Taking the vitals of India's Smart Cities Mission

India envisioned a 100 smart cities to defuse its urban time bomb. Three years on, how close are we to an awakening?

(From left) Lipsa, Balia and Manas helped develop a playground for slum children in Bhubaneswar. Turning undeveloped plots into parks is a key agenda Metallic skyscrapers, manicured landscapes and a glitzy new airport dominate the glossy promotional video of Dholera smart city. While not technically part of the central government’s Smart Cities Mission, this industrial greenfield city, or Dholera Special Investment Region (SIR), 100 km south of Ahmedabad, was one of Narendra Modi’s pet projects when he was chief minister of Gujarat.

(From left) Lipsa, Balia and Manas helped develop a playground for slum children in Bhubaneswar. Turning undeveloped plots into parks is a key agenda Metallic skyscrapers, manicured landscapes and a glitzy new airport dominate the glossy promotional video of Dholera smart city. While not technically part of the central government’s Smart Cities Mission, this industrial greenfield city, or Dholera Special Investment Region (SIR), 100 km south of Ahmedabad, was one of Narendra Modi’s pet projects when he was chief minister of Gujarat.

Spread over 920 sq km—one and a half times the size of Mumbai—Dholera SIR is the biggest of the eight smart cities being developed under the $100 billion (around ₹6.80 lakh crore) Delhi-Mumbai Industrial Corridor (DMIC) project.

While the intention is to spur economic growth in the region, critics say the coastal area where the city is being built is not only flood-prone but will also displace small-scale farmers who live there. Environmentalists too are up in arms. Yet the construction of Dholera SIR carries forth.

As India races to build 100 new smart cities across the country by 2020 where does the country stand? The exploding urban population—expected to hit 590 million by 2030, up from 377 million in 2011, according to government data—calls for urgent solutions. But are smart cities the answer? Forbes India takes stock of the progress India has made so far on this front, including a deep dive into Bhubaneswar, the capital city of Odisha, which topped the ‘smart city challenge’ based on the quality of its proposals in January 2016.

*****

*****

Dubbed the ‘Indian Dream’, the Smart Cities Mission was launched with much fanfare in June 2015. State governments across the country were asked by the Centre to select three existing cities from their jurisdictions, engage with residents and come up with proposals of what a ‘smart’ version of their city entailed.

An expert committee evaluated the proposals received from cities and an initial list of the top 20 cities was released in January 2016. Another 13 cities were selected in May 2016, followed by 27 cities in September 2016 and another 30 in mid-2017. Nine more cities were added to the list earlier this year, including Bareilly in Uttar Pradesh, Erode in Tamil Nadu and Itanagar in Arunachal Pradesh, taking the total number of cities picked under the mission to 99. Shillong is expected to be the hundredth city.

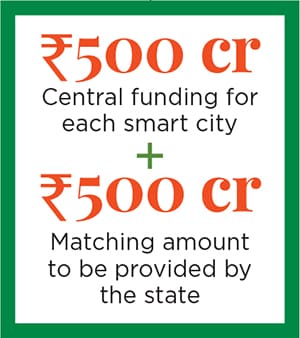

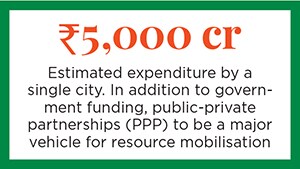

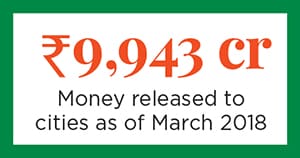

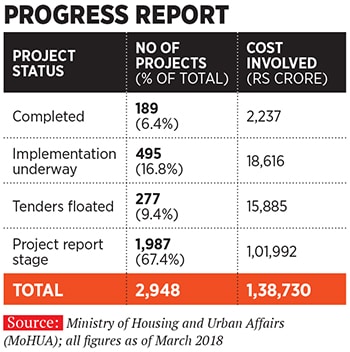

These cities—Bhubaneswar topped the list, followed by Pune—would receive ₹500 crore in funding from the central government to implement their plans. An equal amount, on a matching basis, would have to be contributed by the state or urban local bodies.But as of March 2018, implementation appears to be stuttering. Only 6.4 percent of the announced projects have been completed, while the lion’s share—almost 70 percent (see table)—are still in report stage, according to data released by the Ministry of Housing and Urban Affairs. Moreover, only 1.83 percent of the funds released to the cities have been utilised.

