Solving for India: Five startups tackling social problems

These ventures aim to make money by tackling some of India's biggest social problems

In popular imagination, India’s startup ecosystem is synonymous with the posh software firms of Bengaluru, Pune and Gurgaon. While these have made the country a global powerhouse, their appeal eludes two-thirds of its population that are fighting for access to basic needs like clean toilets, good schools and hospitals. This is where a new clutch of companies have come up in recent years. These ventures are laying the groundwork for tapping these needs as business opportunities they are not dependent on charity or grants, but on the citizens at the middle and the bottom of the pyramid to sustain them as paying customers. “The raison d’etre for all these companies is market failure at the mid- to low-income levels,” says Srikrishna Ramamoorthy, a partner at Unitus Seed Fund. “The entrepreneurs we fund are always asking ‘how can I make this scalable so I can make money because of the volume’.” Here’s a look at five such companies.

Hippocampus Learning Centres

Vertical: Early childhood education

Founded: 2010

Business model: Fees from schools, ranging from Rs 3,000-Rs 7,000 per child per year

Investors include: Asian Development Bank, Unitus Seed Fund, Khosla Impact

Funds raised: Rs 21 crore

Impact: 11,000 children getting structured pre-school education from 600 teachers in 285 schools

Status: Seeking between $4 million to $6 million in VC funding to expand and break even in the next 12 months Image: Rakesh Sahai

Image: Rakesh Sahai

Umesh Malhotra’s experience of building libraries for poor kids exposed him to the lopsided education system in the country

When Umesh Malhotra, 47, started Hippocampus Learning Centres five years ago, the idea was simple: Ensure that the poor get a headstart. The plan was to build and run an organisation that goes into villages and operates pre-schools (three years of schooling before class 1). “These three years of intervention empowers the children to face grade 1, where requirements are fairly stiff,” he tells Forbes India.

From 2011, when the first schools were started, Hippocampus has today expanded to 285 locations, predominantly in Karnataka, and includes 12 schools in neighbouring Maharashtra as well. These centres account for about 600 full-time teachers teaching 11,000 children five-and-a-half days a week. The company also has an 80-member staff to run operations like teacher training, meeting parents, getting feedback, enrolling children, collecting fees and running the backend IT systems. Hippocampus pays the salaries of the teachers from the school fees it collects. The fees range from Rs 3,000 to Rs 7,000 a child per year, depending on the size of the village and its economics. (The fees can be low as the programme is designed to keep costs down.)

Malhotra started his career as one of Infosys’s early employees, with an engineering degree from IIT-Madras he worked at the IT major for nine years leading up to its listing on the Nasdaq stock exchange in 1999. He then quit to start his own IT company called Bangalore Labs, which he sold to IT services company Planet One Asia in 2002 and gravitated towards education thereafter. For the next five to six years, he focussed on building good libraries for children from low-income households. “The experience that the children were having, the joy of books… it all seemed to be a lot more fun than the IT stuff,” he says. “This was more real life and experiential.” The effort evolved into an “open source” model in which anybody could take his detailed set of prescriptions and how-to instructions and build libraries.

This experience exposed him to the education system in the country and, in 2010, he decided to enter the turbulence of that world. An early deliberate decision was to identify villages that had a “very, very long shot at being influenced” and, in 2011, Hippocampus started in the villages in Davangere and Mandya districts of Karnataka. Teachers were recruited and trained locally on a centralised curriculum.

Malhotra also had to ensure that enough families—typically villages of at least 3,000 to 5,000 people—would be interested and could afford the basic fees. The typical household income of such families would be about Rs 60,000 annually.

Today, the schools get a tablet with internet access they also have software applications that track data about attendance, enrollment, collection of fees, student performance and rating of the teachers across villages. Parent-teacher meetings are conducted thrice a year and feedback is collected and sent back to Bengaluru.

Building Hippocampus as a for-profit also made it possible to attract venture capital funding of about Rs 21 crore, including Rs 14.4 crore in mid-2014, its biggest round to date. The funds are intended to strengthen the company’s operations, fortify its technology and expand its centres. The startup would break even at 20,000 students, Malhotra says, and that is just a year away. That is when the revenue, currently at approximately Rs 5 crore, will almost double.

