Food, food, everywhere but not enough to eat

As erratic weather patterns and depleting resources complicate the many factors of food security in India, change is coming, from ground up

Picture: Getty Images[br]The 3.75-acre sugarcane farm of CV Kumar is green. The 55-year-old farmer in the village of Holalu in Karnataka’s Mandya district is all smiles as he talks about how the yield of his land has doubled—from 40 to 45 tonnes per acre to more than 80 tonnes per acre. His input costs have reduced significantly as well, with fertiliser requirements falling by 50 percent, and water by 40 percent. His new-found confidence now enables him to grow paddy on another 2 acres, and a variety of vegetables for subsistence.

Picture: Getty Images[br]The 3.75-acre sugarcane farm of CV Kumar is green. The 55-year-old farmer in the village of Holalu in Karnataka’s Mandya district is all smiles as he talks about how the yield of his land has doubled—from 40 to 45 tonnes per acre to more than 80 tonnes per acre. His input costs have reduced significantly as well, with fertiliser requirements falling by 50 percent, and water by 40 percent. His new-found confidence now enables him to grow paddy on another 2 acres, and a variety of vegetables for subsistence.

The secret to Kumar’s farming success—which has now caught the eye of the government, which is expected to announce policy measures soon—lies buried under a foot of soil on his land: Thousands of metres of plastic pipelines that drip water and water-soluble fertilisers in a controlled and concentrated manner near the roots of his crops. Not only do they help the crops grow better—with the right amount of water and nutrient at the right time—they drastically reduce the amount of water required to grow sugarcane (traditionally grown by flooding the fields) and the amount of fertilisers leaching through the soil and increasing its toxicity.

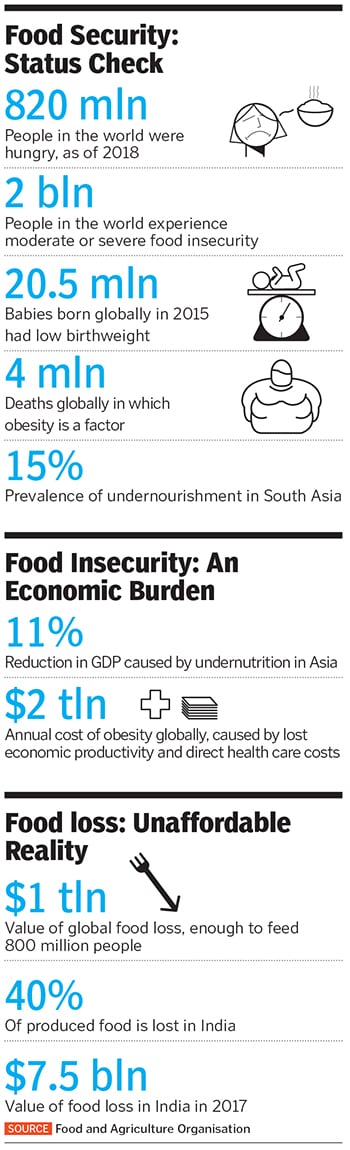

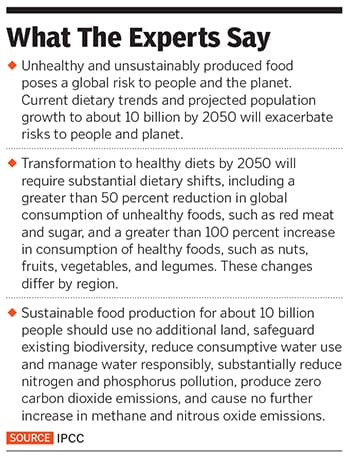

The health of the planet and that of humans have always been inextricably entwined. But never have they faced the strains they now do. For, while, on one hand, food production is sucking up natural resources like never before and is one of the largest contributors to environmental degradation, on the other, it is the pressing need to feed nutritious food to a burgeoning global population, significant portions of which remain underfed and undernourished.

