Prerna Chandak, 22, a medical student who lives with her parents in Nagpur, orders in food about three times a week. She studies until late, and usually has dessert delivered to keep her fuelled through the night. About two weeks ago, she switched loyalties from Swiggy to Uber Eats, “because Swiggy doesn’t let you apply discounts after you place the order. It makes a huge difference,” she says. Roughly, each order she places is discounted by about 30 percent.

Chandak is also on Zomato Gold (ZG), a dine-in programme now mired in controversy. ZG gives its members ‘1+1’ offers on food at certain restaurants, ‘2+2’ on drinks at others.

Twenty-one-year-old engineering student Abdul Rehman, also a member, says he’s saved ₹20,000 in 10 months with ZG. He uses it three to four times a week, and orders food on delivery multiple times a week. “For a restaurant junkie like me, saving about ₹2,000 a month is a big deal,” he says. “If Gold is discontinued, I would think twice before going out every few days.”

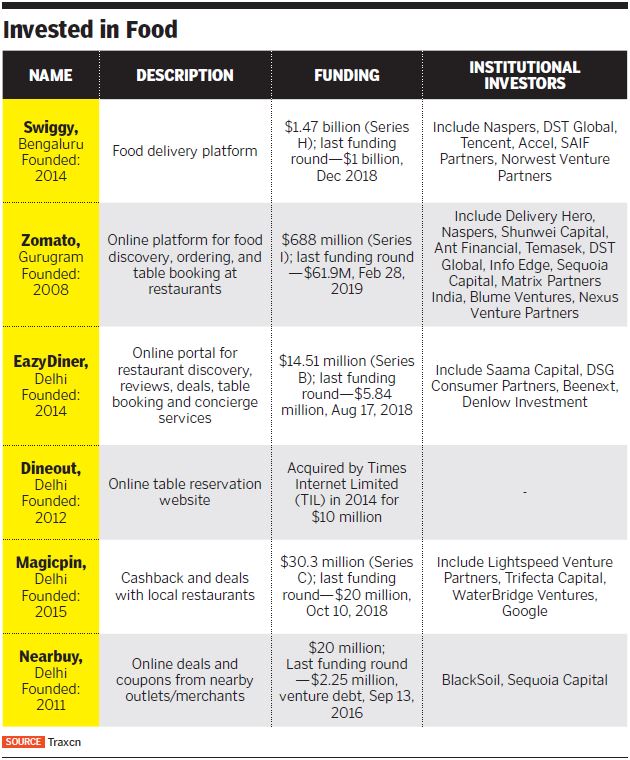

As competition between food tech players gets stiffer by the day, the customer acquisition playbook is bringing out a quick fix: Let them eat cake, for free. With pockets that are deepened with investor money (see box), food tech aggregators are burning cash to cut themselves a slice of the booming market, luring customers with the biggest discounts they can offer. The customer is slowly becoming more agnostic and, like Chandak, switching over to the aggregator that leaves them with the most money in their virtual piggy bank. Discounts can run as high as 60 percent.

![g_120195_g4_280x210.jpg g_120195_g4_280x210.jpg]()

This is part of a seeding phase, to get more and more people into the habit of using food tech every day. However, a likely casualty in this equation is the restaurant, which often ends up footing the deep discount from its own pocket, which doesn’t run quite as deep as that of the aggregator. So on August 14, the National Restaurant Association of India (NRAI) launched a nationwide protest against deep discounting. A #Logout campaign urged restaurants to opt out of dine-in discount programmes and aggregators such as Zomato Gold, EazyDiner, Dineout, Magicpin and Nearbuy, claiming they were hurting businesses with ‘unjust practices’. Overnight, 300 restaurants had joined the protest at the time of going to press, more than 2,000 had ‘logged out’ across the country, including some of the country’s leading F&B brands—the Olive Group, Indigo Deli, Social, and others.

Nearbuy offered discount coupons for various restaurants, while Noida-based table reservation platform Dineout’s membership programme called Gourmet Passport gave subscribers a ‘buy-one-get-one’ on buffet, food and drinks at more than 1,500 restaurants across the country. The #Logout campaign was also supported by the Federation of Hotel & Restaurant Associations of India (FHRAI), who, in a letter to the aggregators, called for a review of their schemes and requested them to engage in a fruitful dialogue.

