Saama Capital: Not swayed by seasonal flavours

The VC fund has enjoyed a successful ride by backing companies that have the potential to deliver returns

Ash Lilani says Saama Capital loves being contrarian

Image: Nishant Ratnakar for Forbes IndiaWe have seen this movie,” says Ash Lilani, referring to the ebb and flow of venture investments in India, notoriously starved of profitable exits. Lilani, 51, managing partner at venture capital fund Saama Capital, has witnessed the euphoria around Indian startups at the turn of the decade, and the consequent flush of funds. He was also a spectator to the days of frothy valuations, and then watched investors retreat as their bets soured.

The “movie” that Lilani has seen, however, was on a bigger screen, and with more blood spilt: The dotcom bubble and bust of the 1990s, during his stint at the US-headquartered Silicon Valley Bank, a prolific backer of startups. It was in the early 2000s when internet startups such as Pets.com, Webvan and Kozmo rode the tiger briefly, before turning turtle, and lost boatloads of investor money.

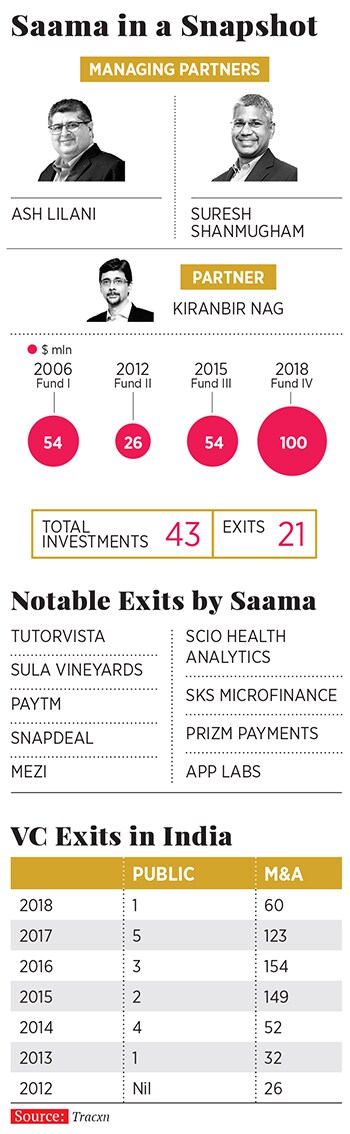

Back in present-day India, Saama Capital, led by Lilani and Suresh Shanmugham, former partner at Boston Millennia Partners, has bucked the trend of unprofitable and scarce exits. Floated in 2006 as SVB Capital India—it was renamed Saama Capital in 2012—the firm has an enviable track record. Out of 43 investments, Saama has exited 21. Fourteen of them have been profitable exits, a couple shut down, while the fund recovered between a quarter-and-half of the capital deployed in the rest. Saama made a windfall by exiting the likes of Paytm, Snapdeal, Mezi, Scio Health Analytics, AppLabs, TutorVista, Sula Vineyards, Shubham Housing, Prizm Payments, Shriram EPC and SKS Microfinance among others.

While Lilani doesn’t bat an eyelid before backing companies he believes have the potential to deliver returns, he is mindful of not getting swayed by flavours of the season. For instance, Saama, unlike its peers, has shied away from investing in some of the hottest sectors of yesteryears, such as food technology and hyperlocal delivery services. Instead, it went whole hog after consumer product companies, bankrolling the likes of Raw Pressery, Veeba Foods, Moms Company, Chai Point, Goa Brewing Co, Genesis and Sula Vineyards.

“We are disciplined, and we do not like conflicts,” Lilani tells Forbes India. “People today say they are ‘founders first’. We have been practicing this forever.”

Paytm’s Vijay Shekhar Sharma should testify.

Lilani’s maiden meeting with Sharma—he was running One97 Communications, a mobile value-added services company, when they first met in 2007—was the antithesis of conventional investor pitches that are held in swanky boardrooms, replete with immaculately designed business projections and jargon.

“The meeting was supposed to happen at his [Sharma’s] office in Delhi’s Nehru Place. He had another urgent meeting to attend, and asked if we (Lilani was accompanied by colleague Kiranbir Nag) could go in his car,” recalls Lilani. Always respectful of an entrepreneur’s travails, Lilani obliged. It was a ride to remember.

“It was the craziest meeting we ever had,” says Lilani. “Vijay is navigating through this chaotic parking lot. His phone rings, and he is talking to the head of human resources. He hadn’t had lunch, so he pulls out a kaathi-roll from his briefcase. He is doing all this, and then turns to us and says, ‘Okay, tell me more about you guys’.”

Sharma, on his part, shared his dream about building a billion-dollar business leveraging the reach of mobile phones. In Sharma, Lilani spotted an entrepreneur for the long haul: Someone who could think big and multitask overall, someone good enough to hand out a cheque to.

It was slightly more than a million dollars. “Vijay’s vision was the primary logic behind the investment,” says Lilani of his first investment in the firm. Saama Capital sold its stake in One97 Communications, Paytm’s parent company, to Alibaba in early 2017, valuing the firm at about $6 billion. Lilani declined to comment on the returns. Saama approximately made 30-fold returns on its total investment of $3 million, according to reports. It continues to hold a small stake in Paytm Mall, the firm’s online commerce wing.

“It [Saama] has a great track record of finding investments that go really big. It has delivered cash exits, and not just notional up-rounds by virtue of another investor coming in and investing at a higher valuation. The most distinctive feature of Saama is that it times its exits really well,” says Shubhankar Bhattacharya, venture partner at Kae Capital.