Adding to this equation is the looming presence of climate change, which brings in its wake erratic heat and rain patterns, and extreme weather events such as droughts and flooding. Given India’s growing population—currently at 1.3 billion, it is expected to be the most populous country, ahead of China, by 2027—and the increasing effects of climate change the country has been experiencing, ensuring food security and environmental sustainability are two forces that could be perceived to be pulling in opposing directions.

And yet, ensuring one is the means of ensuring the other.

Food security, as defined by the United Nations’ Committee on World Food Security, means that all people, at all times, have physical, social, and economic access to sufficient, safe, and nutritious food that meets their preferences and dietary needs. It stands on the four pillars of availability, access, utilisation, and stability, which means that production of vast quantities of food alone is not enough. CV Kumar is one of the earliest converts to drip irrigation in Holalu village in Karnataka’s Mandya district. He has 3.75 acres of sugarcane fields covered in pipelines

CV Kumar is one of the earliest converts to drip irrigation in Holalu village in Karnataka’s Mandya district. He has 3.75 acres of sugarcane fields covered in pipelines

Image: Nishal Lama for Forbes India[br]“After the Green Revolution, India has had sufficient production of food,” says RV Bhavani, director, Agriculture Nutrition Health Programme at the MS Swaminathan Research Foundation in Chennai (MSSRF). “The access that people have to food, through distribution systems, has always been a problem.” Leakages in the public distribution system (PDS), for instance, is one of the reasons why food does not reach the people who are most in need of it.

Loss of produce between the farm and consumers—in India the figure stands at an estimated 40 percent—is another major reason why food does not reach end-users. “In our country, we don’t encourage the use of frozen and processed food, and instead prefer fresh food. But it is not possible to transport and distribute all the produced fresh food before it goes bad,” says Vandana Singh, CEO, Food Security Foundation India. “What we need are good storage facilities, means of transportation, and processing plants to reduce wastage at the farm level.”

One of the lasting legacies of the Green Revolution has been the shift away from a diverse variety of crops, and the dominance of food crops such as wheat and rice, and cash crops such as cotton and sugarcane. Consequently, cultivation of indigenous varieties of cereals and grains, such as millets and sorghum, barley and buckwheat has been relegated to the sidelines. Along with issues related to market linkages—these enable farmers to sell their produce, and that produce to be stored, transported and distributed to consumers—shrinking consumer demand has further reduced the farming of these crops.

“Food security includes nutritional security. In this regard we are far from achieving the Sustainable Development Goals that have been set by the UN General Assembly for 2030,” says Bhavani. “Diets in our country are primarily cereal based, which account for basic calories and protein. But there are high levels of micronutrient deficiency. Agricultural policy has focussed on cash crops, not on nutrition. At laboratory research levels also, rice, wheat and cotton remain in focus, not millets and pulses.”

Adding to these existing conditions are the problems being caused by climate change, with rising temperatures, erratic rain patterns, and extreme weather conditions such as droughts and floods. An August 2019 report by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) says rising temperatures will reduce yields and nutrient content of crops, while changing the distribution of pests and diseases.

Another legacy of the Green Revolution has been the indiscriminate use of water and pesticides to grow high-yield varieties (HYV) of crops HYV of wheat produce 40 percent more than traditional varieties, but require 300 percent more water to grow. With many state governments subsidising water and electricity to farmers, the latter has not seen much reason to rationalise their use.“Of the total water usage in our country, 85 to 90 percent is for agricultural purposes. But more competitive uses are now coming up, with sectors such as services, industries and urban areas vying for water,” says Ajith Radhakrishnan, India country coordinator and senior water resources management specialist with 2030 WRG, a World Bank initiative, adding that subsidised urea prices have resulted in its excessive use. This despite the fact that almost 90 percent of it is lost as it leaches through soil, adding to the nitrate toxicity of ground water and rivers.

