Why India's Corporate Bigwigs Want to be Bankers

From Tata, Birla and Ambani to ambitious financial services entrepreneurs, everyone sees money in a banking licence. But cut to the core, and what you find is a clear play on the India growth story, a

From Tata, Birla and Ambani to ambitious financial services entrepreneurs, everyone sees money in a banking licence. But cut to the core, and what you find is a clear play on the India growth story, and not much else.

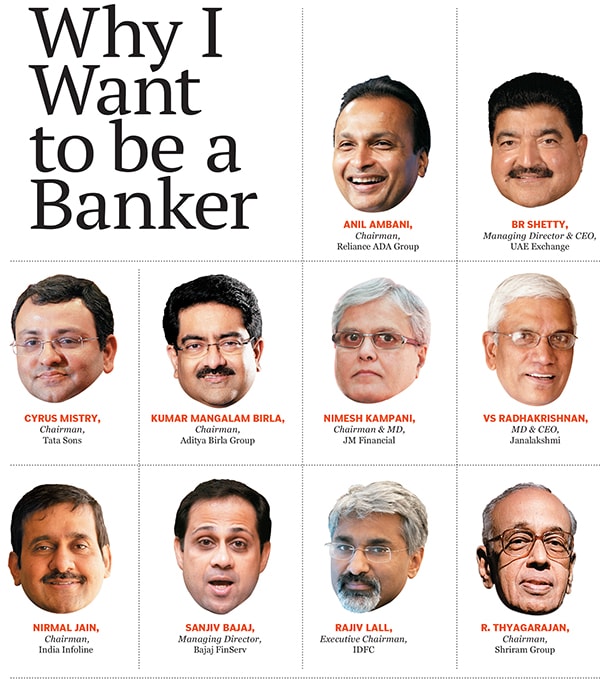

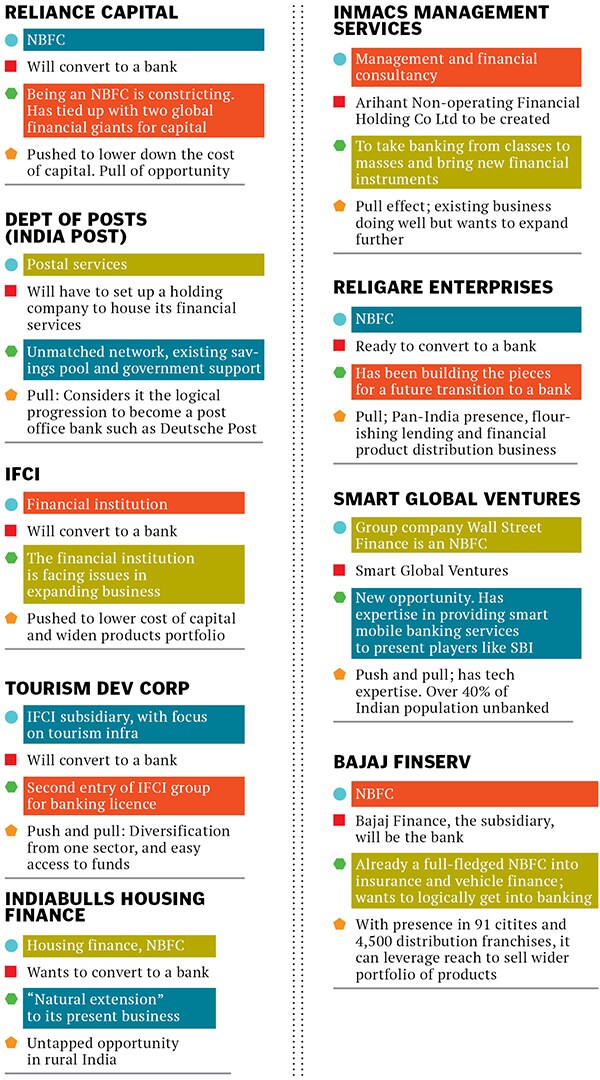

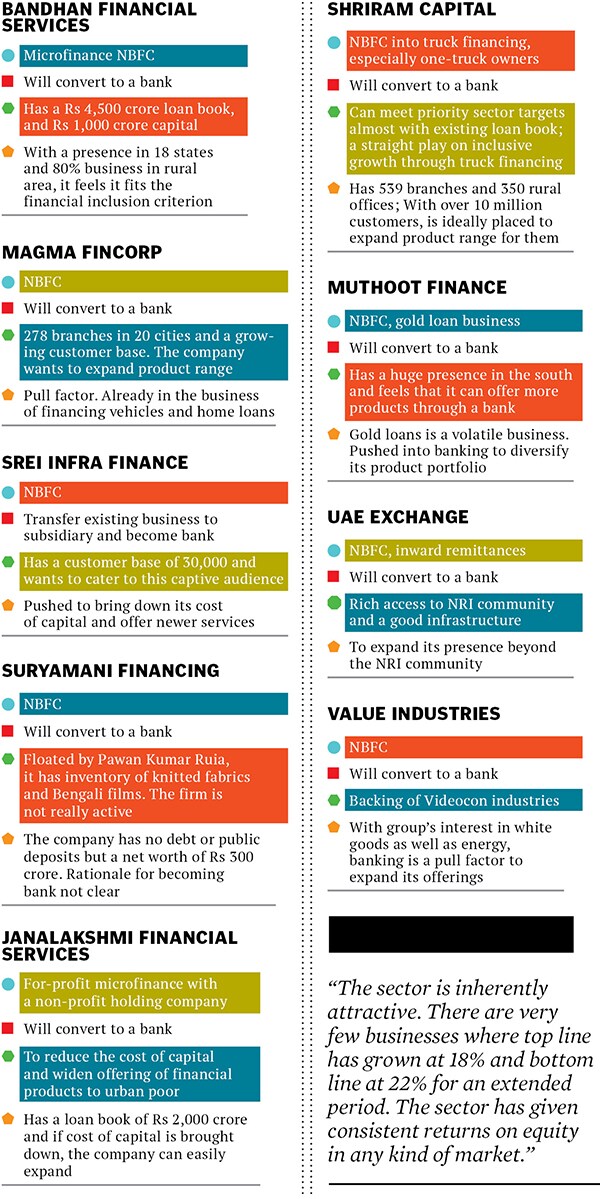

Everyone, from the mighty whales to the financial minnows of India Inc, would like to be a banker. Whether it is the pull effect of a new opportunity that beckons, or the push effect of an existing business model that is going nowhere, or a mix of both, India is awash with entrepreneurs who seem to think that a banking licence is a licence to print money. On June 30, when the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) officially closed its window for applicants, there were 26 in the queue, including the government’s own India Post.

Serving as a beacon for all comers is one outlier: HDFC Bank. On July 17, HDFC Bank reported a 30 percent growth in net profits for the April-June quarter. Nothing odd, it would seem, till you note that it is the 55th consecutive quarter in which it has managed to show that