll reply. Lately he’s been responding to his haters with a moving image from the movie Zombieland of Woody Harrelson wiping tears away with a wad of money. “I’m aware that tweeting the image is a little douchey,” he shrugs. He’s equally gauche with people he likes, broadcasting his vacations via chartered jet on Snapchat. As for girls, “I tried to use Tinder, it didn’t work. In Sweden it’s horrible there’s only like four people.” Hence the $180,000 nightclub bills.

“I’m a little bit making up for lost time when I was just programming through my twenties,” he says. “Partying is not a sane way to spend money, but it’s fun. When we were young we did not have a lot of money at all, so I thought, if I ever get rich I’m not going to become one of those boring rich people that doesn’t spend money.”

Right now he’s spending on the permanent office for his new company—a teenage boy’s fantasy that will include a full-service bar, a DJ booth (he’s learning how to spin) and secret rooms hidden by bookshelves—despite the fact that Rubberbrain is nothing more than a name waiting for an idea.

Little inspiration seems imminent. Persson spends a great deal of his time in the current office refreshing Twitter and Reddit, while Porsér checks the fan forums of his boyhood ice hockey team and plays an inane online clicking game that explodes bugs and critters for coins.

“It’s like a day care for us—grown-up day care,” says Persson. Every time a concept comes up, “we try for a couple days and we go back to playing games”.

Perhaps this will pass. But there are also a slew of younger Markus Perssons who are hungrier and more attuned to what the next generation of kids wants. Asked about this, the Minecraft creator responds that he’s completely comfortable being a one-hit wonder. Being insanely rich and prematurely washed up apparently trumps the stresses of responsibility over a virtual nation that alternately reveres and despises you.

“People were starting to talk about the concept of Notch, or whatever, like the ideal,” he says, parsing through his two identities. “I thought back to when I met my idols and [realised], ‘Oh s--t, these are real people…’ That disconnect became so clear to me. I don’t have the relationship that I thought I did with my fans.”

Leaving the Rubberbrain offices, Persson’s assistant hands him a handwritten note from a fan in the US. Written in the looping, practice-makes-perfect cursive of a fourth or fifth grader and pinned together with a single dollar bill, the letter asks Persson to add new features to Minecraft for the young writer. “We got a bribe today,” Persson jokes, before he glances over the note and furrows his brow.

He then points to the dollar. “Should we send it back?”

First Published: Apr 10, 2015, 06:28

Subscribe Now