Vertical: On-demand digital services

Founded: 2012

Business Model: Revenue from serving global clients in technology, financial information, and internet retail

Investors include: Omidyar Network, Michael and Susan Dell Foundation, Khosla Impact

Funds raised: About $5 million

Impact: In the process of expanding from close to 600 employees (emphasis on young women) from low-income households to 6,000 in 15 centres by 2020

Status: Operationally profitable, investing back into technology and expansion

Radha Ramaswami Basu decided to focus on young adults, but used a different approach. The 65-year-old Basu, a former general manager at Hewlett-Packard’s $1.2 billion channels business who also started the MNC’s India operations, saw an opportunity to skill thousands of Indian youth, especially women, from very low-income households, to serve in the digital economy.

Based in Kolkata, iMerit provides tech-enabled services—digital as opposed to the call centre kind—to global companies from centres in eastern India. “I have fundamentally one belief: That is in the power of youth and young women, particularly rural, marginalised and minority folks,” co-founder and CEO Basu says.

She shuttles between San Francisco, California and Kolkata, and is also the Regis McKenna Professor of Frugal Innovation at Santa Clara University. iMerit has a sales-facing office not far from Palo Alto. Basu points out that while, in the last 20 years, the IT industry has created well-paying jobs for young engineers from the Indian urban middle class, “it has, at the same time, created or even widened” the divide between those who have prospered and those who have been left behind.

Ask any Nasscom company if they’d hire an underprivileged person, the answer is likely to be “well, they don’t have engineering degrees” or even a college degree, she says. iMerit wants to prove that, given the right training, even these young women, who aren’t fluent in English and have, at best, managed to clear class 12, do exceptionally well. “The vision is to see how we can create a model that taps into the massive digital transformation that is going on all over the world, and have these young people coming from very low-income households become part of that transformed economy.”

In October 2015, iMerit raised $3.5 million in its second round of funding from Michael & Susan Dell Foundation and Khosla Impact Omidyar had previously given iMerit close to $1 million in the startup’s first major round of funding in March 2013. These funds will be used to expand from six centres and about 600 employees to 15 centres and 6,000 people over five years. iMerit, however, declined to provide any revenue details.

From verifying driver documents for Uber to validating information on hotels and travel sites to categorising data and images for online shopping sites, the iMerit staff learn to handle a myriad set of tasks. The company is able to do this through a combination of automation as well through its employees who are trained to use new technologies and software on a sophisticated platform built by iMerit—one that matches client requirements with specific job skills. “The nexus of machine intelligence and human intelligence will be the future of work,” Basu says.

iMerit finds most of its staff from among the poor youth in the country. The training is delivered over several months at Anudip Foundation for Social Welfare, which Dipak Basu, Radha’s husband, co-founded with her in 2007. Thus far, Anudip has trained some 45,000 marginalised youth, helping them get jobs in mainstream IT-enabled services companies, including iMerit. Clients such as Microsoft Corp, eBay Inc and Catholic Relief Services use iMerit for projects including machine learning, mobile and cloud support, and big data analytics.

iMerit has also succeeded in building training programmes that help their employees handle tasks such as “sentiment analysis around Twitter images or YouTube or categorising news and graphics”, says Basu. Sentiment analytics refers to extracting information from studying data from sources like social media feeds, and is increasingly being used in marketing and customer services.

“India can be the laboratory where this [kind of workforce] can be created for all the emerging markets,” she says.

Vertical: Biomedical devices

Founded: 2010

Business model: Revenue from sale of biomedical products, and from recurring subscription for cloud-based technology platform for remote diagnosis

Investors include: IDG Ventures, Accel Partners, Asian Health Fund

Impact: Retinal eye imaging device benefitted 2 million people in 25 countries, bringing affordable early detection of preventable blindness to places with low access to healthcare

Funds raised: $13 million

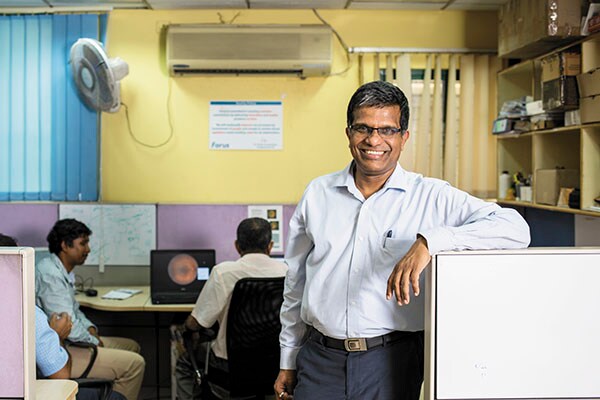

Status: Expanding into new products projected to be profitable in the current fiscal year Image: Vivek Muthuramalingam for Forbes India