kind of growth. No bank, private or public, has ever managed to equal that feat. Given the consistency of its profit numbers, market analysts have given the bank one of the highest stock market valuations in the world—currently at over five times book value (as on July 15). Its return on assets for 2013-14 is estimated by Espirito Santo Securities (ESS) at 1.87 percent. Put differently, nearly Rs 2 out of every Rs 100 lent by the bank is profit.

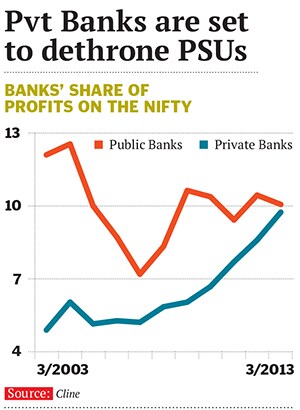

If HDFC Bank is the beacon that tells every aspirant that there’s money in them thar banks, the story is not restricted to one bank. As a group, the major private sector banks have been reporting significantly higher returns on assets (ranging from 1.5 percent to 1.87 percent of assets, against less than 1 percent by and large for public sector banks) and forward price-earnings multiples that are twice or thrice as high as that of public sector banks.

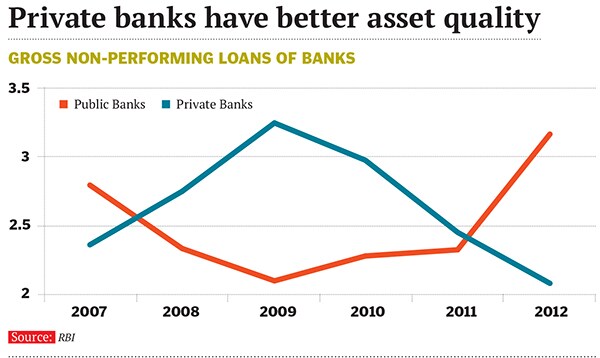

The secret of HDFC Bank’s success, as executive director Paresh Sukhthankar told Forbes India, is that the bank has focussed on balancing three critical variables: Growth, margins and asset quality. “The bank has consciously opted to grow in a manner which balances its growth with stable margins and acceptable asset quality.” Regardless of whether the interest rate cycle is up or down, HDFC Bank’s net interest margins are stable.