Take, for instance, Snapdeal. The online retailer was a crown jewel for its investors for the longest time, before bowing out to Flipkart and Amazon. At its peak, Snapdeal commanded a valuation of $6.5 billion. A pale shadow of its former self, the company was put up for sale last year for a billion dollars. If sold, most of Snapdeal’s investors, especially the likes of SoftBank, Alibaba and Nexus Venture Partners, could end up losing money. But not Saama Capital. Saama sold its stake to Ontario Teachers Pension Fund in late 2015, reportedly valuing the firm at $5.5 billion, snaring approximately 10 times the $4 million it had ploughed into Snapdeal.

With spoils from Paytm and Sanpdeal, Saama ensured stellar returns for its first two funds.

Lilani, again, declines to disclose details of the transaction. “Post the SoftBank round [in 2014], we felt the company was going in a different direction. It wasn’t a venture-backed company anymore, and our value as a venture investor was limited. We are an early-stage investor and would rather spend time with younger companies,” reasons Lilani. “I told Kunal [Bahl, co-founder, Snapdeal] my logic. We have enough respect for what he and Rohit [Bansal] built and wanted to sell in a way that the company wasn’t harmed. At some point you will exit investments, but your relationships should never cease to exist. This has been my philosophy and that has helped Saama a lot,” he says.

It was certainly an opportune exit: While Snapdeal’s valuation peaked a few months after Saama’s exit, its slump began soon after.

Letting go has served Lilani well. “I wouldn’t overplay the timing, but he [Lilani] has some phenomenal exits. And, he is not greedy. He knows what he does. He knows when his contributions are limited. He remains active as long as he believes he can add value. When it is time to move on, he moves on,” says Deepak Shahdadpuri, managing director at venture capital firm DSG Consumer Partners.

At Saama, such exits are a way of life. “Given our relatively small fund sizes, we are not driven by management fees. I believe the only way to create wealth for the team is to ensure that our limited partners make money,” says Lilani.

*****

While one might argue that Saama Capital got lucky, there seems to be a design in these exits. When Lilani says the firm “loves being contrarian and not follow the herd,” it isn’t just hyperbole.

Take fund size, for instance. In April, Saama Capital announced closure of its fourth fund, a $100-million corpus, its largest ever. Its previous three funds add up to $134 million. In comparison, some of the storied venture capital firms in India such as Sequoia Capital, Accel Partners, SAIF Partners and Nexus Venture partners have more than a billion dollars each.Lilani maintains that Saama will never raise a larger fund, and the reason isn’t far to seek. Unlike the US or China, India has mostly been a land of distress sales and share swaps, which have often put venture capital firms in a tight spot. A large fund means more money has to be returned to limited partners, and India hasn’t exactly panned out to be a conducive market for such big bang exits.

“Also, we sell ourselves as a senior-led team. The lead on every deal is an experienced partner and we don’t delegate deals to associates, but at a certain [fund] size, you have to. We don’t want to be a people-heavy firm. I don’t want to do human resources,” says Lilani.

This doesn’t mean the team at Saama is stretched and out of bounds for its portfolio. It is, in fact, quite the opposite, and Lilani is often the quickest to respond in trying times, says Anuj Rakyan, CEO at cold pressed juice maker Raw Pressery.

Rakyan is speaking from experience. Soon after raising about $6 million from Sequoia Capital, DSG Consumer Partners and Saama Capital last October, Rakyan needed more money to buy state-of-the-art high-pressure processing machines. This March, Raw Pressery closed another $10-million funding round, led by Saama Capital.

“Ash led a lot of decision-making in recognising that the company needed capital quickly. He was the first to source new capital options for the company and led the last round. Saama is usually fast in closing deals. There is a certain advantage when you don’t have a large investment committee, and between Ash and Suresh, they have a great understanding and trust,” says Rakyan. “Ash’s greatest quality is his emotional intelligence. And he understands people very quickly.”

Harshvardhan Lunia, CEO of lending startup Lendingkart, agrees. “The caveat here is, Ash knew my brother Anand Lunia, who also runs a fund. He wrote the first cheque of half-a-million dollars based on a telephone conversation, without even meeting me or my co-founder.” That was 2014. This January, Lendingkart raised $87 million in a round led by Fullerton Financial Holdings, and Lilani seems to have hit pay dirt yet again.

Saama is even fine with going slow, if need be, as it did in 2007 and 2011, hardly striking a deal as the firm could not agree on high valuations sought by entrepreneurs. “We are fine with giving the company’s full worth, but not chase them with valuations for the fear of losing out,” says Lilani. “When the downturn happened in 2008, we invested in One97, Scio Health, Sula, TutorVista, etc. Again, when everyone was doing hyperlocal and food tech, we were doing software as a service, fintech and consumer. Now, everybody is talking about consumer products. We have been at it since 2008.”

Lilani doesn’t intend to change much at Saama after the latest fund raise. The firm will continue with early-stage deals, investing $1-3 million in about four companies every year. Only that, from now on, Saama will invest more in follow on rounds and earmark a corpus for what Lilani calls ‘fund returners’.

Saama’s success could either be a function of luck or foresight, or a mix of both. But the founders aren’t complaining, and neither are the limited partners. Venture investment, they say, has a lot to do with luck in general. As Kae Capital’s Bhattacharya puts it, “Had I been a limited partner, I would have sided with that kind of luck any given day.”

First Published: Jun 11, 2018, 15:15

Subscribe Now