Modern gurukul: Why management schools need an upgrade

Outdated curricula and mediocre B-schools have made the MBA degree less coveted than before. Only those that invest in prepping millennials for a new-age workplace will thrive

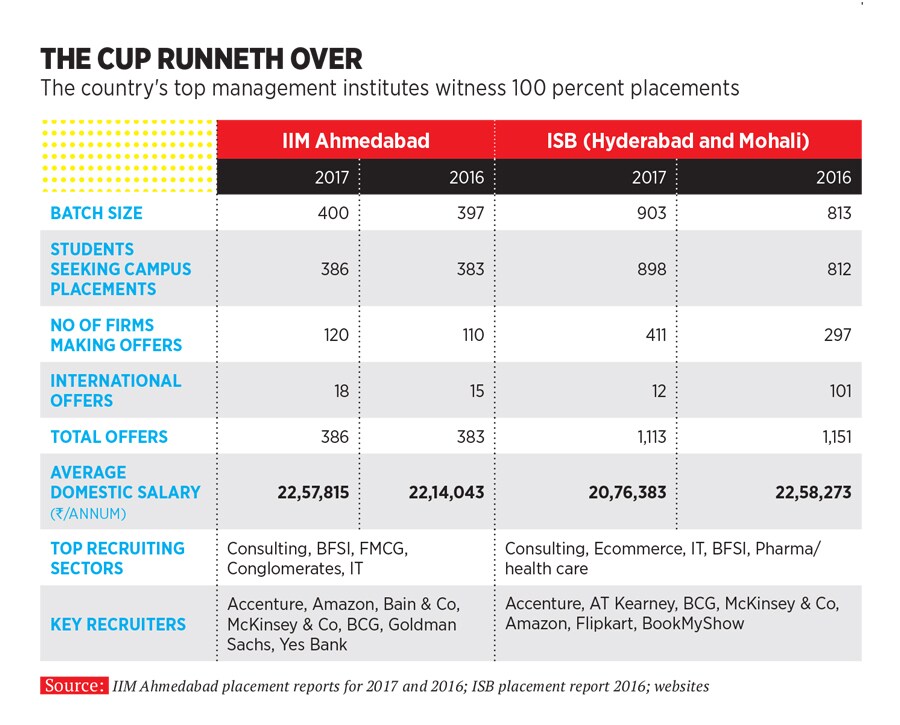

Though institutes like ISB continue to witness 100 percent placement, management education, in general, is staring at a grave crisis

Image: Harsha Vadlamani for Forbes India

When Adi Godrej, the 75-year-old chairman of the $5-billion Godrej Group, joined his family business in 1963, he was the first management graduate in the family to do so. “The concept of management education was unheard of in India at that time,” Godrej tells Forbes India.

After completing his management studies from the Sloan School of Management at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Godrej joined his family’s soaps business and utilised his global education to usher reforms that helped turn the venture around. Realising the value that a management graduate can bring to an enterprise, Godrej hired more such candidates at the conglomerate, including from the first graduating batch of the Indian Institute of Management Ahmedabad (IIMA).

Management education in India has come a long way since then. MBA: These three letters (an acronym for Master of Business Administration) represent the pillars on which millions of young Indians have built their careers, dreams and aspirations over the last five decades. The success achieved by the first few batches of the IIMs in India and abroad (think KV Kamath, Raghuram Rajan and Indra Nooyi) spurred the creation of a plethora of other public and private sector B-schools in the country.

A brewing crisis

Management education, along with engineering, formed the very fabric of the universe of so-called white-collar professionals in India. But much like engineering, management education in the country is also staring at a grave crisis.

The reasons for the current disenchantment experienced by millennials are broadly the same. While an increasing number of B-schools and engineering colleges have mushroomed in an unregulated environment, focus on the quality of education has suffered, dimming job prospects for students.

“The industry-academia connection in Indian technical education is lacking. Courses on campus are too focussed on writing and clearing exams, and not on what businesses really need,” says K Sudarshan, managing partner, India, at EMA Partners, a global executive search firm. “The pedagogy at these institutes is more theoretical and bookish, with no real application of what one learns.”

It is no surprise then that an overwhelming majority of graduates from such schools are found to be unemployable by the industry. According to industry body The Associated Chambers of Commerce & Industry of India (Assocham), only 20 percent of students graduating from B-schools in 2017 have got employment offers. According to the Assocham report, many parents and students are rethinking before investing several lakhs of rupees for a course. “More than 250 B-schools have closed down since 2015… another 99 are struggling for survival,” the report states. “The root cause of the problem is that institutes only focus on filling up seats and do not consider the quality of students at the time of intake. Consequently, students think that the entire responsibility lies with the institute. On the other hand, the institutes will have to improve the infrastructure, train the faculty, work on industry linkages and spend money on research and knowledge.”