In short, if you’re smart, banking is among the best businesses to be in. There’s an outlier to target, and there’s the sloppy public sector to snatch business away from.

The paradox this time around is this: Banking appears to be both the best and worst business to be in. The world over, banks have had a few rough years after the 2008 Lehman bust. In the US and Europe, public trust in them has dwindled, while in emerging economies, including India, the slowdown has impacted profits. The sticky loans of Indian banks have been rising as even big businesses struggle to remain standing in an economy that seems to have entered a period of stagflation.

And yet, market opportunities have increased, quality banking is still lacking in many areas and expansion and proliferation is not well laid out, according to H Srikrishnan, who helped set up HDFC Bank in the mid-nineties and Yes Bank a decade later. “The trick for the new players will be to identify and fill the gaps in the market with innovative products,” says Srikrishnan, who has now joined the board of Religare Enterprises, one of the new aspirants.“The sector is inherently attractive. There are very few businesses where top line has grown at 18 percent and bottom line at 22 percent for an extended period,” says the spokesperson for one of the big corporate hopefuls.

But will the entry of new players change the nature of returns? One of the best ways to look at this sector is by comparing the earnings yield on the NSE banking index with 10-year government bond yields. Banking is one of the few sectors where the earnings yield (which can also be called the yield on equity) has been higher than bond yields for more than 52 percent of the time, indicating that the sector was a buy for much of the past 10 years. But things are changing now. The Bank Index’s earnings yield is now slightly lower at 7.22 percent than bond yields at 7.32 percent.

It’s possible the new banking hopefuls are looking more at the promise of the sector than the immediate profitability. Apart from the usual suspects—Tata, Birla and Ambani—the surprise names in the list of hopefuls were a whole host of players from broking, microfinance, non-bank finance companies, money remitters and infrastructure lenders, among others. Past experience suggests that few make the final cut. Fewer survive.

Of the nine players given banking licences in 1993-94 and two more in the early 2000s, four are gone: Global Trust Bank failed and three others, Centurion Bank, Bank of Punjab, and Timesbank got digested when they gave up the fight for scale in the business. The last three were swallowed, one chomp at a time, by—who else—HDFC Bank. Only two banks—Kotak Mahindra, which converted from an NBFC, and Yes Bank, floated by professional bankers—were allowed in the next round in the mid-2000s. Both have found lucrative niches and are flourishing.

The official reason why the RBI opened a cautious window to give wannabe bankers a chance to try their hand at this craft is to bring a large section of hitherto unbanked and under-banked population into the folds of the organised financial system. For the first time, it is also going to allow big industrial houses to come in. History suggests that private players can never be serious about inclusion unless there is money to be made. The burden of inclusion is largely that of the politically-driven public sector.

In 1969, when Indian banks were first nationalised, there were just 6,900 bank branches in the entire country.

Nationalisation was a determined political quest for inclusion and the government enforced branch expansion, writes journalist Shankkar Aiyar in his 2012 book Accidental India. In 10 years, the number of branches increased to 57,699 as banks were forced to open four new branches in unbanked areas for every branch they wanted in an already-covered area. The number of village branches shot up from 1,833 to 33,014.

Between 1991, the year of liberalisation, and 2011, the banking system, with nearly 1,800 banks, including co-operative banks, added only 30,000 branches, less than a thousand of them in rural areas. That the private sector cannot be lured into serving the inclusion agenda without sufficient profits is clear from the immediate post-Independence as well as recent history.

Aiyar writes that at the end of March 1966, banks (which were mostly owned by big businesses) had lent only Rs 90 crore to the small scale sector as against Rs 1,300 crore to big companies and Rs 500 crore to trade. They had collectively lent only Rs 5 crore to agriculture. Corporate governance was even worse. The 188 people who served as directors in 20 leading banks held 1,452 directorships of other firms besides controlling 1,100 companies.

The trend is no different today. RBI data show that despite the regulator’s insistence on lending to priority sectors such as agriculture, weaker sections and small businesses, most banks do not meet targets. When they do, most follow the letter and not the spirit of the regulation. For instance, only a quarter of farm credit actually reaches small farmers. The rest is given to allied segments or companies dabbling in the industry, lending to whom can technically pass off as priority loans.

