Eicher Motors: It's all in the drive

A substantial part of Eicher Motors' success story can be attributed to Siddhartha Lal's conviction in Royal Enfield, a struggling business back in 2000

The same passion had, four years earlier, helped him thwart an attempt by Eicher Motors, the flagship company of the Eicher Group, to sell or close down Royal Enfield. The iconic Bullet motorbike, despite its die-hard enthusiasts, had been facing several roadblocks at the time. Demand was low with sales barely crossing 2,000 units a month against the production capacity of 6,000. Reliability issues such as engine seizures, oil leakages and electrical failures were rampant and the bike was increasingly being seen as too difficult to manage. Also, emerging emission and other regulatory norms raised questions about the future of the bikes. The Eicher Motors management did not see value in the bikes: They contributed only a fraction of the overall business, which included commercial vehicles.

However, Lal, who had just completed his Masters in automotive engineering from the University of Leeds, UK, viewed the situation differently. “Royal Enfield’s bones were good and it was in a segment that had a promising future,” he tells Forbes India. Conviction in hand, he asked his father Vikram Lal for two years to effect a turnaround.

Lal Sr did well to listen to his son.

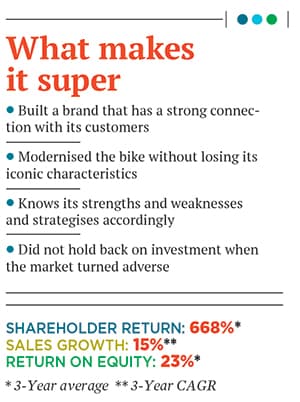

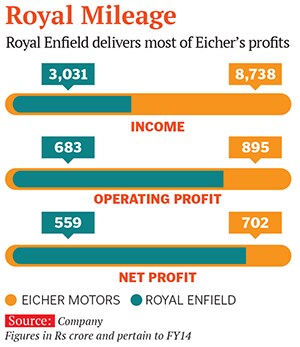

Fifteen years later, Royal Enfield contributes 40 percent of Eicher Motors’ turnover, 80 percent of its operating profit (Ebitda) and almost all of its net profit as per first quarter results of 2015-16 (the company’s financial year began on January 1 and will culminate after a 15-month period on March 31, 2016). As a business, it has grown consistently at a compounded annual growth rate of 50 percent over the last three years. Its operating profit margin is 24 percent and it has a market share of 96 percent in the mid-weight (250 cc to 750 cc) leisure motorcycle segment, which includes global players such as Harley Davidson, Ducati and Triumph. Despite a five-fold increase in capacity in the last four years, the waiting period averages between two and four months. “Our ability to sell is constrained by our ability to produce,” says Rudratej Singh, president, Royal Enfield. Some might call it a happy problem. Investors have rewarded this transformation and the Eicher Motors stock has risen from around Rs 22 in 2000 to Rs 19,000 levels now.

Authentic versus Modern

But change is never easy, as Lal was to find out. For one, the Bullet buffs wanted the bike to remain authentic. This meant the cast-iron engine and the gear box should stay separate (which was causing oil leaks), brakes should be on the left-hand side (the opposite was true for all other bikes) and persisting with the existing, difficult kick-start instead of an electric one.

Lal, therefore, had to consider whether his attempt to modernise the product and attract new buyers would result in alienating existing customers. “If we had listened only to the hardcore enthusiasts and retained everything authentic, we would have failed. More than the loudest voice, we had to listen to the unsaid voices—people who wanted to buy a Royal Enfield product but were dissuaded by reliability and other issues,” says Lal, today the managing director and CEO of Eicher Motors.

How did he strike a balance? The classic design, the ubiquitous thump and the low torque were retained changes such as a shift to an aluminium unitary engine with the gears and the engine as a single unit, disc brakes placed on the right and an electric starter were introduced. In some cases, that meant working against the laws of physics. For instance, the aluminium engine, with 30 percent less moving parts and 30 percent more power, failed to reproduce the loud thump that Royal Enfield bikes were known for. International consultants were called in and sound mapping was conducted to find a solution. Extending the exhaust pipe helped but the final decibel level was still 30 percent lower than earlier.

“It is a remarkable story of how a physical product was modernised without the brand losing any of its characteristics that gave it the iconic status,” says Professor Abraham Koshy, professor of marketing, Indian Institute of Management (Ahmedabad), who also co-authored Marketing Management—A South Asian Perspective along with Philip Kotler.

Lal also changed the way the bikes were sold—from rickety, basic, even dirty shops in dingy bylanes to state-of-the-art showrooms in upscale areas like Delhi’s Khan Market. Over the years, the company also widened its product line to include, apart from the traditional Bullet, models such as Classic, Thunderbird, Desert Storm and Continental GT.

Sales began to rise and soon demand started to overtake capacity. In 2011, the company had sold 74,626 bikes this figure jumped to 1.78 lakh units in 2013 and to 3.02 lakh units in 2014. The target is to close 2015 at 4.5 lakh units. “Today we are selling whatever we are producing. Not able to meet the surging demand is a good problem to have but we are expanding consistently to ensure that our customers need not have to wait long for their bikes,” says Singh. The manufacturing capacity at Royal Enfield will touch 6 lakh units by March 2017, he adds. Eicher invested Rs 600 crore during 2013 and 2014 and will put in another Rs 500 crore in 2015. The bulk of these funds have been used for capacity expansion. But this appears insufficient as the order book continues to overflow.

Royal Demand

“Royal Enfield enjoys a unique position among Indian premium motorcycles as its distinctively-styled bikes fulfil the customer’s key aspiration of owning differentiated products at a reasonable price,” says Nitij Mangal of CLSA, a broking and investment firm, in his latest report. Says Lal, “At a time when manufacturers launch newer models every year, forcing customers to upgrade, we offer bikes whose look and feel has not changed for the last 80 years and will not change for the next 80 years.”

