Motherson Sumi: The sum of all parts

A firm believer in long-term play, Vivek Chaand Sehgal set audacious goals and took a measured path to achieve them. The result: A global auto component behemoth and a shareholder's delight

When Motherson Sumi listed in 1993, it raised a paltry $700,000 from the market. The company had clocked Rs 12 crore in revenue and there was little to suggest that it would go on to become India’s largest auto component company. Few had heard of the Delhi-based maker of wiring harness and, as a result, not many gave it much of a chance. Few had also expected it to become a producer of a sizeable chunk of what goes into a car—think mirrors, air-conditioning systems, bumpers, spoilers and more.

But promoter Vivek Chaand Sehgal wasn’t perturbed. He, instead, was preoccupied with other, bigger plans. Sehgal, chairman of Motherson Sumi, had just acquired a new toy—a desktop computer. On his Microsoft Excel sheet, he plotted the carmakers’ projections. And what he saw surprised him. If it continued growing at its (then) current rate, Motherson Sumi would be on track to clock Rs 100 crore (in revenue) by 1999.Made as it was in 1993, this was an astounding claim. Consider that in the 20 years since Sehgal had started the company—this was while he was still in college—he had just about managed double-digit revenues. And now he wanted to increase it ten-fold in five years. This plan would need a serious reorientation in the way the company was run. But, at that point, an excited Sehgal didn’t pause for breath. He summoned his top eight executives and reported his findings. “Two of them thought I had lost my mind. The other six are still with me,” says the 59-year-old with a glint in his eye.

The glint is easily explained.

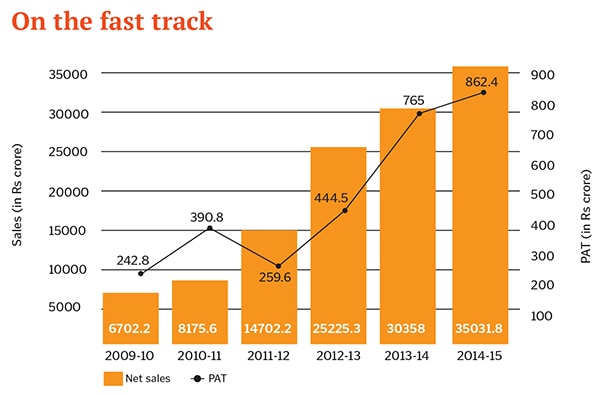

Fast forward two decades and Motherson Sumi, with business spread across 73 countries, clocked $5.5 billion (Rs 35,000 crore) in revenue for FY2015. (Samvardhana Motherson Group, of which it is a part, touched $7 billion.) In contrast, Bharat Forge, long held the poster boy of the Indian auto component industry, finished the year with sales of $1 billion (Rs 6,300 crore).

“I have no hesitation in saying that he has been our most successful vendor,” RC Bhargava, chairman of Maruti Suzuki, tells Forbes India. Sehgal had got his start by supplying to the country’s largest carmaker. “I won’t be surprised if Motherson’s turnover crosses that of Maruti’s in a few years,” says Bhargava.

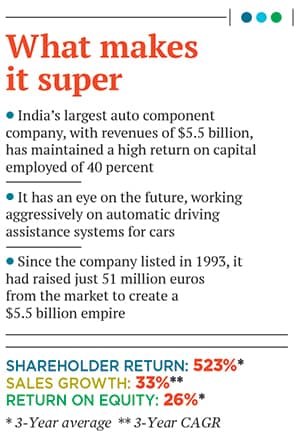

And this is no longer an outrageous notion. What makes Motherson unique is the incredible compounding machine that Sehgal has created: The company has managed high levels of growth with a high return on capital employed (RoCE). Over the last two decades, it has consistently returned 40 percent of profits to shareholders while generating a RoCE of 39 percent.

To ensure that the company and the group don’t step off the growth pedal, Sehgal announced, in May this year, his intention to take revenues to $18 billion for Motherson Sumi and $26 billion for the Samvardhana Motherson Group in five years. “Given the company’s track record in accomplishing its published targets, revenue targets seem plausible,” said broking house Prabhudas Lilladher in a May 2015 research note. Sehgal will be helped by son Laksh Vaaman Sehgal, 33, who runs Motherson Innovative Engineering Solutions and is working with an eye on the potential appetite for cameras and other high-tech gadgetry from driverless cars of the future. (Reason: These products have much higher margins.)

