Symphony: Beating the heat with its air coolers

Missteps in diversification once pushed air cooler maker Symphony to bankruptcy. Wiser from the ordeal, founder Achal Bakeri is now taking the company global through acquisitions

Achal Bakeri, founder, chairman and managing director of Symphony, had sold out all the units that he had manufactured in the first year of production

Achal Bakeri, founder, chairman and managing director of Symphony, had sold out all the units that he had manufactured in the first year of production

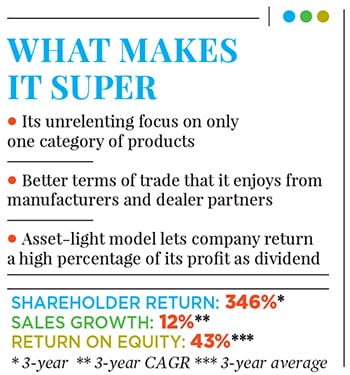

Image: Joshua NavalkarUnlike most entrepreneurs in the white goods segment, Achal Bakeri, 57, has not built factories with rows upon rows of assembly lines. Nor does his venture Symphony Ltd have a finger in every pie of the sector. A single-product company, it devotes all its resources to what it does best—making air coolers.

Symphony develops its products in-house and provides the tools for manufacturing, but outsources the final assembly to third party plants. Its employees look after vendor management and quality control.

It is this asset-light—and consequently capital-light—model that has made the stock a favourite among investors. Shares of Symphony, which could be picked up for a little over Rs 100 five years ago, were trading at Rs 1,364 on BSE on July 11, 2017—that’s a compounded annual growth rate of around 62 percent in the period.

More importantly, Symphony has chosen to return cash to its shareholders. Its return on net worth has always been above 30 percent in each of the last five years. “Returning excess capital to shareholders is the hallmark of a good business and shows that the interests of the promoters are aligned with those of minority shareholders,” says Utpal Sheth of wealth management firm Trust Capital.

Devoid of major heavy assets, Symphony has been modelled as a “product innovation, marketing and distribution company”, says Bakeri, founder chairman and managing director.

The result has been a clear pole position in the domestic air cooler market and financials that are in the pink of health. Revenues in FY17 grew to Rs 768 crore, clocking a compounded annual growth rate of 16 percent over the last five years. Profits, too, have kept pace, expanding at 22 percent a year in the same period, touching Rs 165 crore in FY17.

More recently, Symphony has created the niche market of industrial cooling wherein large factories, warehouses and halls are installed with Symphony’s air cooler units as a cheap alternative to air conditioning. Also, with two overseas acquisitions, the company has every chance of making a major dent in the international market.While the company has been asset-light from the get-go, the single-product strategy was adopted after missteps in diversification led to bankruptcy less than a decade after its first summer of sales in 1988.

Bakeri, a scion of realty major Bakeri Group, had started the business that year on his return to India after completing his masters in business administration from the University of Southern California. A year earlier, the family had installed an air cooler at their residence in Ahmedabad. While the cooling was satisfactory, “the product was an eyesore”, recalls Bakeri, who was convinced there’s a market for a more aesthetic product.

Symphony’s first air coolers had a dream debut. Though, at Rs 4,300, they were twice as expensive as the competition, it was still cheaper than an AC that cost around Rs 35,000 (for a 1.5 tonne unit) at the time. The first batch of about a thousand were sold out that summer.

Bakeri, who had seen his family struggle with collections in the real estate business, was clear that he would not extend credit to anyone when he started Symphony. Even today, the company pays its manufacturers upfront in exchange for cash discounts and supplies to dealers in exchange for immediate payment. (Well-known chains like Tata Croma and Vijay Sales, though, are allowed short credit periods.) This frees Symphony from the burden of working capital requirements—it does not have to borrow for its day-to-day operations.

After the initial success, Symphony progressively expanded sales across Gujarat and then across India, with the help of an aggressive marketing strategy. “In 1989, we might have clocked sales of Rs 3.5 crore, yet in 1990 we spent as much as Rs 1.8 crore on advertising,” says Himanshu Shah, director, sales and marketing, at Symphony. Liberal advertisement spends helped it become a national brand. In 1994, the company went public raising a little over Rs 10 crore. And then, the music stopped.

Being a publicly traded company, analysts, at meetings with Bakeri, stressed that Symphony is focusing on just one product, whereas competitors like Usha, Crompton Greaves and Polar were multi-product companies. Moreover, air cooler sales were dependent on a hot summer and Symphony needed a range of all-weather products, they opined.

Seeing reason in the argument, Bakeri started diversifying his product range in 1995 making, among other things, geysers and washing machines.

