Swiggy vs Dunzo: A battle for hyperlocal 2.0

After a catastrophic start, hyperlocals are back in vogue with the startups locking horns. Will Dunzo survive Swiggy's incursion?

Swiggy has managed to survive the downfall of hyperlocal startups that started in late-2015 due to lack of capital

Image: Joshua Navalkar

They shot to fame real quick, but their fall was even quicker. The general consensus was that homegrown on-demand hyperlocal startups were destined to go bust. Most of them eventually did. But that was some years ago. The playbook has been rewritten and the war bugle has been blown again. At stake is an opportunity to win over consumers with instant gratification. “Speed is like a drug,” says Shivakumar Ramaswami, founder of IndigoEdge, an investment bank. “If you can deliver goods real fast, customers will be loyal. That is the thesis (of hyperlocal).”

Competing fiercely for this loyalty are Swiggy, a food delivery unicorn that survived and thrived in the punishing years beginning late 2015, when calamity first struck the hyperlocal populace, and Dunzo, an upstart that seems to be at ease playing David to Swiggy’s Goliath.

The duel has brought the spotlight back on hyperlocal, which, despite the initial promise, was perceived as businesses that brought misery to stakeholders. And rightly so. Most of the early proponents of hyperlocal in India such as Grofers, PepperTap, ZopNow and TinyOwl among others were badly bruised.

Swiggy and Dunzo seem to have learnt from the mistakes of their peers. Unlike yesteryear’s vertical-focussed poster boys, they deliver everything from food and groceries to medicines and stationery. The idea is to increase frequency of transactions on their platforms and become ubiquitous in the long run.

Swiggy did not respond to an email from Forbes India. Dunzo Chief Executive Kabeer Biswas wrote: “We are largely keeping ‘no comments’ externally for all stories. About time to put our head down and focus.”

Their inspiration to go wide possibly comes from Chinese and Southeast Asian startups. Take for instance, China’s Meituan-Dianping that dabbles in everything from in-store dining and on-demand delivery to hotel reservation and running a programmatic marketing platform. An investor in Swiggy, the firm raised $4.2 billion in a public listing on the Hong Kong bourses last October. Then there is Indonesian startup Go-Jek, a meal and grocery delivery to courier services and bike taxi provider, which has shored up about $3 billion in venture capital (VC), valued at approximately $10 billion. Kabeer Biswas, Dunzo chief executive

Kabeer Biswas, Dunzo chief executive

Image: Selvaprakash Lakshmanan for Forbes India“The earlier versions (of hyperlocal) didn’t work because they were trying to build them standalone. Now, Swiggy and Dunzo have a sizeable delivery fleet and peak hours for categories like food, groceries, etc, are different from each other. So you can mitigate delivery costs with volume. In that perspective, a horizontal play can make more sense,” says Ramaswami.

*****

The first wave of hyperlocal startups in the country delivered either food or grocery from neighbourhood stores. They found support in a clutch of bulge bracket investors such as SoftBank, Tiger Global Management, Sequoia Capital, Nexus Venture Partners, Accel Partners, Saif Partners, Bessemer Venture Partners and Norwest Venture Partners.

Such was the euphoria around hyperlocal between 2013 and 2015 that Sequoia Capital, which missed the ecommerce bus, bankrolled two competing businesses—grocery delivery companies Grofers and PepperTap. Accel Partners and Saif Partners bought into both food and grocery delivery. While the former invested in ZopNow (grocery) and Swiggy (food), the latter opted for PepperTap (grocery) and Swiggy.The optimism wasn’t misplaced. Similar startups in the US were at the top of their game. This was a time when Silicon Valley discourse massively swayed sentiments in India, unlike today, when Indian investors and founders largely look up to the Chinese or Southeast Asian markets for validation. Replicating US models here was the norm then.