“Dineout has never imposed any discount conditions on our partner restaurants,” Dineout co-founder and CEO Ankit Mehrotra tells Forbes India via email. “Even right now, restaurants have switched off the discounts on our platform, but are accepting reservations from us. Our only request to NRAI is to clarify the stand on discounts and to make it uniform for all aggregators. The main challenge is with deep discounts, which we already do not partake in.”

At its peak, ZG had 12,000 partner restaurants on board across the world, of which 6,500 are in India. As of March 31, 2019, it had more than 1.4 million active subscribers globally—compared to just 170,000 in March 2018, as per a blog post on its website. This is part of the problem. When it began, ZG was meant to be an exclusive, ‘invite-only’ programme, and sold to partner restaurants as such. ZG discounts would be available to the chosen few, numbering about 10,000. However, that number soon touched 20,000 after a point, ZG was available for anyone to purchase (for a slightly higher price, at about ₹1,800, up from about ₹1,200).

![g_120205_food_aggregator_280x210.jpg g_120205_food_aggregator_280x210.jpg]()

“These apps will keep popping up with coupons worth 40 or 50 percent, or giving you 1+1 or 2+2,” says Rahul Singh, founder of The Beer Café and president, NRAI. “The bottom line is, customers never asked for these discounts. If you book a hotel through Airbnb or Booking.com, you pay a small transaction fee. But here, it’s a grand theft, because while an aggregator will promise you the discount, it is the restaurant that is losing that money.”

For instance, Singh explains, if Zomato charges members about ₹1,000 for a Gold subscription, and claims to have a million subscribers, that is about ₹100 crore. Moreover, they charge restaurants a fee upwards of ₹40,000 to sign up as a Gold partner, claiming to bring them more traffic and more transactions. “That’s a lot of money,” he adds. “So naturally, the customer assumes that Zomato is subsidising costs, but that’s not the case. A restaurant is burning a large amount of money for Zomato to offer this programme. So if people say we are fools to have signed up for this, they are right. Yes, we are fools who got into this trap. But it is time to set this right.”

For users such as Chintan Joshi, 30, a cyber security consultant who orders in food five times a week and uses ZG only once a month, the convenience matters more than the discount. “My choice of restaurant does not depend on Gold. That’s just an added benefit. Honestly, I use these platforms for the convenience of getting food more easily. Prices and discounts do not really matter that much.”

ZG announced an addition to its business in July, the Zomato Infinity Dining programme, which allowed Gold members all-you-can-eat access, along with an open bar at partner restaurants, at a fixed per-person price. More than 350 restaurants had apparently signed up to be on it. Rumours were rife that ZG would be extended to food delivery, and restaurants were worried they would be losing more and more money.

“There were no fundamental marketing principles at play here,” says Munaf Kapadia, founder of The Bohri Kitchen and member of the NRAI. “The basics say that when you want to acquire a new customer, you offer a discount, and once you have that customer, you rub off the discount, so your customer lifetime value grows. But none of that applies here. Everyone gets a discount, and continues to do so.”The aggregator, he adds, has become the shepherd, and restaurants become the sheep, for fear of losing out. “So Zomato first went out and got 50 restaurants on board that thought they were part of an elite, niche club. Soon, that club became 1,000 restaurants, then 10,000—and before we knew it, there were billboards asking people to join ZG,” he says. “It turned into a behavioural pattern in the ecosystem.”

![g_120207_top_food_request_280x210.jpg g_120207_top_food_request_280x210.jpg]()

After a few days of tussle, the NRAI managed to put together meetings with the food tech aggregators mentioned above at the end of two days, it was suggested that discounts should be capped at about 15 percent. Last fortnight, Zomato founder and CEO Deepinder Goyal had written to restaurants with a modified Zomato Gold programme. According to the letter, which Forbes India had access to, effective September 15, trial packs for Gold would be discontinued, customers abusing the privileges would be removed, and users would be allowed to unlock the Gold offers only once a day, and use only two Gold accounts per table. However, restaurants hit back, saying it was ‘old wine in a new bottle’. “It’s a tweak in the drug that doesn’t solve the addiction,” says Singh of NRAI. “We don’t have a tech aversion but our fight is against deep discounting, which undervalues the restaurant experience and its offerings.”In an interview days before the #Logout campaign, Zomato co-founder and COO Gaurav Gupta told Forbes India, “Our take on discounting is different. When we talk about discounts, we should say what is the best price we can offer that ensures that restaurants also make good margins. It should be a fine balance, and whether you call it the right price or discount, that’s the thing. Zomato is looking to shape the ecosystem in both eating out and at home.”

