Dunzo: Google's chosen one

Internet search giant leads ₹75 crore in Bengaluru-based Dunzo, its first direct investment in a homegrown startup

Kabeer Biswas, founder, Dunzo

Image: Selvaprakash Lakshmanan for Forbes India

Kabeer Biswas, 33, makes a living by saving people’s time. Dunzo, a hyperlocal delivery startup he founded in January 2015, lets users outsource the most mundane of chores—ordering a pack of chips, getting a clock repaired or laundry done—to its army of 1,500-odd bikers at a cost.

At a time when consumers are pampered by free deliveries, offers and discounts, Dunzo—which operates only in Bengaluru, charging at least ₹45 per order—is getting people to pay for about 100,000-120,000 tasks it executes every month, clocking about ₹1 crore in monthly revenues. Repeat purchases per customer for the company have increased from three a month in January 2017 to about five a year later, while delivery time has dropped from 75 minutes to about 45 minutes in the same period.

Consequently, while most hyperlocal startups have fallen out of favour with investors, Google led a $12-million (approximately ₹75 crore) funding round in the company last December, marking the internet behemoth’s first direct investment in a homegrown startup. According to Tracxn, a startup tracker, Google picked up a 31 percent stake in the company against an investment of ₹65 crore.

Biswas is an engineering graduate from Mumbai University and studied management at the Narsee Monjee Institute of Management in the city too. He worked hard at his sales and product management jobs at Airtel between 2007 and 2010, before slogging 14 hours a day to run his own Gurugram-based deals discovery company Hoppr between 2011 and 2014.

His latest venture was borne out of the idle time he had after the sale of Hoppr to Hike Messenger. A resident of Mumbai, Biswas had shifted to Bengaluru and was bored of exploring the city in his rugged Santro for about six months. It was around then that he decided to test a new business idea. “Imagine a product which is a self-completing to-do list. That was my first articulation of it,” Biswas tells Forbes India during an interview in his cabin, a room on the first floor in a duplex at a tony Bengaluru neighbourhood, now Dunzo’s headquarters. “I told this to three of my friends who then spread the word.”

Soon, he was running errands for people on a bike, doing everything from picking up Diet Cokes from a neighbourhood store to getting a grandfather clock repaired, for free. People could drop a message on WhatsApp and the job would be done. He functioned alone for the first couple of months, but as volumes grew, he hired a few people from NGOs on a part-time basis to help him out. Biswas still marvels at the popularity of Dunzo in its earliest avatar. “I have never understood it, but what I hear from people is that this product had a nudge effect. You could sit at a dinner table and tell others about it,” he says.By June 2015, the team at Dunzo was completing about 70 tasks a day. In the next three months, the startup had raised ₹4.4 crore from Blume Ventures, Aspada Investments and angel investors Rajan Anandan and Sandipan Chattopadhyay. Interestingly, some of Dunzo’s early adopters were executives at Aspada Investments and friends of Karthik Reddy, managing partner at venture capital (VC) firm Blume Venture Advisors.

Says Sahil Kini, principal at Aspada Investments, “I heard through referrals that an overqualified, crazy fellow does errands on WhatsApp. We used it [Dunzo] at the firm for a couple of months and this guy [Biswas] kept showing up.” Aspada made an exception to its funding philosophy of participating in Series A rounds and beyond to cut a seed cheque to Dunzo.

This was a time when VC investments in India were at their peak. Hyperlocal delivery startups like Grofers, Swiggy, TinyOwl and PepperTap had raised millions of dollars from the likes of Tiger Global Management, SoftBank, Sequoia Capital, Accel Partners and SAIF Partners. Besides, there were global precedents in the personal assistant segment—such as Magic, Dispatch, Facebook Messenger’s now-defunct M and Zirtual—with reasonable success. In India, startups such as Dunzo, GetMyPeon, Wishup, OK Sir and JoeHukum were starting to take shape as well.

*****

As demand surged, Dunzo migrated from a WhatsApp-based service to an app in February 2016. It acquired artificial intelligence-based concierge platform Wingman to bolster technology. Wingman founders Mukund Jha and Ankur Aggarwal joined Dunzo as co-founders. Besides, Dunzo scaled up its delivery fleet and started partnering with neighbourhood stores to set up a robust local commerce machinery.

In July 2016, Biswas wrote an email to users, regretting Dunzo’s inability to run errands for them for two months. The requests were doubling every week and Biswas was left stranded for want of adequate delivery executives. Dishonesty and opacity, claims Biswas, were struck off from Dunzo’s playbook at the outset. “We are honest as a brand. We will tell you what has happened. I front tasks and have been at the receiving end of an angry user. But the only thing that works in the long run is honesty,” he says.

Aspada’s Kini concurs. “We haven’t seen this customer-centric mindset in anybody. Despite doing someone else’s work, Kabeer has empathy for the consumer. For instance, Dunzo will allow you to place a new order midway into an existing task. This malleability, that we will adjust for you, the consumer, is a very Indian thing,” he says.