The brand’s individuality, in a largely commoditised world, sells. “What bike you ride communicates who you are. Royal Enfield has successfully positioned its products as a quintessential macho man’s bike. A product like Bullet, for instance, differentiates the rider from the crowd of commuter bikes on the road,” points out Koshy. Unlike other two-wheeler manufacturers, Lal isn’t the one to go for a publicity blitz. “We don’t feel advertisement is a way to build a lasting brand,” says Lal. So much so that when he was looking to hire someone to head Royal Enfield, he initially avoided FMCG executives. “They tend to think only above the line,” he adds. But eventually he chose Singh, an 18-year Hindustan Unilever (and 20-year FMCG) veteran. “Singh had an orientation similar to us,” Lal explains quickly. “It is to promote riding instead of just selling the bikes.” The company organises riding excursions like the Himalayan Odyssey and Tour of Tibet to add value to the brand. There are numerous Royal Enfield clubs that dot the country, with each conducting its own rides. “Our evocative bikes have the capacity to connect man, machine and the terrain in unison,” says Singh.

But Royal Enfield has still not fully leveraged the strong pricing power it has in the market. “The company has exercised some prudence by not taking up prices too much so as to expand the overall market rather than solely maximising profitability,” says Mangal in the CLSA report. Eicher’s CFO Lalit Malik sees no reason for upping prices. “Raising prices is the easiest lever to improve profitability. We are looking at more challenging options like improving operating ratios,” he says.

That is already happening on the ground. With volumes ramping up over the past few years, fixed cost as a percentage of sales has declined sharply from 17 percent in 2010 to 10 percent (in Q1 of FY16). This has also brought down material costs to less than 60 percent of sales as against 70 percent five years ago. The operating profit margins have thus touched the highest levels of 24 percent in the first quarter of this year. “We are not a luxury brand. For us, the miracle happening in the marketplace is because we are seen as an affordable and aspirational lifestyle brand,” adds Malik. This pricing policy has ensured that Royal Enfield products do not have much competition. Its costliest bike Continental GT is priced at Rs 2.25 lakh while the price of Harley Davidson Street, its nearest competitor, is Rs 4.33 lakh. Other products from Triumph and Ducati are priced even higher.

The strong demand, little competition and high margins that Royal Enfield enjoys may not last forever and Lal is aware of this. He is already putting in place a strategy that will power the company for the next 15 years. “We are one platform and one country but that is changing,” he says, hinting at both geographical and product portfolio expansion. In India, the company is deepening its distribution network and will be adding hundred-plus dealers in the next two years. It will drive thought leadership through the launch of new engine platforms (and bikes), new gear and new stores. Outside the country, it has started taking steps to become a global brand. “A big position is available in the global market where the middle-weight category has not been adequately addressed. That is the next big journey. We need to build a brand truly relevant in the international market,” says Lal.

The company has created a 300-strong technical team in India and the UK to come up with cutting-edge design and technology. The UK centre, headed by Pierre Terblanche, a leading design mind from Ducati, will focus on larger bikes in the 250 cc to 750 cc category while the Chennai centre will work on smaller bikes. “Both centres will work in tandem and share knowledge,” he adds. The company has already tasted early success in international markets, like the UK and Colombia. Last year, exports grew 46 per cent.

The Truck story

While Lal chose to revive and create a strong brand on his own in the motorcycle business, he did the opposite when it came to Eicher’s truck business. “With trucks, it was not a turnaround story. We were only a segment player present in the 5-15 tonne category in a market dominated by two large players—Tata Motors and Ashok Leyland,” he says. That apart, many multinational companies such as Daimler, Scania and Mann had announced plans for India. To face emerging competition and to take advantage of future growth, Eicher Motors needed capital, technical capability and reach. “It was clear that a good partner who believed in the same future—modernising the Indian trucking sector—would help,” says Lal. In Volvo, Eicher found such a partner and Volvo Eicher Commercial Vehicles Ltd (VECV) was set up in 2008 with a 46:54 shareholding with Eicher holding the majority. “Rather than having the whole of a small pie, I felt it was better to have a smaller share of a larger pie,” he says.

Volvo and Eicher have complementary strengths. “Volvo has world class technology as well as processes and we have our frugal methods of product development,” says Vinod Aggarwal, CEO, VECV. In the first three years (2008 to 2011) of the joint venture, volumes doubled from 24,000 units to 48,000 and then recession struck. VECV closed 2014 with sales of 40,000 units. Though the JV is yet to realise its full potential, it has begun to show some results. “In the light- and medium-duty segments, our market share has risen from 28 percent since the formation of the JV to 33 percent in 2014. In buses, the share has grown from 6 percent in 2008 to 15 percent in 2014. In the heavy-duty truck segment, the VECV market share has risen to 4 percent from 1 percent in 2008,” says Aggarwal.

But Lal did not sit idle during the longest recession in the history of the Indian commercial vehicle sector. VECV has invested Rs 2,300 crore in the last four years to set up an engine plant that produces Euro VI compliant engines for Volvo’s global use. A new bus body building plant has also been commissioned and Eicher’s truck plant has been modernised and expanded. The company has also adopted Volvo’s processes in manufacturing, quality control, product development, after-sales and marketing. “The most significant is the development of an entire range of trucks and buses by adopting Volvo technology in our frugal ways,” says Aggarwal. “We are launching an entire line of ‘Pro-series’ products from 5 tonne to 49 tonne.” Says Lal, “In three years, the Pro series will modernise trucking in India.” And as the person who ensured that the Bullet continues to rev, Lal is a difficult man to doubt.

First Published: Jul 22, 2015, 06:20

Subscribe Now