In its August 2011 discussion paper on new bank licences, the central bank says: “The experience of the RBI over the past 17 years has been that banks promoted by individuals, though banking professionals, either failed or merged with other banks or had muted growth.”

The experience has not been much different with local area banks and urban co-operative banks. They all suffered from inadequacies of scale, capital and governance, forcing the regulator to shut down some and restrict the functioning of others.

That is why this time, when it was drafting the new rules, it kept the capital threshold high (at Rs 500 crore), insisted on robust governance structures and wants to make sure that eventually all of them are widely held—all good practices followed by many other countries.

Most countries insist on well distributed ownership, some discourage industrial houses and almost all major nations require adequate capital. In the US and Australia, the capital requirement to start a bank is fixed on each applicant’s business plan, while in Singapore you need capital in excess of Rs 5,300 crore, the highest in the world. In Malaysia, the minimum requirement is in excess of Rs 3,000 crore and in Indonesia it is over Rs 1,600 crore. In comparison, the RBI’s base capital threshold appears generous. But there are other norms that increase the regulatory risk.

Among other things, new banks must open 25 percent of their branches in unbanked centres, and they must lend 40 percent of their advances to the priority sector (agriculture, small businesses, exports, et al). They also need to maintain cash reserve ratio and statutory liquidity ratio (CRR and SLR) from day one—even if they already have a huge loanbook. CRR/SLR eats up 27 percent of banks’ deposits right now. For NBFCs that want to convert to banks, it means setting aside a good amount of money for their existing borrowing in the form of debentures or loans because they will fall under what is known in banking parlance as time liabilities.

A senior bureaucrat associated with financial policy in the Central government says if so many applicants have come forward despite the tough conditions laid down by the RBI, it means there is still space for viable business. “Those who have applied [like the Tatas and Birlas] are not dumb, are they?” he asks.

While one does not ask the Tatas and Birlas why they want to be in any business—they are big enough to want a piece of every action—at least one, the Mahindra Group, which also runs a finance company and was expected to apply, did not do so, citing doubtful viability given the tough rules.

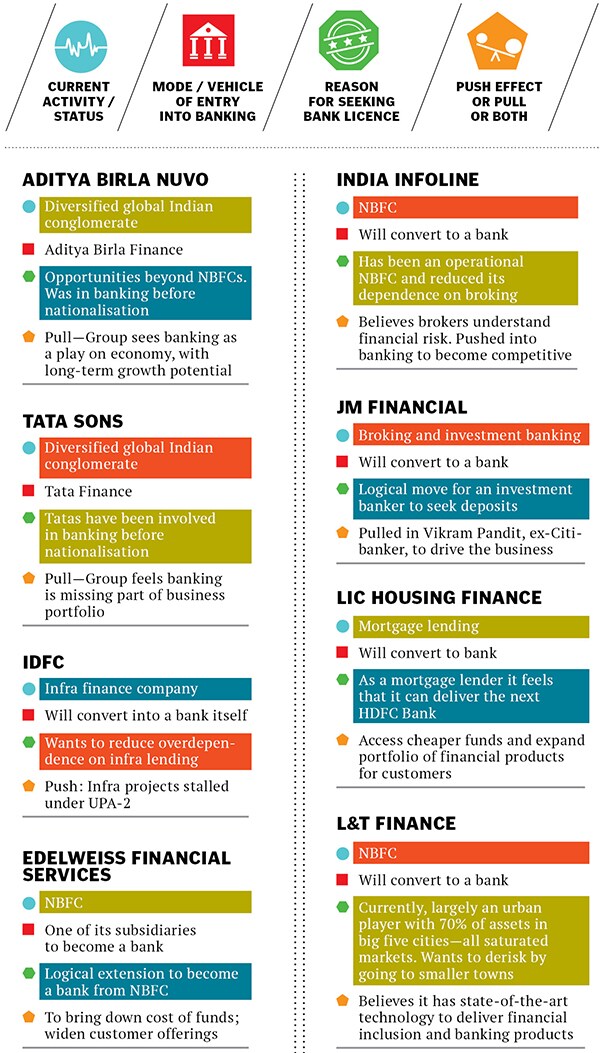

There are four broad buckets in which we can categorise the new hopefuls.

The first bucket is that of the big corporates, who are in it just for the business potential of banking. Among them are the Tatas, Birlas, Ambanis and Larsen & Toubro. Their calculation is simple: If the economy will grow at 7-8 percent over the next 10 years, banking will grow at 15-20 percent annually. That kind of top line growth is enticing.