Radhakrishnan adds that the indiscriminate sinking of borewells by people on their private lands over the last decade has severely depleted ground water levels. According to the 5th Minor Irrigation Census conducted by the Central Ground Water Board, and released this June, the groundwater level in India has declined by 61 percent between 2007 and 2017 of the extracted water, 89 percent is used for irrigation. This depletion has been the most significant in Northwest India.

Along with depletion of ground water, “the prevalent farming practices have led to increased soil salinity in Punjab, which is not sustainable”, says Bhavani of MSSRF. “Dr Swaminathan [known as the ‘Father of the Green Revolution’] had, in fact, warned that excessive use of pesticides and water would affect soil and plant health.”

Focus on crash crops has also reduced household food and nutritional security, with farmers growing only those crops that are expected to bring in money. This has led to a predominance of mono-cropping. “More than 50 percent of the land in the Vidarbha, Jalgaon, Marathwada and Pune regions in Maharashtra is under cotton cultivation. But farmers can’t eat cotton,” says Sangram Salunkhe, regional coordinator (west and south), Action for Food Production (Afpro). “If there is a crop failure, neither do they have cash to buy food, nor do they have food crops that they can eat.”

Multi-cropping and crop diversification is not beneficial just for humans, but also for the crops themselves. Large-scale cultivation of a single crop also makes it highly vulnerable to pests, says Tomio Shichiri, the India representative of Food and Agriculture Organisation, “with diseases turning into epidemics”.

Working towards ensuring the various aspects of food security are organisations at various levels that are cultivating ways to harness the benefits of traditional forms of farming and cropping patterns, as well as technological advancements that reduce the demands on natural resources. Through long-term projects that partner with private and public players, these organisations are raising awareness and knowledge among farmers, enabling the funding of technology adoption, and creating market linkages.

For instance, Afpro has been working in about 500 villages in Maharashtra to raise awareness about proper conservation and utilisation of ground and surface water through the creation of farm bunds (barriers for harvesting surface water), and farm ponds. “We are focusing on crop cultivation and farming systems, to encourage practices such as crop rotation, mixed cropping that includes food crops, and reduction of input costs,” says Salunkhe. The last, he adds, is being achieved by rationalisation of inputs such as water, fertilisers and pesticides.

Earlier, farmers would apply these inputs with little awareness of whether the crops actually need them. “Through frontline demonstrations and training sessions, we have taught them methods to test their soil, so that they know what the level of potash or urea is,” he says. “They apply fertilisers when the levels are low. Similarly, they have learnt how to analyse the levels of pest infestations, and apply pesticides only when necessary. This has brought down input costs by about 40 percent.”The work that is taking place in four districts of Karnataka—Bagalkot, Mandya, Chikmagalur and Gadag—is an example of a multi-stakeholder approach to promoting the adoption of new technology, such as drip irrigation, in the cultivation of crops that includes water-intensive varieties such as sugarcane. After the Karnataka government approached 2030 WRG—an initiative under the World Bank Group that brings together public, private, and civil society stakeholders to improve the management of water resources—memorandums of understanding were signed by 14 private companies, the state’s departments of agriculture, horticulture and water resources, and the state government in 2017.

Laying the drip irrigation pipelines costs between Rs 50,000 and Rs 1.5 lakh per acre (depending on the kind of crop, and soil conditions), on which the Karnataka government gives a 90 percent subsidy. “Operation and management [O&M] charges for the first five years of the project are borne by Jain Irrigation and Netafim, two private companies that were brought in to lay the drip irrigation infrastructure,” says Mandar Nayak, member of 2030 WRG’s Karnataka team. “The farmers have been organised into Water User Associations, which will collect water charges to be used for O&M of the project water pipelines after the five-year period is over.”

The projects cover close to 90,000 hectares and 1.44 lakh farmers, who grow a variety of crops, including Bengal gram, green gram, maize, cotton and pigeon pea. “It is important to demonstrate to farmers the benefits of drip irrigation,” says PV Joshi, a senior agronomist with Jain Irrigation, who works in the Malavalli taluka of Mandya district. “They have had bad experiences before, with government projects being started but not being implemented. So winning their trust is crucial.”