But Murty contends: “One has to look at this from three aspects. One is funds transfer, next is contracts awarded and third is funds utilisation.” With regard to the transfer of funds, he says most cities have received the promised central government funding.

As far as the other two pointers go, it depends on the nature of the project and delivery timelines, he says. Consider a ₹50 crore water pipeline project spread over four years. “The first year will go in consulting with experts to draw up the plans, so no money will be spent. Thereafter, tenders will be floated, contracts awarded and work will start. Payment will be released to the contractor in a phased manner. So it takes time,” he says.

Where progress can easily be measured is on the governance front. Most of the 99 cities have already set up a Special Purpose Vehicle (SPV) as required by the mission. Set up as a public limited company with the state and local body holding 50:50 equity shareholding, the SPVs are run by a professional CEO and are meant to bring about interdepartmental collaboration in implementing the smart city projects. “When building a road for example, the involvement of the PWD (to build pipelines), cable departments (to lay optical fibres), and the transport department is necessary. With the SPV, every city authority comes under its purview so implementation is faster,” says Murty.Using this structure, most cities have already begun work on a central command and control system that will use ICT to manage services such as water supply, sanitation, housing and waste management. Moreover, since cities are free to define what ‘smart’ means to them, projects are varied in nature—from a door-to-door garbage collection system in Jabalpur to ‘smart schools’ in Visakhapatnam with brightly-painted classrooms and better sports infrastructure.

Pune has put in place a public bike-sharing system with dedicated cycling tracks and the necessary infrastructure for private players to tap into. Bengaluru-based Zoomcar and Chinese startup Ofo have already deployed 1,200 cycles in the southern city through a public-private partnership (PPP). A total of 470 km of cycling tracks are being developed and over the next few months one lakh cycles will be deployed. To measure the success of such initiatives, the government has recently put to place a ‘Livability Index’.

Even so, criticism of the Smart Cities Mission remains. “India has 4,000 cities and towns. Why are we only looking at 100 cities?” asks Shivani Chaudhry, executive director of New Delhi-based civil rights group Housing and Land Rights Network India. Besides, mixed-income neighbourhoods, social housing and measures to improve women and children’s safety are lacking in most of the city plans, she says.Also, with the Atal Mission for Rejuvenation and Urban Transformation (AMRUT) and Housing for All launched along with the Smart Cities Mission in June 2015, it is unclear how the various schemes converge (or diverge). “Instead, the United Nation’s Sustainable Development Goals could have been integrated into urban plans and the money set aside for smart cities could have been spent more equitably across the country,” offers Chaudhry.

*****

Nothing really is happening on smart cities here,” says an executive at a Bhubaneswar-based company wth a shrug. “Something is happening but what exactly is happening we don’t know,” says a local shopkeeper when asked how Odisha’s capital city was faring on the smart city front.

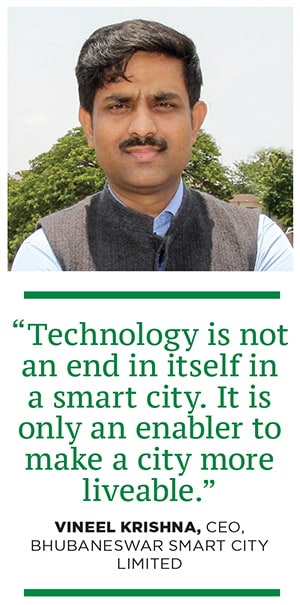

“A lot is happening. Look at these traffic signals,” says an auto driver pointing to the state-of-the-art adaptive signals with built-in cameras on Bhubaneswar’s arterial Janpath Road. Not only do they monitor truant drivers for breaking signals, but their built-in sensors will also talk to other signals on the road to smartly manage traffic. No need then to wait for a fixed number of minutes if there are no cars on the road the signals will sense that and automatically turn green. At the time Forbes India visited Bhubaneswar, in early-May, the sensor feature was to be rolled out within a few weeks.But the varying levels of citizen awareness about Bhubaneswar’s progress as a smart city points to a lack of communication between the authorities and those for whom the city is being revamped. “We do engage with citizens. But for changes to show on the ground and real impact to be seen, it takes time,” says Vineel Krishna, CEO of Bhubaneswar Smart City Limited (BSCL), the SPV responsible for rolling out the city’s smart projects.