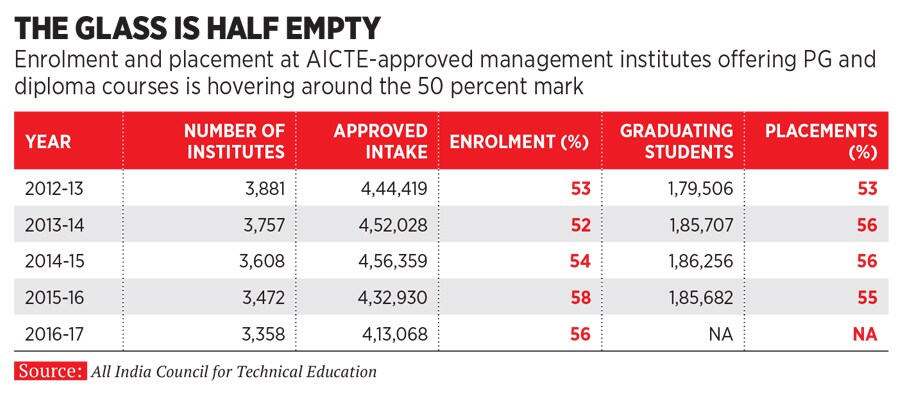

According to data available with the All India Council for Technical Education (AICTE), only half the students graduating from B-schools approved by it are getting placed. (See table The Glass is Half Empty)

There definitely are some top engineering and management colleges that have built a reputation of being premier institutes. But these cater to only a small fraction of job aspirants who think a degree in engineering or management, or both, is the best way to enter the workforce.

Forbes India spoke to a number of academicians from leading B-schools in the country and HR heads of large companies to assess what can be done to reimagine management education so that the MBA course regains some of its lost sheen. Five distinct areas on which management schools need to focus on emerged. Bala V Balachandran, founder, dean and chairman of the Great Lakes Institute of Management says his institute encourages students to start their own businesses on campus

Bala V Balachandran, founder, dean and chairman of the Great Lakes Institute of Management says his institute encourages students to start their own businesses on campus

Image: P Ravikumar for Forbes India

Technology

Gone are the days when technology was the sole domain of technologists. “The workplace of 30 years ago is different from the one today. We need to teach skills that are relevant in the present context,” says Nitish Jain, president and director, SP Jain School of Global Management, which has campuses in Mumbai, Dubai, Singapore and Sydney. “Business education and technology were two separate streams to date. But they are merging as new businesses are increasingly being led by technology.”

Consequently, SP Jain is reconstructing its entire MBA programme to make technology an integral part of it. The institute now has separate virtual labs focusing on blockchain, Internet of Things, machine learning, Artificial Intelligence, and big data, all hosted on the cloud and accessible from anywhere. The school is hiring faculty trained in such new technology, who can help students (and even the alumni) make sense of how the current wave of digital transformation is disrupting businesses through courses such as 3D visualisation of MIS data, and how to make supply chain management and marketing more efficient using technology.

Apart from including technology in their curriculum, B-schools are also leveraging it to expand their reach. “Access to quality education is enhanced by enabling distance education, either in a synchronous or asynchronous mode,” says G Raghuram, director of IIM Bangalore (IIMB). “The MOOCs (massive open online courses), offered by IIMB are an example of this. Over 500,000 students, across 189 countries, have registered for IIMB’s 30-plus MOOCs.”

Manav Jain, associate vice-president, human resources, at Paytm, says the gap between the top tier B-schools and those in subsequent tiers keeps widening when it comes to the focus on technology. “While there are electives or subjects around digital marketing or digital analytics, it’s more of a hands-off approach,” says Jain. “From a curriculum standpoint, there is scope for improvement.”

Entrepreneurship

For long, the end objective of an MBA degree was a well-paid job in the corporate sector. But times have changed. With relatively easier access to funding, several B-school students want to utilise their intellectual capital and training in management studies to turn entrepreneurs, right out of campus, and sometimes even while on it. But traditional MBA programmes are still geared towards creating future employees rather than entrepreneurs.

At the SP Jain Institute of Management Research (SPJIMR, no connection with SP Jain School of Global Management) in Mumbai, students from the graduating batch are allowed to defer their placement by two years to try their hands at entrepreneurship. “We provide these students a stipend for two years and mentor them,” says Ranjan Banerjee, dean of SPJIMR. Additionally, SPJIMR has its own incubator for students who are a part of the entrepreneurship cohort.

“We are recognising that even if students want to turn entrepreneurs, the prospect of needing to borrow funds and the need for security deter them at the beginning of their careers,” says Banerjee. “So 3-4 years down the line, if an alumnus wants to pursue a business, we extend our help to him as well.”