Sehgal’s past record makes it hard to question why he won’t make it. He has been consistently delivering on each five-year plan announced since 1993. This has been done, in part, by separating ownership and management and focusing on the long term growth. Since stepping down as managing director in 1996, Sehgal has been involved in plotting long-term strategic decisions for the company. He maintains a gruelling 250-days-a-year travel schedule and is always on the lookout for the next big business opportunity. It was this scouting that led to Motherson’s first major acquisition in 2009, of Visiocorp, the world’s largest mirror-making company.

This also enabled his son Vaaman to earn his stripes and propelled the company into the big league.

Entering the Big League

The movement started in November 2008, two months after Lehman Brothers had gone bust. Sehgal received a call from his customers—carmakers. UK-based Visiocorp, which made mirrors for the top eight global carmakers, was about to shut shop these auto majors wanted Motherson to take over the beleaguered company. On paper, it appeared to be an impossible task. Automobile sales had fallen off a cliff and Motherson was being asked to acquire a company that was about its own size—both had sales of 500 million euros (Rs 3,000 crore at that time).

Visiocorp, which was private equity-owned, had been run with the intention to prepare it for a sale. The short-term approach led the company close to a collapse during the financial crisis. If Sehgal failed to turn Visiocorp around, it could take all of Motherson Sumi down with it. Nevertheless, Sehgal and Vaaman decided it was worth the risk. They were both in the US at the time they took separate flights (they never fly together) to Bonn, Germany—Visiocorp has a majority of its manufacturing activity based there—and spent the next month locked in tense negotiations in a room with eight lenders who comprised the company ownership. They’d invariably spend the entire day discussing aspects of Visiocorp’s business, getting assurances from customers and looking at their manufacturing practices.

Meanwhile, at Visiocorp’s offices, the effects of the worsening financial crisis were being felt all too clearly. “We saw things going from bad to worse,” recalls Vaaman. “First the lunch stopped, then the tea stopped and then the toilets stopped being cleaned.”

At the end of the month, Sehgal submitted an offer, agreeing to take over the company for free. Now Sehgal was not someone to overpay for a business. Case in point, in 2005, Motherson Sumi had raised a 50 million euro bond for acquisitions. The company had kept it unutilised as Sehgal couldn’t find a good deal to spend it on. Here, too, he’d reasoned that with Visiocorp bleeding cash, and with no buyers, the owners would be happy to offload.

He had miscalculated. This offer was summarily rejected by the eight hedge fund and private equity owners of the company. Father and son packed their bags and came back to India. With no certainty about the future, they believed there was no need to overpay. Or in this case, pay.

But as things got worse, the company’s customers continued to look at Motherson for a reprieve. The Indian company, in turn, continued to hold steadfast on its resolve to not overpay. Things got worse, another round of negotiations resulted in failure—and, in February 2009, The Economist reported an 82 percent decline in truck sales by Volvo. This served to drive home just how poor automobile sales were in Europe for Visiocorp’s customers.

Then, in March 2009, after General Motors announced bankruptcy, Motherson was called yet again for another round of negotiations. Pankaj K Mital, chief operating officer of Motherson Sumi, recalls an inspiring speech that Sehgal had made to his eight employees in Germany. “There could be a hundred reasons to not do this deal but even if there is just one reason to do it, we should,” Sehgal told them. Acquiring a company of a size comparable to that of Motherson’s during a massive slowdown in car sales was no small task. Even so, when the eight people were asked to vote, they all voted yes. “My father still has those pieces of paper that we voted on,” says Vaaman.

Inevitably, the post-purchase phase wasn’t a smooth ride. Sehgal realised that decisions had been taken with a short-term outlook and that the business was bleeding cash. In Germany, if a business runs out of cash, the chief executive is held liable and can even be jailed. At that rather tumultuous stage, Sehgal took a decision that shocked many within the company. He decided to name the then 27-year-old Vaaman as chief executive. “Of course we would never have allowed him to go to jail but that was the best training I could give him,” says Sehgal.

For the next four years, Vaaman was put through the paces. He toured Visiocorp’s (since renamed Samvardhana Motherson Reflectec) facilities relentlessly and worked on making processes more efficient. He learnt German. He also made personal calls to his customers—Volkswagen, Audi and Porsche among others—so that orders started flowing in once automobile sales resumed.