According to him, ‘smart’ cities are ‘livable’ cities. “Technology is not an end in itself in a smart city. It is only an enabler to make a city more livable,” he says, adding that a key reason why Bhubaneswar topped the ‘Smart City Challenge’ was because of the strong focus on “child-friendly” elements. “When we think about cities, we usually only think about what adults need. Simple things like not making pavements very high so small children can climb on to them are often overlooked,” says Krishna, 38, an IAS officer who also serves as MD of the state-run Odisha Mining Corporation.

Turning undeveloped plots into parks for children is a key agenda. Already three ‘smart parks’ have been developed in a 1000-acre area dubbed Bhubaneswar Town District Centre (BTDC) along Janpath Road. Although bereft of technology, these parks include jungle gyms, basketball rings and jogging tracks all in ring-fenced, well-landscaped spaces.

In fact, BTDC has also tied up with Humara Bachpan Trust, a pan-India, not-for-profit that promotes safe and healthy living conditions for children in urban slums. The outfit serves as a conduit between the 24 low-income community areas that dot BTDC and the city authorities. Toilets, open spaces and reading rooms are some of the things children living in these impoverished areas want from a smart city, says Anwikshika Das, knowledge and operations coordinator at Humara Bachpan in Bhubaneswar.Regular discussions with Humara Bachpan empowered the children of Shanti Nagar, one of the slums that houses 80 families in BTDC, to group together and clear up a ground that had been used for open defecation for nearly 40 years, even though there were toilets adjacent to it. The kids tried teaching families the importance of sanitation, but found it was difficult to shake off people’s age-old habits. So they installed a camera at the entrance of the ground to scare off would-be culprits. People immediately started using the toilets. “Actually it was a fake camera,” says Balia, 25, one of the “youth leaders” who led the drive, grinning cheekily. Today, the open space, with brightly painted walls and a cricket pitch in the centre, is used as a playground, meeting point as well as a venue for weddings and festivities. Taking its cue, the Bhubaneshwar Municipal Corporation has also refurbished the toilets. “A smart city should take into consideration the views of urban dwellers as well as those living in communities. The authorities here consider our views,” says Lipsa, 24, another one of Shanti Nagar’s youth leaders.

On the ‘urban dweller’ front too, frenetic activity is taking place, ahead of the men’s hockey world cup that Bhubaneswar will host at the end of the year. For instance, Bhubaneswar Town Centre (BTC), a 12-acre site near the railways is being morphed into what Krishna claims is the country’s first “transit-oriented development”—a mixed-use development within walking distance of a transit station.

Surbana Jurong, the Singapore-based consultancy hired to implement the plan, has submitted its designs for the area which include elements such as a theatre plaza, malls and leisure amenities. “The town centre will be an enduring, walkable and integrated open-air, multi-use development… where citizens can gather and strengthen their community bonds,” says Wong Heang Fine, group CEO, Surbana Jurong. Similarly, multi-level car parks, a rental housing scheme for construction workers and homeless labourers as well as an integrated facility with a health dispensary, creche, library and skilling centre are under construction in BTDC. Pan-city projects include an intelligent traffic control system and a “common card payment system” that will facilitate public transportation, municipal services, and utility payments through a single card. However, as increasing amounts of citizen data is collected and stored, Krishna acknowledges that cyber-security measures will have to be tightened.

A total of ₹4,500 crore has been budgeted for all the smart city projects in Bhubaneswar, of which over ₹3,000 crore will come from public-private partnerships while the rest will come from the central and state government, says Krishna.

Taking a leaf from Bhubaneswar’s book, for cities to succeed as smart cities a dose of balance will be essential—between the glitz and grime, rich and poor, present and future.

First Published: Jun 01, 2018, 10:01

Subscribe Now