The same principle the NRAI is fighting when it comes to dine-out discounts, say restauranteurs, also applies to food delivery, where similar offers are doled out by the likes of Zomato, Swiggy and Uber Eats. “You have these guys with crazy funding, amazing creativity and innovation and energy, and the best marketing innovation they can come up with is a 50 percent off? It blows the mind. Why haven’t they come up with innovative ways to generate additional business that is beyond a big discount? It’s incredible short-sightedness,” adds Kapadia.

“Discounts are lucrative,” agrees Swiggy COO Vivek Sunder. “That’s true for any industry. But while we believe there’s a role for discounting, our business doesn’t need to run on it. I want to emphasise that we discount far less than our competitors, as a consumer’s choice depends on all kinds of environmental factors.”

![g_120193_g3_280x210.jpg g_120193_g3_280x210.jpg]()

For example, he says, if a Mumbai-based customer wants a burger from Salt Water Café, he is unlikely to care if there isn’t a discount on it. “In fact, in the past few months, only 30 percent of our orders are from people who have applied the discount coupon—either because relevant discounts are not available, or because they just want a specific kind of food. There is a genuine need that is not artificially created.”

The other issue restaurants have with delivery services is the bundling of discoverability with delivery. This means that if your restaurant does not use the platform’s delivery services, it is unlikely to be visible in search results. Yet another is data masking.

“We need to find ways for everyone to coexist,” says Riyaaz Amlani, CEO, Impresario Entertainment and Hospitality that owns restaurants like Social and Smoke House Deli. “Restaurants need visibility and traffic, so you could keep time-bound discovery mechanisms.”

For instance, Dineout has a ‘Great Indian Restaurant Festival’, where for a certain period, customers can go to a quality restaurant they could otherwise not afford. “And hopefully, you will like it enough to come back. Here, the restaurant can build its own relationship with the customer,” adds Amlani. “But in delivery, data is masked by aggregators such that I cannot see who my customer is. How can I build a relationship with them? They are controlling the funnel and the pipeline, and will leverage that in ways that will suit only them.”

Kapadia, a former Googler, explains with an analogy. Google search has become an index for the internet, and when you become that gateway, the power yields you the responsibility to take care of your stakeholders. “Today, to some extent, you can feel like Google is neutral to its stakeholders, mainly because of Google Analytics, which gives you transparent data on how many people are visiting your website, and how they got there,” he adds. “There’s an entire industry built on search engine optimisation that leverages this. However, these players attempt to be similar gateways to everything food-related on the internet, but to date, I have no idea what affects my Zomato rating.”

For instance, he says a friend of his with a health food startup has 99 5/5 ratings, and one 2/5 rating, and his average rating on Zomato is 3.5. “I understand that it’s a weighted average, but even then it doesn’t make sense,” he says. “By now, Zomato should have released an in-depth study explaining exactly how it works, so people have no doubt.”

Aggregators say it’s an operational challenge too. “We have 120,000 restaurants, and we don’t have the corresponding manpower, so instead of individual transaction data, we give restaurants data insights on the app that could help them improve business,” says Sunder of Swiggy. “We don’t want to be in a situation where personally identifiable data of customers—name, phone number, etc—is available to our salesforce or to our thousands of restaurants,” he adds. “No customer would want that.”

Such data, however, is shared with ‘sophisticated players who have great data protection systems in place’. One such example is Jubilant [which runs Domino’s in India]. “There’s some merit to be had in sharing transaction-level data while protecting customer identity with such players,” Sunder adds. “The answer then is absolutely yes—data sharing there leads to a win-win.”

Silver Lining

Swiggy is also betting on a new food tech trend for the long term, a space that has a clutch of key players already—cloud kitchens and dark kitchens. A ‘ghost kitchen’ or dark kitchen is one that is not visible to its customer it offers no dine-in or takeaway facility, but runs entirely on delivery. A cloud kitchen is one that operates more than one food brand from its dark kitchens.

India’s largest player in this space is the Pune-headquartered Rebel Foods, which operates brands such as Faasos, Behrouz Biriyani, Oven Story and Mandarin Oak. It has raised $302 million in funding, the latest being a $125 million Series D round, in August. Its key investors include Coatue, Goldman Sachs Investment Partners, Gojek, Lightbox Ventures and Sequoia Capital. FreshMenu, based in Bengaluru and founded by Rashmi Daga, has raised $24.5 million in funding, and operates about 40 cloud kitchens in Bengaluru, Delhi and Mumbai. Rebel Foods has about 235 in 15 cities. FreshMenu claims to have become profitable from August onwards.