Within a year, Visiocorp was making a profit and today, it accounts for $1.3 billion in sales for Motherson. Not bad for a company that Sehgal acquired for $21 million at the height of the financial crisis. More importantly, with this acquisition, Motherson had gained global scale, global customers and global ambition.

The Secret Sauce

Motherson’s success can be traced back to three decisions taken by Sehgal in the 1990s. At that time, there was little that set Motherson apart from other component makers. Sehgal was not happy with the pace of growth and knew he would have to grow much faster than the industry to have a chance of becoming the largest. To that end, here’s what he did:

First, Motherson decided to increase the amount of components it supplies to a car. It all started by accident. In 1995, the Indian government introduced the Phased Manufacturing Programme, which was a euphemism for forcing auto manufacturers to localise content. Motherson, on its part, imported a plastic moulding machine and since it couldn’t get enough business, it asked manufacturers for ideas on what more it could do. That was when it gradually started moving from supplying only wiring harness to plastic parts as well. That also opened its eyes to how it could outpace the industry.

Second, Sehgal decided to codify his ambitions and move out of the day-to-day operations to focus on long-term goals. “It gives the company a lot more focus,” he says.

In 1993, the Rs 100 crore-target energised his team but Sehgal hadn’t put it down on paper. He knew it was a mistake and, come 1999, he wasn’t going to repeat it. This time he decided to aim for another ten-fold jump, to Rs 1,000 crore by 2005. He also said the company would maintain a 40 percent RoCE. “As a result of this, we started reviewing all our operations from a RoCE perspective. Every bit of machinery we bought was evaluated using this parameter. All inventory was stocked using this in mind,” says GN Gauba, chief financial officer at Motherson Sumi.Third, unlike its rivals, Motherson Sumi always relied on its customers for leads on businesses to acquire. “Unlike others, we don’t deal with bankers when deciding what to acquire. Only if a customer wants us to do an acquisition do we do it,” says Vaaman. “That way we are assured of business.”

By now, Motherson has set up a well-oiled machine called the corporate office in Europe that assesses potential targets. They are so selective that they have a 5-6 percent deal closure rate and don’t hesitate to walk away if the price is not right. Only those businesses are bought that are cheap and can be turned around. One such company is Peguform, a world leader in dashboards, door panels and bumpers. Acquired for a song in November 2011 (the company declined to disclose the amount), it now contributes 1.9 million euros to Motherson Sumi.

The Road Ahead

Having built a $7 billion empire from scratch, the ever restless Sehgal is already thinking of the next big opportunity. The father and son duo is positioning the company to take advantage of automatic driver assistance systems (ADAS). Leading the charge is Vaaman who, after spending four years in Germany as CEO of Samvardhana Motherson Reflectec, now oversees Motherson Innovations, which is working on patented technology. The company is very clear that the connected car is the future.

Filled with advanced electronics, these would be far more profitable for component manufacturers. Margins could easily be twice that for windshields and bumpers. It is a slice of this business that Motherson wants to muscle its way into.

The argument: As cameras get cheaper, manufacturers are more likely to use them. Earlier cars came with radars that were more expensive and harder to use. Vaaman envisages the cameras replacing mirrors and lamps in a car as is already happening in some high-end models of sports cars like the Porsche and Lamborghini. To this end, he has set up offices in Silicon Valley (US), Germany and Australia to work on this technology while the testing and validation are done in Bengaluru, a low-cost location.

Sehgal paints a futuristic picture of a tired golfer using automatic driving technology to drive back home after a game. The car would run along the highway at a sedate 60 kmph while the golfer grabs a quick nap. He envisages that 35-40 percent of the value of a car could be comprised of this top-end gadgetry. At present, the global market for such cars is about 35-40 million vehicles. At $100,000 for each vehicle, it is a $35-40 billion opportunity.

If Motherson has to reach its $18 billion in sales target, Vaaman says a “significant portion” of that would have to come from electronics. In addition, the company would have to compound at 26 percent a year— something it has shown it can do.

Towards the end of our interview, Sehgal relays yet another unbelievable statistic. Since the company listed, it had raised just 51 million euros (Rs 350 crore today) from the market to create a $5.5 billion empire. Simply put, shareholders investing Rs 2,500 in 1993 would be worth Rs 58 lakh. In addition, they would have received Rs 14 lakh as dividend. It is a record no other Indian auto component maker has come close to. And one that would have been scoffed at in 1993.

First Published: Jul 20, 2015, 06:15

Subscribe Now