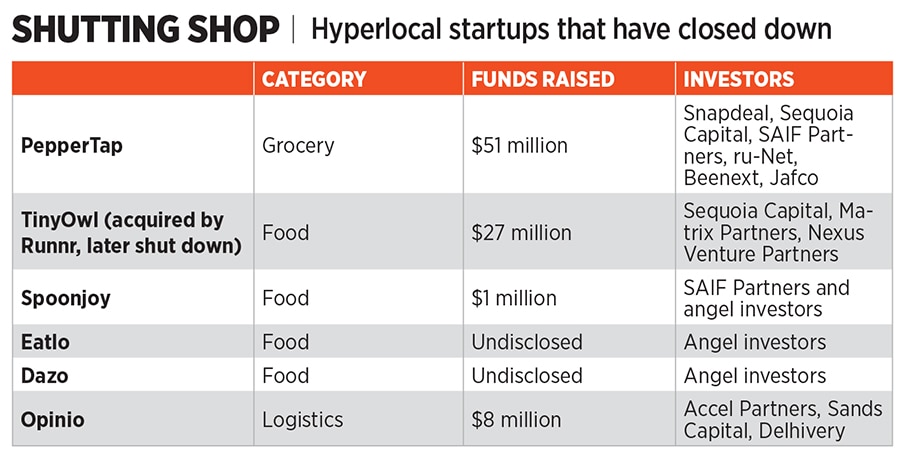

The road to obtaining funds for Dunzo was full of hurdles. The bumpy ride was expected amid a slowdown in funding and cases of hyperlocal startups having shut shop (see box). Riddled with poor unit economics, where they ended up losing money on every order delivered, hyperlocal startups, especially in the food and grocery delivery space, had no option but to fold up or pivot (like Grofers that switched from being a marketplace to an inventory-led model).Having been on a fundraise trail since March 2017, all Biswas had by September were a couple of offers for a buyout. “We tried raising money from almost everybody in this country, but nobody gave me any,” recalls Biswas. His nine-month quest ended with Google. The internet search giant was then strengthening its Next Billion Users programme in India, essentially evangelising an array of products and services targeted at promoting internet usage among the yet-untapped populace in emerging countries. Dunzo’s hyperlocal model seemed like the right fit.

“If you were to think of local search in a world where everything actually gets delivered to you, Dunzo would be the product that one builds. We are building a highly available logistics layer in the city that allows for everything that a user thinks off to actually be in their hands. The deep product thinking at Google has always made the conversation with them much more valuable,” says Biswas.

Last April, Google launched its own hyperlocal app, Areo, in India. “They are trying to understand the actual underlying commerce that happens in localised markets and the only way to know that is to get deeply embedded in hyperlocal,” says a person privy to Google’s plan.

In December 2017, Dunzo was valued at ₹209.6 crore. Apart from Google, Aspada has a 22 percent stake, Blume Ventures 12.4 percent while Biswas holds a 15.1 percent stake in the company, according to Tracxn.

*****

There are no free deliveries at Dunzo. And, unlike peers, who are trying to capture one vertical at a time, Dunzo wants to become a horizontal platform for three types of services: Pick up and drop (collect a product from point A and courier it to point B), purchase (anything from an iPhone to food) and repairs and transactions (picking up a product, getting it repaired and returning it to its owner or doing rounds at a laundry).

Biswas believes dabbling in multiple verticals will help Dunzo utilise its fleet of delivery executives optimally. The company is exploring the launch of bike taxis in the months to come.

The startup also constantly analyses the performance of its verticals and has shut down three—home services, secretarial jobs such as booking movie tickets or placing an order on an ecommerce site and tasks involving the government, for instance, getting a PAN card, etc—even if it impacts traffic. “Just because it is traffic for us, it does not mean that we are not looking at five years hence. Most of them have low frequencies. The one big learning is that you becoming a fire hose to others is not really a business, at least not in the long term,” says Biswas.

Dunzo has a stronghold over pick-up and drops and repairs and transactions, but staving off the likes of Zomato and Swiggy in food or BigBasket and Grofers in grocery will be an uphill task.

They not only have a well-oiled delivery fleet, but also the financial muscle to draw consumers with offers and discounts. Having said that, nothing stops Dunzo from taking the same path and charge businesses a fee instead of taking it from consumers. Else, it could partner with its well-funded peers in food and grocery delivery to aggregate demand for them.

“In that case, Dunzo can either have two sides of the revenue or give up revenue on the customer side. We keep having these debates. Some founders are paranoid, but Kabeer is collaborative that way,” says Reddy of Blume Ventures. “He [Kabeer] wants to build a business that is sustainable with the ecosystem rather than go heads up with no reason at all. All such decisions depend on how each vertical plays out. That said, will Dunzo do it for 10 other verticals? No. This is probably for food and grocery.”

Despite the challenges, Biswas’s confidence in Dunzo remains intact. After all, a similar business such as Go Jek, also backed by Google, has flourished in Indonesia. Besides, internal metrics at Dunzo have improved. “Products today have to think of hyper convenience. Convenience isn’t enough. And users are today willing to pay a small premium to save time for themselves,” says Biswas.

First Published: Feb 22, 2018, 12:37

Subscribe Now