Cloud kitchens can save on prime real estate costs, since they do not have to be customer-facing. Moreover, with low operating costs, they can be agile and tailor the menu to the latest food fads, while using data to see which items sell the most.

For instance, FreshMenu, which started with non-native Western cuisines, now has a range called ‘Fit & Fab’, including meals for the carb-conscious—a category that accounts for almost 20 percent of its business today. When Faasos wanted to introduce biryani, which is the single most ordered dish across the country, the wraps and rolls brand realised nobody was ordering it. “Faasos was strongly associated with wraps, just as Starbucks is with coffee,” says Jaydeep Barman, co-founder and CEO, Rebel Foods. “So we launched it under a new brand, Behrouz Biryani, and it took off. Behrouz is India’s largest consumer of mutton after the Indian Army—it’s that crazy. That was a lightbulb moment for us, and we began creating more such cuisine-driven national brands. Now, we have 10 brands.”

Rebel Foods is scouting for locations in Indonesia, and is launching three kitchens in Dubai. It plans to have 20 kitchens in Dubai by the end of the year.

"The funds we have raised will be focussed on three aspects—expansion of our kitchen footprint from 235 to 300 investments in artificial intelligence (AI)-driven personalisation as well as kitchen automation and robotics and building and scaling interesting brands,” adds Barman. “Not only are all our kitchens profitable, but we also recover our kitchen capex in seven to eight months, compared to a typical brick-and-mortar restaurant’s capex payback of five years.”

FreshMenu is banking on the health trend, and of delivering freshly cooked food. “Our business model is that there will be neighbourhood kitchens cooking fresh food, not delivering food in frozen packets across the city,” says Daga. “So this was a deviation from the QSR model of service. Fresh food will always taste better, and therefore, we have high customer retention. The use case will only increase—you cook less often than your parents, and your children will cook less often than you. Fresh food will have to come from outside.”

Aggregators such as Swiggy have also entered the cloud kitchen space Swiggy has its own private labels, but also leases out kitchen space to food brands under Swiggy Access. However, it will not pit a rival against a strong cuisine player in a particular area, as there will be no need for it there.![g_120671_drone-232490590_1_280x210.jpg g_120671_drone-232490590_1_280x210.jpg]() Uber Eats has started to pilot drone delivery in San DiegoImage: Shutterstock[br]The Future

Uber Eats has started to pilot drone delivery in San DiegoImage: Shutterstock[br]The Future

What will the food tech landscape look like five years from now? As with any technology business, the rapid adoption of AI and machine learning means that more and more user data will be put to work, and recommendations are likely to become so personalised, say futurists, they might even link directly to your individual genome, so that you’re eating exactly what you need.

Platforms are also likely to become more content-driven, resembling your Instagram feed more and more, getting restaurants to create videos, stories and so on. “We’re building a platform where restaurants could bring engaging stories for their users, that they may not otherwise be able to share,” says Gupta of Zomato. “We’re definitely ramping that up to add more innovations to this vertical.”

Uber Eats is not only working on becoming more content-driven, but also on product developments such that it quickly learns how you operate and can become ingrained into your daily routine. “We want to find ways to integrate the rides experience and the Eats experience,” says Stephen Chau, senior director and global head of product–Uber Eats. “So if you take an Uber to work every morning and order breakfast around the same time, can we integrate the services such that your pre-ordered breakfast is waiting for you in the car?”

Uber Eats has begun to pilot drone delivery in San Diego. “We have no plans to launch that anywhere else yet, but we do think that over time, especially in congested cities in Asia, there is an opportunity to leverage that,” says Raj Beri, head of Uber Eats–APAC. “It will create a magical experience and over time, lead to a sustainable solution.”

“Drone delivery will depend on the business use case,” says Sunder of Swiggy. “But electric delivery is likely to become a reality soon. But being in the technology world means that any prediction you make is likely to be wrong,” he says with a laugh.

For cyber security consultant Chintan Joshi, who orders in food five times a week, convenience matters more than the discountImage: Mexy Xavier [br]

For cyber security consultant Chintan Joshi, who orders in food five times a week, convenience matters more than the discountImage: Mexy Xavier [br]

Uber Eats has started to pilot drone delivery in San DiegoImage: Shutterstock[br]The Future

Uber Eats has started to pilot drone delivery in San DiegoImage: Shutterstock[br]The Future