Farmers implementing the drip irrigation systems draw water from existing borewells on their lands, since the water needs to be pumped into the pipelines at a consistent pressure, and this is not possible with water from canals distributing river water. So although the demand for borewell water is halved, it still exists, and continues to deplete an already-stressed water table. To address this issue, Jain Irrigation is now building a system—consisting of an extensive network of pumps and pipelines—that will be able to distribute water from the Cauvery river in a manner that can be used for drip irrigation. The system is expected to be fully operational by early next year. Ramesh Medaiah has already made eight pickings of brinjals from his farm in Mandya and is expecting two more, thanks to drip irrigation, compared to an average of four to five pickings under regular irrigation

Ramesh Medaiah has already made eight pickings of brinjals from his farm in Mandya and is expecting two more, thanks to drip irrigation, compared to an average of four to five pickings under regular irrigation

Image: Nishal Lama for Forbes India[br]Following the success of the Karnataka project, the Maharashtra arm of 2030 WRG approached public and private players to begin a similar initiative in the state. “The project was started this May, and has 15 private and public players, including representatives of industry bodies,” says JVR Murty, consultant with 2030 WRG. “The project is sponsored by the CSR arm of ITC.”

The project covers areas in the districts of Pune (67,000 hectares), Sangli-Solapur (20,000 hectares), and Yavatmal (7,000 hectares), and approximately 40,000 to 50,000 farmers. “Unlike Karnataka, which was a greenfield project where they had to build irrigation systems, the areas in Maharashtra have existing irrigation options such as canals and wells,” says Murty. “Our aim is to bring 60 to 70 percent of the covered areas under drip irrigation systems, including sugarcane farmers.”

Local NGOs have been included to carry out a survey and analysis of the area, following which there will be capacity-building initiatives. “Along the lines of the Ramthal project in Karnataka, this too is for a time-frame of three years.”Working over longer timelines are organisations such as Professional Assistance for Development Action (Pradan), which works particularly among tribal and vulnerable groups to promote sustainable livelihoods. It aims to evolve the entire development ecosystem by collaborating with the government and donors. Pradan works with more than 7 lakh families in 7,920 villages in seven states about 70 percent of these people belong to vulnerable groups such as Dalits and indigenous communities.

By channelling interventions through women self-help groups (SHGs), Pradan promotes sustainable and organic farming methods, multi-cropping and crop diversification. “Empowering women farmers is key to ensuring food security,” says Sailabala Panda of Pradan, who works in the Rayagada district of Odisha. “Earlier, they did not know what rights they had on the land, and on the produce. But through social mobilisation, we have been able to improve their knowledge and skills, and also their income and standards of livelihood.”

While tobacco was the primary crop cultivated in the region till 2008, now small farmers grow a variety of fruits and vegetables that they are able to sell on their own, or consume themselves. Training and workshops through SHGs have also made women understand how to manage their finances, apply for loans, and gain a decision-making position in their families, and in society.

Back in Mandya’s Holalu, Kumar and his son Chandru stand on the terrace of their pumping station, surveying the expanse. Despite being the first convert to drip irrigation in the region for sugarcane, six years ago, he still farms paddy by flooding the field with canal water. Installing a drip irrigation system for paddy is a more expensive proposition, and the pipelines need to be rolled up for each harvest since they can be damaged in the process, and re-laid for sowing for sugarcane, the pipelines remain in place for up to five years since it is a ratoon crop.

Till the middle of August, the farmers had expected this to be a drought year. But then the rains arrived, and filled the rivers and dams. Peacocks now call in the distance as clouds gather over the vast expanses of lush farmlands. It will be a good season. But Kumar has enough experience to know it may not always be so. And change, perhaps, is on the horizon.

First Published: Aug 30, 2019, 15:31

Subscribe Now