The women who talk to trees

A new book combines scientific rigour with anecdotes and nostalgia to highlight the significance of trees in urban life

Harini Nagendra and Seema Mundoli, teachers at Bengaluru’s Azim Premji University

Harini Nagendra and Seema Mundoli, teachers at Bengaluru’s Azim Premji University

Image: Nishant Ratnakar for Forbes India[br]Ants are everywhere, but rarely noticed. Most people are indifferent to them marching along the walls of their homes, ignorant about the variety of species, and fail to credit them for the diversification of flowering plants. In urban Kerala, however, the presence of the yellow crazy ant indicates the pressures of rapid urbanisation. These ants, nesting in the leaf litter at the base of trees, are an invasive species whose presence in homes indicates a disturbed habitat. Groves of trees that are considered sacred by local communities of Kerala are home to more than 30 ant species, some of which are increasing in number as a result of rising human migration patterns and improper waste disposal.

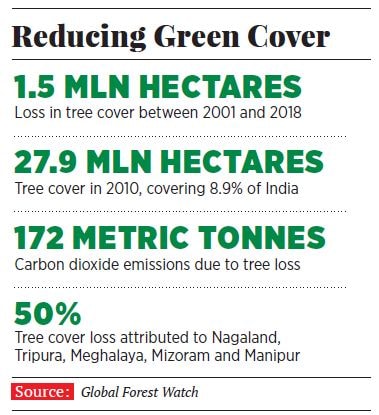

Many such facts, data and anecdotes are part of the research conducted by Professor Harini Nagendra and Senior Lecturer Seema Mundoli at the Azim Premji University in Bengaluru. Their body of work has examined the relationship between people and nature in Indian cities. Balancing historical references with fresh scientific findings, the duo has studied how changing lifestyles have impacted the importance of nature in daily life, how the government’s focus on infrastructure at the expense of green cover has changed the ecology of the country’s streets, parks, lakes, home gardens, slums and sacred spaces, and what this means for our collective future.

Some of these findings are published in a book titled Cities and Canopies, published by Penguin Random House and scheduled to be released on June 20. Nagendra and Mundoli discuss trees from a variety of perspectives, including exploring behavioural issues humans, especially children, face as a result of spending less time outdoors. “We want people to understand the science behind trees, while reminding them about the nostalgia, culture and livelihoods associated with it. This will help them take conservation more seriously,” says Nagendra.

The book includes data regarding the health hazards and climate change implications of tree felling, while delving into the history and changing utilitarian value of common urban tree species like the neem, peepul, jamun and eucalyptus. For instance, they present evidence from studies they have conducted to show how Bengaluru roads shaded by trees have temperatures of 23-24°C, whereas barren stretches are 3 to 5 degrees hotter. Nagendra explains that people usually talk about the weather in terms of ambient air temperatures, often ignoring that asphalted roads have surface temperatures often as much as 27° C higher than the air temperature. Concrete road surfaces also trap heat and release it at night, making a tree-less locality much warmer than the one with trees.“Reading about trees or being nostalgic about growing up around them is not enough. For people to care about saving them, they need to be more in contact with trees, experience them. Parents have a huge responsibility in making their children love trees,” says Mundoli.

TR Shankar Raman, scientist at the Nature Conservation Foundation, agrees the growing indifference to the importance of trees results in people merely shrugging at the inevitability of the loss of trees for development projects. “The disconnect between people and nature in cities is partly due to the mistaken belief that there is no place for nature in the city, and that the latter is something found in faraway forests or mountains,” he says. “Harini and Seema go a long way in dispelling this ignorance, making us appreciate trees around us anew.”

Tree Lover vs Development

The authors track how trees, which were the centre of life, trade and worship centuries ago, have become the first casualty for infrastructure projects. “This is because people began to see trees as less utilitarian,” says Nagendra.

This is perhaps corroborated by how, last year, the forest department cleared a proposal to chop off 16,500 trees for the redevelopment of central government accommodations in South Delhi. The year before, in Bengaluru, the government cleared a proposal to cut over 800 trees for a 6.7 km flyover between Basaveshwara Circle and Hebbal, to be built at an estimated cost of ₹1,791 crore. Protests from citizens have stopped both projects, similar to how they have delayed the construction of a metro rail shed in Mumbai’s Aarey green belt area after the Mumbai Metro Rail Corporation decided to cut 2,700-odd trees for it.

Nagendra explains that while taking a stand against cutting trees is increasingly viewed as anti-development, it becomes important to create awareness about inter-departmental cooperation so that they do not work in isolation. “There must be public consultation and full transparency about the environmental damage a project may cause. Planners and engineers must design public schemes in consultation with the forest department, rather than just approaching them for last-minute clearances. This would ensure that trees are a priority in development,” she says.

According to Raman, “Trees and urban biodiversity need to be integrated as vital components of cities in state policy and urban master plans… A more radical idea would be to offer a form of citizenship to trees: As urban citizens, local communities could act as guardians so that removal of trees without their consent can then be disallowed.”

Raghavendra Gadagkar, professor at the Indian Institute of Science, says Nagendra and Mundoli must be credited with a “special kind of paradigm shift where they are able to take rigorous scientific work to the common man”. “Scientists, ecologists and experts usually work on esoteric subjects, like forests or rare species. Harini and Seema are presenting studies that are much more important to the common man, in a manner that improves public awareness and understanding.”

First Published: Jun 11, 2019, 07:04

Subscribe Now