However, he had underestimated the competition in these categories. The next 14 years were the toughest in his life as he witnessed the net worth of his company erode. Compared to a profit of Rs 3.5 crore in 1994-95, the company posted losses of Rs 5.16 crore in 2000-01. As Bakeri told Forbes India in a 2015 story, “We spent seven years digging a hole and then seven years getting out of it.” In 2002-03, the company filed for bankruptcy and approached the Board for Industrial and Financial Reconstruction (BIFR), the government agency that assists in the revival of sick industrial units.  The market for industrial cooling is largely untapped and Symphony is looking to grow from scratch

The market for industrial cooling is largely untapped and Symphony is looking to grow from scratch

Having burnt its fingers trying to diversify, Symphony now decided to focus only on air coolers. It emerged from BIFR in 2009 to create Symphony 2.0 with a single-product strategy. The move came up trumps and eventually catapulted it to the position of market leader in air coolers. The battle-scarred Bakeri is candid in admitting that without the experience of seeing his company crumble, he would probably not have created the Rs 9,400 crore company (by market capitalisation as on July 11, 2017) that Symphony is today. And with the phoenix-like resurrection near complete, he is now expanding the global footprint, in what is Symphony’s third, and possibly most exciting, phase of growth.

While Symphony went about expanding in the domestic market, it is its two international acquisitions that provide further insight into the mind of Bakeri. Even as a global player, he retained the same asset-light model.

In 2008, the company acquired International Metal Products Company (Impco), which was started by Adam Goettl, who patented the first ever air cooler in 1930. After a series of ownership changes, the company had ended up in the hands of American private equity group Castle Harlan that was looking to sell. Symphony paid $650,000 (Rs 2.6 crore then) to acquire the company along with a debt of $25 million. The debt helped it get a tax write-off and the $650,000 Symphony paid was recovered within six months of operations.

“Their respect for capital is phenomenal and this shows in the [low] price they have paid for their overseas acquisitions,” says Nilesh Shah of Envision Capital, a value investing firm and a Symphony shareholder.

With Impco, Symphony lost no time in converting it into a low-cost operation. The company was put through the Mexican equivalent of Chapter 11 (a form of bankruptcy that involves restructuring a company’s debts and assets) and creditors were paid off a fourth of what they were owed. Real estate was sold and manufacturing was discontinued (coolers were supplied from India).

undefinedBakeri is now expanding the company’s global footprint, in what is its third and most exciting phase of growth[/bq]

Impco was a pioneer in industrial cooling and Symphony brought the product to India where it has been installed in places like yoga guru Baba Ramdev’s ashram in Haridwar, an L&T factory in south Gujarat, Decathlon stores in Ahmedabad and Ludhiana, a Hitachi factory in Ahmedabad and parts of the railway station in Kota. Bakeri says the market for industrial cooling is largely untapped and the growth potential is huge. “We have to create a market from scratch,” he says. “Many factories in India are very hot during summers. While installing air conditioning would be very expensive, we tell customers that air cooling is not only cost-effective but would also improve the productivity of workers.”

Even as the synergies with Impco were playing out, Symphony, in 2016, completed the acquisition of Chinese air cooling company Munters Keruilai. It paid Rs 1.55 crore for the company that had a thriving industrial cooling business. As Bakeri explains, “The market in China for air coolers is 20 times that in India but also very fragmented. So even a small slice of a large pie is a lot,” he says. Since the acquisition, Symphony has made China its base for industrial coolers, from where they are manufactured and shipped all over the world.

Importantly, even though Keruilai was acquired for a song, it had no debt and the book value of the company was higher than what Symphony paid. Bakeri quips that the promoters would have “given it for free”, given that it was a loss-making venture. Keruilai’s turnaround is still a work in progress and Symphony hopes to make it profitable by 2018.

For now, Symphony is also focusing on the export market. It sells across most of Europe, the Middle East, eastern Africa, Southeast Asia and Latin America. At present, 22 percent of its revenues come from overseas sales. Demand for air coolers as well as the recognition of the Symphony brand name have risen steadily abroad.

As the company has grown, Bakeri has also had to grapple with the challenges that entrepreneurs take while expanding. These include everything from installing enterprise resource planning software to getting the right people to work for him. Bakeri says this has proved to be less of a challenge than he expected. As the company has grown, they have found it much easier to attract the right type of talent. In any case, most of his top team has been the same since the company started in 1988.

For his foreign subsidiaries, Bakeri has kept the managements local. Indians do visit frequently but operations on the ground are left to those who understand them best. “All we ask for is vegetarian food when we visit,” says a company presentation.

Symphony’s business is largely on autopilot. The company continues to spend on advertising—Rs 41 crore in 2016-17, 32 percent higher than the previous year. And there is scope to grow. “Out of an estimated 250 million homes in India, only 25 million have air coolers, 10 million have air conditioners, and 60 million have fans,” says Bakeri.

Shah of Envision Capital says he was attracted to the business due to its long growth runway. “For the next 10-20 years, growth in this business is a given,” he says.

So is there anything that gives Bakeri sleepless nights? “Yes, the weather. That is the only thing we have no control over. A bolt of thunder in April can send our sales plummeting,” he says.

As for the rest, he seems to have his plans sorted.

First Published: Jul 25, 2017, 05:38

Subscribe Now