Image: Vivek Muthuramalingam for Forbes India

A talk on preventable blindness during his stint with Philips compelled K Chandrasekhar to quit his job and look for solutions

K Chandrasekhar has built a business around an innovative product to improve early detection of preventable blindness. The effort started in Bengaluru, but has now benefited people in 25 countries and counting.

Chandrasekhar says he first heard about preventable blindness when a specialist from the Aravind Eye Hospital chain visited Philips India, where he was director of strategy for the company’s semiconductor unit (NXP Semiconductors). The visit was part of an event titled ‘India Business Incubation’ that brought together experienced people from different walks of life to talk about their work. That talk, in 2005, on preventable blindness stayed with Chandrasekhar and, four years later, he was ready to quit his job and do something about it. He decided to build a simple, portable eye scanner and Forus Health was started in January 2010.

Later that year, Shyam Vasudev, who was Chandrasekhar’s friend and colleague at Philips India, also joined him as co-founder. Vasudev had been the technical director for the health care unit at Philips India, and the collective yet diverse experience proved critical. Vasudev is also a gold medallist in embedded systems engineering from the Indian Institute of Science, Bengaluru, and Chandrasekhar is a graduate of the global manager programme at IIM-Kolkata.

“In addition to the financial and economic impact of blindness, we also understood the emotional impact, how a person’s own family treats him or her as a liability,” Chandrasekhar tells Forbes India. He went deeper into the subject, started going to the Aravind hospitals, and discovered there were about 20,000 ophthalmologists in India for a country of a billion people. That is almost like one ophthalmologist for every 60,000 to 65,000 people and even then, most of them would only be found in the cities. “So villages will be really deprived.”

He couldn’t do much about the number of doctors, but with his deep knowledge as an engineer, Chandrasekhar realised he could build something that would help preventive screening. “Eradicating preventable blindness is the mission,” he says of Forus Health, and the medical devices he built were more a consequence.

Forus has also managed to crack an important problem—to get people to accept and use the product. Initially, they did this by demonstrating their retinal screener: It worked well, and cost far less than imported scanners aimed at large hospitals. From the very first model the company built, called 3Nethra, the screener was portable enough for a pillion rider on a bike to carry it. So it could be taken from vi llage to village.

Second, the device was easy enough for a class 10 graduate to operate. The images from the screener can be sent to an ophthalmologist in a digital format for viewing on his or her smartphone. From 2011, when the first commercial model was launched in the Indian market, the screener has seen iterations, with improvements and additional features being added and multiple models created.

Forus raised $5 million in 2012 from IDG Ventures and Accel Partners, and another $8 million the following year, with both investors participating in addition to the Asia Health Fund. The money helped the company start building a more comprehensive set of technology applications—both software and medical devices—that is now ready to function as a cloud computing-based remote medical diagnosis platform. The platform will also function as a service and could accelerate its revenue growth in the coming years.

The eye-imaging device sells for between Rs 5 lakh and Rs 6 lakh Forus also has another revenue stream from the recurring annual subscription—in the range of Rs 20,000-25,000 per year per device—that the health care providers pay for its cloud-based software and storage for the purposes of remote diagnosis. The privately-held company declined to comment on revenues, but is on track to becoming profitable in the current fiscal that ends March 2017.

The eye scanner itself has been installed in 1,100 hospitals as well as diagnostics labs, diabetics treatment clinics—as diabetes-related blindness is an important factor—and the Aravind Eye Hospitals. The screener is now used in 25 countries and around two million people have benefited from its use.