The second bucket comprises players who are in a focussed line of business and want access to one of the following: Cheaper funds, or a more diversified portfolio of assets. In this bucket one would put LIC Housing Finance, IDFC, IFCI and Tourism Finance Corporation of India. LIC Housing wants to access cheaper public deposits and expand its product offering IDFC wants to get out of the straitjacket of infrastructure lending, as this sector is vulnerable to policy setbacks IFCI and Tourism Finance are parent and offspring, and thus want to balance their deadbeat development finance brief.

The third bucket is the largest—and comprises private sector non-bank financial companies. The RBI treats NBFCs as step-children, and frequently makes rules that work against their core business interests. Example: The curbs put on lending against gold ornaments. These NBFCs now feel that becoming a bank is their best bet for growth.

The last bucket is a category of one: India Post. The government’s postal service finds that it has one of the largest branch networks in the world (over 1.55 lakh post offices, a huge workforce of nearly 5 lakh employees) but not much business to justify the real estate. If India Post were to become a bank, it would have more branches than the rest of the banking system put together—assuming each post office becomes a sort of mini bank.

India Post’s USP would be inclusive banking, but then almost all the aspirants for a banking licence swear by inclusive banking. To be sure, there is some commercial logic to it. According to Espirito Santo research, the metro and urban markets are practically saturated, with the entire population of 377 million more or less covered by 348 million banking accounts. The opportunity is really in the rural and semi-urban areas, where the gap between banking accounts and population is large—344 million accounts to a population of 833 million.

Another corporate spokesman whose group was keen on a banking licence, in fact, pointed out that wealth is no longer a metro phenomenon. “Rural is not what you think it was in the past. With rising MSPs [minimum support prices for food] and high land prices, there is a growing well-off customer base to be serviced in rural areas.”

Little wonder, most of the new entrants think this is where the moolah is. BR Shetty, chairman of UAE Exchange, which handles millions of dollars in remittances from the Gulf, says despite the fast growth of banking in India, “there are several unmet customer needs” at the bottom of the pile. He thinks UAE Exchange is uniquely placed to cater to this segment.“Our experience is in working closely with the bottom of the economic pyramid, which sends money in the range of Rs 15,000 to Rs 18,000. Working with this segment of customers and bringing them into the formal financial system is our biggest strength.”

In contrast, microfinance lender Janalakshmi Financial is clear that there is enough bottom-of-the-pyramid business in the urban areas too. Janalakshmi wants to do more than just lend to the non-prime borrower.

VS Radhakrishnan, managing director and CEO, says his logic for becoming a bank is to move beyond lending and “serve our target customers with a full product range. Our customer research shows that these customers need a much broader array of financial products than just the credit products that we offer today. Most critically, they need savings and payment products, which we cannot offer with our current model.”

Janalakshmi’s microfinance business is for profit, but the parent company, Janalakshmi Social Services, started by ex-Citibanker Ramesh Ramanathan, is a non-profit.

For big business groups which already cater to the rural market by supplying either agricultural inputs such as fertiliser and pesticides, or goods such as steel and cement, or even motorcycles and mobile telephony services, the attraction of having a bank to serve and fund all is immense. They are already present, and it’s about tapping a customer they already know.

Inclusion, though, is not always about building unviable branches in villages. BK Modi’s Spice Global is one group which plans to make technology its USP in banking. Says Preeti Malhotra, Group Executive Director at Spice Global, whose banking application has been made in the name of Smart Global: “Technology will be the differentiator for us and we will focus on smart mobile banking. It is the most cost-effective solution. The cost of one physical transaction is Rs 40-60 and through a mobile it is Rs 1-1.5. An ATM transaction costs Rs 15-20. Of our six lakh villages, only 5 percent are covered by commercial bank branches 46 percent of the population is still unbanked. At the same time, almost everyone has mobile phones. They access the internet through the mobile phone.”

But then technology is a commodity. What one banker can access, everyone else can. H Srikrishnan, a board member of Religare Enterprises, says that basic services—ATMs, online banking, etc—are a given today. He believes that there are growth areas available in sectors such as agriculture (not necessarily farmers, but in allied segments such as traders, middlemen, farm infrastructure providers, etc). The new players will have to offer high-end products and services at a low cost. “Service is the key but not the door to success any more.”