Consequently, while companies such as Instacart (grocery delivery), DoorDash (food delivery, started piloting groceries last year), Munchery (food delivery, shut shop earlier this year) and Postmates (delivers anything, but big on food) raised boatloads of money, the ripple effect was felt in India as well. Vertical focussed delivery startups were flooded with money.

But the halcyon days were numbered. “First, the market is much larger (in the US). Even if you look at software products there, you take a small problem and solve it really well, rather than go after all problems.

This is the US DNA. Each of these guys get adequate capital to be able to do that. Also, the breadth of the VC market is much wider, unlike India. Hence, a lot of capital has gone into each of these categories,” says Ramaswami.

Capital constraints aside, India turned out to be a different beast altogether. First, the average order value in India was much smaller than in the US, most of the time half in size, say industry observers. Second, the concept of convenience fee, which hovers around $2-10 in the US and largely offsets the cost of delivery, was alien to Indian consumers.  Dunzo morphed into a horizontal on-demand platform much ahead of Swiggy. But the latter’s deep pockets will pose a significant challenge to its expansion plans

Dunzo morphed into a horizontal on-demand platform much ahead of Swiggy. But the latter’s deep pockets will pose a significant challenge to its expansion plans

Image: Madhu Kapparath

The Indian ventures were instead compelled to make do with whatever commission they earned from neighbourhood stores—largely in single digits for grocery and less than 20 percent for food. On top of it, exuberant spends on offers and discounts meant they remained in the red. “India in that way is much more value conscious than the US,” says Karthik Reddy, managing partner at Blume Ventures.

There were other issues to contend with as well. Says Albinder Dhindsa, chief executive and co-founder at Grofers, “One of the main reasons why we moved away (from hyperlocal) to an inventory-led model was because of the supply chain problem.” A Grofers delivery executive ended up hopping multiple stores, as more often than not one neighbourhood store didn’t stock all the items ordered. On several occasions, Grofers failed to deliver all the items. A similar scenario played out at PepperTap.

“When you start passing through a lot of orders in grocery, customer experience takes a beating. When you pick up some orders from one place and the rest from another, cost of delivery increases,” explains Dhindsa. “You don’t really know what the assortment would be at the local level. Eventually the cost of fulfilment becomes high. Customers will still love the service, but to make the economics work becomes a stretch.”

As chinks in their armour became obvious, most startups fell out of favour with investors. Some underwent a course correction to stay afloat—Grofers adopted an inventory-led model, ZopNow shunned grocery to become a software provider to small businesses looking to set up an online presence and Zomato shrunk its workforce to cut costs—while most shut shop.

It seemed as if the hyperlocal bandwagon had hit a dead end.