Vertical: Biomedical equipment and device as a service

Founded: 2009

Business model: Revenue on a per-scan basis by various public and private health care providers

Investors include: Unitus Seed Fund, Aarin Capital, Pennsylvania Department of Health, University City Science Center

Funds raised: About $4.1 million

Impact: Affordable early detection of breast lesions at Rs 80-250 a scan

Status: Setting up manufacturing and distribution in India projected to break even by Q32017

Non-invasive scanning at affordable rates for the masses is also the vision behind iBreastExam, offered by UE LifeSciences. The company has built and commercialised an ultra-portable scanner that pairs up with a smartphone and local health workers can be trained to use them. A scan can be as inexpensive as Rs 80 to Rs 250 compared to as much as Rs 2,000 for a mammogram in a private hospital, co-founder Mihir Shah says.

iBreastExam, however, also represents a more modern and discomfort-free alternative, he says. With bases in Philadelphia and Mumbai, UE LifeSciences won $3 million in funding from Unitus Seed Fund and Aarin Capital, and is now setting up local manufacturing in India.

It all started with a personal motivation for Shah, 38. When a family member of his was diagnosed with breast cancer, he realised that “we don’t have enough radiologists nor have the women and their families the ability to pay for expensive mammograms”.

Shah, who sees himself as a mobile-health entrepreneur, was an executive at Philadelphia-based company Infrascan, another medical devices startup, before starting iBreastExam. His engineering background—a graduate’s degree from Drexel University in the US—helped him think through the plan. “We didn’t know what kind of machine we would design when we started, but we knew that the core desire was to solve this problem of affordable and effective early detection.”

Shah co-founded his company in Philadelphia with Mathew Campisi, who is the company’s CTO. They wanted to start operations in India and build a replicable model, which would then help Shah expand into other markets—South-East Asia, the Middle East, Latin America and Africa—where there is a similar need to help large numbers of women. That India has the largest number of English-speaking physicians in one single market was significant. More women die due to breast cancer in India than anywhere in the world, Shah says. “I have roots in India. If you can help solve the problem here, then you can solve it elsewhere.”

Shah has a degree in computer science, but his fascination and journey with biomedical devices started when he won a business plan competition, which got him an incubation space that was co-located with the university’s technology commercialisation office. This allowed him interactions with the engineers and scientists there.

When he discovered that the biomedical engineering department had developed a non-invasive way to measure some of the health parameters of the human heart, he convinced them to lend it to him over a summer vacation to try it out in India. “My hook was, in less than a week of being in Mumbai, I was able to get appointments with some of the leading cardiologists of the city.”

Those meetings led to invitations to their operation theatres and over the next eight weeks, Shah got a ringside view of various kinds of heart surgeries. “The doctors embraced the non-invasive box, which was inherently harmless, without any kind of red tape,” Shah recalls. “That taught me that ‘non-invasive’ is good. I went back with 60 cases of people suffering with various heart problems in my hand, and the university was able to licence the technology to an established medical device company in the US.”

His second big realisation was that innovation can significantly improve upon what is available in emerging markets. Third was the sheer scale of the disease: Cancer affecting more people who don’t have the wherewithal to deal with it.

Shah went ahead “on a gut feel” and licensed the technology and some related patents from Drexel University, but didn’t really have the money to develop it further. Around that time, in 2012, the Pennsylvania department of health had announced a request for proposals in the area of cancer detection, offering something just shy of $1 million to six finalists to develop solutions with the intent to commercialise.

UE LifeSciences won a place in that list of finalists, and got around $875,000, which helped develop the iBreastExam device from the point where the university had created the proof of concept. The startup put together engineers, scientists, products and industrial design specialists and built the first model over the next three years.

In 2009, the company started out with a larger product, which they called NoTouch BreastScan, which was more amenable to installations in large hospitals and clinics. Cumulatively, UE LifeSciences has sold about $1.5 million worth of these devices at about $60,000 each. However, the portable version, now being commercialised, is the company’s flagship and central to its future.

UE LifeSciences gives out the devices to its customers and charges a fee of Rs 80-Rs 250 per scan. Customers include SRL Diagnostics, Portea, Medall and Metropolis Labs, who will then charge a fee—in the range of Rs 500-Rs 1,000—to the end consumers, Shah says.

The company is also in talks with non-profit foundations including Biocon Foundation, Empathy Foundation, Aastha Breast Cancer Support Group and NK Dhabhar Cancer Foundation to make iBreastExam available to poor people at very low- to no cost. The company has made presentations to the health authorities in the states of Delhi, Rajasthan and Andhra Pradesh as well, Shah says.