The bottleneck, some believe, will be in getting the right kind of bankers on board—even before getting a licence. The Religare Group of the Singh brothers (Malvinder and Shivinder) has thus begun tanking up on talent. Apart from Srikrishnan, it has roped in former Canara Bank Chairman AC Mahajan and former finance secretary Arun Ramanathan.

In Religare’s case, as in many other cases, one plan is to morph the group’s existing non-bank finance company, Religare Finvest, into a bank. As part of the preparations it has tied up with Philadelphia (US)-based Customers Bank—a small five-branch bank which recently expanded its network to 19—as a strategic partner. The tie-up has more to do with the learnings of the founder of the bank than the bank itself. Customers Bank is focussed on the SME segment, which is also a target for Religare, says Srikrishnan.

Religare Finvest, which is the lending vertical of the Singhs’ non-operative holding company Religare Enterprises (REL), has a book size of around Rs 14,000 crore. It accounts for 60 percent of REL’s total revenues, and broking accounts for only 10 percent.

In most cases, it seems, the idea is to convert the existing NBFC into a bank. The Aditya Birla Group, for example, will use its relatively small Rs 8,000 crore balance sheet of Aditya Birla Finance to convert it into a bank. The Tatas, though applying through Tata Sons, will do the same with Tata Finance, which has a much larger book.

Indiabulls, which has a lending book worth Rs 35,000 crore, sees banking as a logical extension of its finance business, says Ajit Mittal, executive director of the group. “We are among the biggest in housing loans, and are also present in the commercial vehicle and SME segments. We see ourselves as a financial services conglomerate.” With Rs 7,000 crore of surplus cash, Mittal sees no hiccup in meeting CRR/SLR requirements from day one if given a licence.The most difficult job will probably be that of Infrastructure Development and Finance Company (IDFC), which will be seeking to migrate a Rs 71,000 crore balance sheet into a bank—which means thinner margins for several years going forward, as capital gets blocked in maintaining CRR and SLR balances.

According to Edelweiss Capital, IDFC carries less than 10 percent of its net demand and time liabilities as SLR securities, which will have to be raised to 27 percent (CRR plus SLR) in one go if it gets a banking licence. This means huge capital-raising plans in the future. Since IDFC will also have to meet priority sector lending targets (40 percent of advances), it will face a huge strain on resources. Quite clearly, it is feeling the push effect from being a mere infrastructure lender at a time when policy paralysis in UPA-2 has stalled most infrastructure projects. It wants to move to the safer shores of commercial banking, never mind the medium-term pain.

According to Edelweiss, which itself has applied for a banking licence, NBFCs seeking to convert to a bank will see a halving of return on equity (RoE) in the initial years due to the regulatory drag caused by CRR/SLR and priority sector lending. “It will take at least four to six years to ramp up to average lifecycle RoEs ,” it says.

About its own plans, Edelweiss has this to say: “The proposed Edelweiss Bank will have about 75 branches by the end of the third year of operations, 21 of them in rural locations. This will give it access to deposits of Rs 10,000 crore and advances of Rs 9,600 crore. By year six, we should have 242 branches, a deposit base of Rs 36,000 crore and advances of over Rs 29,000 crore.”

Nirmal Jain, Chairman of India Infoline, says his strategy is to go where others are not so keen. “We will be different from existing banks in terms of our focus. Our focus will be on micro, small and medium enterprises and financial inclusion. We shall not be focusing on wholesale banking or corporate banking which is bread and butter for most of the existing banks.”

But here’s the rub. Everybody says he is different, but everybody’s strategy is more or less the same: focus away from the big metros, use technology to lower costs, expand the range of products on offer to existing customers, and so on.

So why do they all think they are in with a chance? Jain’s answer: “Our strategy of growth and profit is to leverage India’s growing economy. India’s economy, in monetary terms, is expected to grow 15 percent per annum.”

The banking industry’s close linkage to the economy has ensured around 18 percent RoE, and sometimes even more. “It is a sector that has given consistent returns on equity in any kind of market. There are other sectors like FMCG or two-wheelers which have delivered higher RoEs, but what is interesting is the way banks price their risk in any kind of market”, says Prabodh Agrawal, head of research at IIFL, institutional broking.

It’s clear what the new hopefuls are betting on: The India growth story. Nothing else. And yes, the fat profits of HDFC Bank continue to be rivetting.

(Additional reporting by Prince Mathews Thomas, NS Ramnath and Vivek Kaul)

First Published: Aug 05, 2013, 06:04

Subscribe Now