The industry is also doing its bit to work with MBA graduates. Mahindra & Mahindra (M&M) has a programme called Mahindra War Room, where live business challenges are thrown at MBA graduates. Those who take these on, work on them for 45 days and come up with solutions that are presented to M&M’s Executive Chairman Anand Mahindra and other group presidents. “The event not only helps bridge the industry-academia gap, but also upskills students by providing them an opportunity to apply their management education to real-life problems,” says Prince Augustin, executive vice president, group human capital and leadership development, M&M.

“We believe that an entrepreneurial spirit and skillset are key enablers for driving exponential growth in the organisation,” says a Hindustan Unilever spokesperson.

Research

A regular criticism of Indian B-schools has been that they don’t focus enough on research. As has been demonstrated by global B-schools, most notably the Harvard Business School, high quality research helps build an institute’s brand from a thought leadership standpoint and attracts the best minds. Raghuram says research is an “essential part of management education” at IIMB, and helps keep the curriculum “current and rigorous”. Calling his institute a frontrunner in the field of research, Raghuram cites that IIMB’s faculty members had as many as seven research papers published in the Financial Times Top 50 Journals in 2017 alone. The subject of such research has varied from how foreign companies can be successful in their ‘Make in India’ vision by weaving together global and local supply chains, to how careers are shaped post adult onset of hearing loss.

Raghuram says research is an “essential part of management education” at IIMB, and helps keep the curriculum “current and rigorous”. Calling his institute a frontrunner in the field of research, Raghuram cites that IIMB’s faculty members had as many as seven research papers published in the Financial Times Top 50 Journals in 2017 alone. The subject of such research has varied from how foreign companies can be successful in their ‘Make in India’ vision by weaving together global and local supply chains, to how careers are shaped post adult onset of hearing loss.

SPJIMR has roped in R Gopalakrishnan, former Tata Sons director and vice chairman of Hindustan Unilever, as executive-in-residence, who will spend four days a month on campus to work on applied research projects. “The flaw with research is that it stays confined to academic journals. We want to do research that will impact the way managers think and act,” says Banerjee.

Ethics

In the light of various instances of corporate greed that have come to light globally over the last decade, there is a rising demand for the business leaders of tomorrow to be ethical and sensitive to all stakeholders, including the community around them.

Banerjee says while almost all institutes have some course or the other on ethics, not all of them are effective. To sensitise students to the society in which they operate and make them more empathetic leaders, SPJIMR mandates its students to take up a social sector internship, requiring them to spend five weeks with a rural NGO. “So some part of the ethics course is taught through experiential learning, which is a significant differentiator,” says Banerjee.

SPJIMR revamped its ethics course in 2017, making it compulsory for students to interview 50 CEOs and understand first-hand the kind of moral dilemmas they face, and how they have stayed the course while adhering to certain principles.

undefinedJust 20% of students graduating from B-schools in 2017 have got Job offers[/bq]

Nitish Jain states that if and when a student at SP Jain School of Global Management is caught cheating, apart from penalising him, there is also an intense counselling session that he needs to undergo. “The idea is to try and reform such students and if you persist with them, it works,” says Jain.

“We have always ensured that the values of ethics and corporate governance are intrinsically embedded in our employees and therefore we continue to check for the same when hiring any new recruits,” the HUL spokesperson said.

Diversity

“A heterogeneous peer group offers the greatest bandwidth in being able to understand perspectives that differ on the basis of culture, ethos, age, experience, qualification and ethnicity,” says Balachandran.

For long, management education in India has been dominated by male students, who comprised an overwhelming majority of a class, and engineers. This led to lopsided peer groups where technical thinking would take precedence over creative differences.

Some progressive institutions have started taking steps towards carefully constructing a classroom that will allow for a free flow of divergent views. SP Jain School of Global Management, for instance, restricts engineers to 50 percent of a batch strength. The other half of the class is sourced from diverse backgrounds such as professionals from the fields of fashion, hospitality and law. “Just because someone scores higher on an aptitude test, it doesn’t make him a smarter business manager,” says Nitish Jain. “Which is why we put a lot of weightage on panel discussions with our faculty and alumni during the admission process.”

At SPJIMR, female students comprise 42 percent of the class while Great Lakes tries and ensures a healthy mix of students from all regions of India.

Sudarshan of EMA Partners observes that if B-schools continue to breed mediocrity, India may alarmingly find itself at the beginning of another phase of brain drain, after witnessing the first one in the 70s and the 80s, when those with resources relocated to countries like the US and UK in search of greener pastures. India’s middle class has more economic heft than it did four decades ago and global B-schools are more than eager to woo Indian students. The only way homegrown management schools can compete is by continuously upgrading their curriculum, faculty and infrastructure, and producing talent ready for a modern workplace.

First Published: Jan 16, 2018, 06:53

Subscribe Now