*****

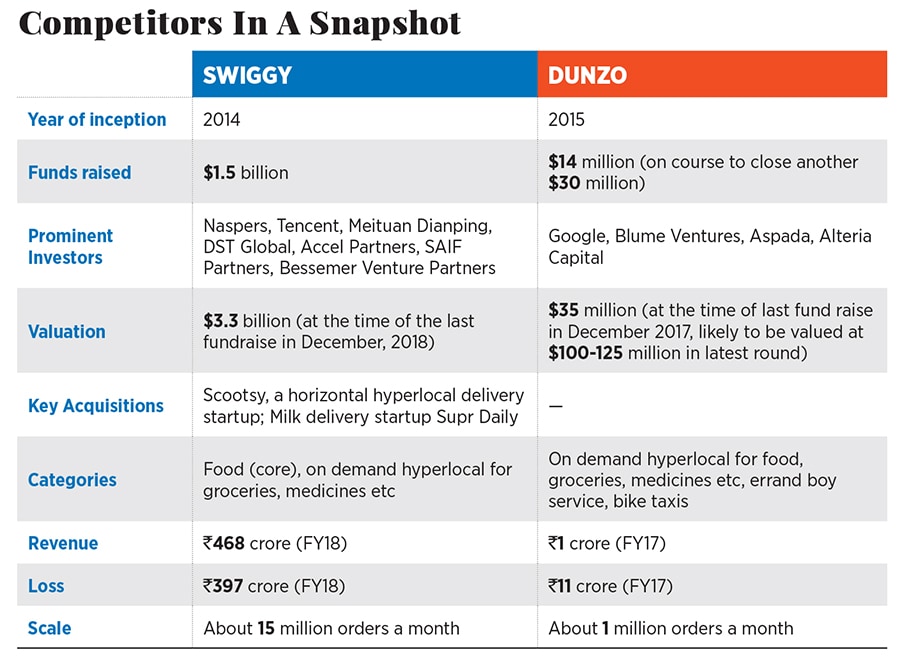

A revival may be on the cards, as Dunzo and Swiggy brace for a land grab. But similarities between Swiggy and Dunzo end with their quest to identify and pursue multiple revenue streams simultaneously. In terms of financial prowess and scale, they are vastly different.

Swiggy, valued at $3.3 billion, is perched atop an approximately $1.5 billion war chest that is certain to be replenished at regular intervals by investors like Naspers, Tencent and Meituan. The firm is estimated to serve at least 15 million food orders every month. Dunzo, on the other hand, has raised a modest $14 million led by Google and is on course to close a $30-million fundraise. The startup serves about a million orders a month.

A massive war chest is crucial for survival as neither of the companies can afford to skimp on offers and discounts. “The market today is still being evangelised by discounting, offers and cashbacks by all platforms to bring on board more and more consumers. But we are in the habit-formation stage. Once the habit is formed, the companies will have more opportunity to monetise consumers. Today, they are mostly monetising the supply side,” says Aakash Goel, partner at Trifecta Capital. In that regard, both Swiggy and Dunzo have started charging a convenience fee for deliveries from some stores.

“Games are being played because you are on a moving chess board where somebody with a billion dollars is playing games too. Dunzo is not building this business in isolation. It was profitable at the unit level before Google first invested, but you can’t play that game because nobody wants you to scale at that pace. Everybody is greedy to see massive scale much faster,” says Reddy.

Dunzo can be safely called India’s first horizontal hyperlocal delivery startup. The firm started as an errand boy service in early 2015, but morphed itself into its current form last year, much ahead of Swiggy’s expansion beyond food delivery in February 2019. While Swiggy had been contemplating a broader hyperlocal play for about a year, its intentions became clear last June, when it bought smaller rival Scootsy, a Mumbai-headquartered startup, for ₹50 crore in an all-cash fire sale.

Cut to chase, Swiggy’s financial muscle could put a spanner in Dunzo’s growth story. As is the case with most consumer internet business, a massive war chest is best fought with another, at least in the formative years of the business. But shoring up capital to fight a well-oiled competitor is a gargantuan task. Dunzo knows a thing or two about that.

“Dunzo has always been disadvantaged by Swiggy’s war chest. It gets the same arguments from investors, ‘I don’t know how hyperlocal will scale’, ‘How horizontal will scale’, ‘The food guys have so much money that they will do us in’,” says Reddy.

Competition from each other isn’t the only demon that Dunzo and Swiggy are fighting. Each of the segments—grocery, food or medicine delivery, which, according to industry observers are the three high frequency use cases for hyperlocals—are heavily contested. For instance, SoftBank-backed Grofers and Alibaba-backed BigBasket are the frontrunners in grocery delivery. Then, there are a whole lot of micro-delivery startups such as MilkBasket and DailyNinja, who thrive on delivering milk, eggs, breakfast essentials or grocery items every morning. In food delivery, Alibaba-backed Zomato is almost catching up with Swiggy. Medicine delivery is another hotly contested area with the likes of 1mg, Pharmeasy and Netmeds among others vying for the top spot.

Will Dunzo survive Swiggy’s incursion and hold fort against the broader competition? Only time will tell. Historically, in consumer internet, the cookie has crumbled in favour of businesses with deep pockets. But history also says a David had triumphed over a Goliath.

First Published: Mar 14, 2019, 10:53

Subscribe Now