Mera Gao Power

Vertical: Energy—setting up solar-powered micro-grids

Founded: 2010

Business model: Tariff charged for off-grid solar power supply at Rs 30 per week per customer-household (MGP sets up the solar units and maintains them)

Investors include: Insitor Impact Fund, Engie and Interchurch Cooperative for Development Cooperation (Icco) with seed funding from USAID and support from National Geographic

Funds raised: About $3 million

Impact: 1.25 lakh people from 22,000 customer-households in 1,500 villages across eight districts in UP get night-time lighting and mobile charging

Status: Seeking $3 million in VC funding to expand operations projected to be Ebitda positive in 2017 and profitable in 2018

Nikhil Jaisinghani, Sandeep Pandey and Brian Shaad have provided electricity to villagers who can’t even afford to pay Rs 180-a-month to state utilitiesAccess to education or better health care improves only with income levels. Mera Gao Power, a startup founded by Nikhil Jaisinghani and Brian Shaad (both 41), solves this problem by providing night-time lighting as well as mobile phone charging to poor households.

Jaisinghani and Shaad had earlier attempted a startup in Nigeria to capture flared gas and provide it to low-income households, but the first-time entrepreneurs realised it wasn’t viable. This attempt was part of Value Development Initiatives, also a for-profit focussed on development through tech innovations that Shaad, a London School of Economics postgraduate, started in mid-2007 and which Jaisinghani joined the following year.

Jaisinghani, who had worked for the USAID, moved to India in 2009, where the idea of lighting as a service took shape. Ten years prior to that, Jaisinghani had lived in rural Nepal as part of a volunteering stint with the Peace Corps, and knew first-hand the importance of lighting for people—he had lived with a family which used kerosene lamps as the main source of lighting.

The duo built their first micro-grid in August 2010, and called their company Mera Gao Power (MGP). They built another in December. They used these as a pilot to understand the technology that would work best in the villages in northern India and also to get a sense of the customers—the village folks who would be using these grids. At the outset, they noticed this: The moment the grids were set up, people started plugging in whatever appliances they had, and one grid shut down on the very first day. They also had to contend with faulty equipment and vendors who didn’t honour their warranty obligations. “We were just a couple of Americans running around in India,” Jaisinghani recalls. Today, they serve 1.25 lakh people from 22,000 customer-households in 1,500 villages in eight different districts of Uttar Pradesh. They have won awards from organisations including the World Economic Forum.

The product was tailored to suit India’s better stature (relative to Nepal) in terms of incomes and also the prevalence of mobile phones by 2010. That led them to design a modified version of the micro-grid, which in addition to providing lighting, allowed users to charge their mobile phones. This was towards the end of 2011, by which time they had been given $300,000 in funding by USAID they rolled out close to 100 micro-grids in the following year, during which Sandeep Pandey, an experienced microfinance hand, also joined as the company’s third co-founder.

This led to the influx of commercial funding in 2013, which has helped them scale up. Insitor Seed Fund made the first commercial investment into MGP in 2013 and made further investments in 2014.

The micro-grids are also unique in that the technology that goes into them has made them cost-effective. Each grid costs Rs 55,000 and can serve a community of 50 households. The systems turn themselves on and customers get two lights and a phone charger for Rs 30 every week.

MGP collects the fees in a system that is similar to microfinance organisations. A collector-agent has an app either on a smartphone or on a tablet, with a list of all the customers in each village and their dues, etc. Every payment is recorded, and customers who have phones sent a text. Branch offices are located at larger “cross-road” towns where MGP can rent an office and store batteries. The collector-agents turn over the money collected that day and sync the data on their hand-held device with MGP’s central computer. “Our target market is very poor. If you look at our branch offices, they are in towns oftentimes located at the intersection of two paved roads villages are located along one paved road and hamlets are usually 3-5 km in,” says Jaisinghani.

In their target hamlets, with as few as 25 households, some can’t afford even the subsidised Rs 180-a-month grid power from the state run utilities. “We’ve been able to figure out a price point that is affordable to them and also competitive with kerosene, which is also heavily subsidised by the government.”

First Published: Jul 05, 2016, 06:12

Subscribe Now