Start-up India Action Plan: Glass half-full, yet half-empty

While the Start-up India Action Plan legitimises entrepreneurship, it lacks bold moves that can help young businesses cut through red tape in payments, raising money or listing

It was early this January, a couple of weeks before Prime Minister Narendra Modi announced the coming of age of Indian startups by launching the Start-up India Action Plan in Bengaluru, Anandraj Koormapolu had queued up to get a Rs 500 stamp paper to urgently close a deal.

This was his second attempt in as many days to procure the paper as the vendor in the city’s Koramangala area—home to many technology companies—had closed while he was waiting for his turn the previous day.

Koormapolu, a software products veteran, couldn’t help being bemused at the system he could have spent his time fine-tuning the latest release at his startup. Zoojoo.be, the company he co-founded with friend Avinash Saurabh, had recently raised its first $1 million from venture capital (VC) firm Roundglass Partners, and the two were excited about raising their game. Zoojoo.be brings together employees of an entire company in a social media environment to drive wellness using gaming elements, users are encouraged to set and beat personal fitness goals. The implications of this for health insurance are enormous.

India’s new age startups aren’t about exporting cheap labour. They solve big problems for Indians in India. Some of them might even go on to set the bar for the rest of the world in innovation, despite the frustrating trips for stamp papers and other red tape.

It is the recognition of this potential of the startup economy, and the current environment that stifles its growth, that has prompted the Union government to announce the country’s new policy to build the startup ecosystem.

Everyone Forbes India spoke to agrees the policy is a giant leap forward. “The biggest win here is the government’s recognition of startups,” says Girish Mathrubootham, founder and chief executive of Freshdesk, India’s first startup to attract investment from Google Capital and whose cloud-based customer support products boast of 50,000 customers in 143 countries. “Now we will have a seat at the table,” and startups might get more attention, Mathrubootham said in a phone interview from Chennai.

“The prime minister’s backing for the policy is bringing entrepreneurship to the forefront...making it a household name for the first time in India’s history,” says Alok Goel, managing director at venture capital firm SAIF Partners. “The biggest thing it’s doing is telling people that being an entrepreneur is fine.”

It has also dawned on the government that startups are different from the traditional small and medium enterprises, and that these ventures are a legitimate economic activity and a source of wealth and job creation, says Sanjay Anandaram, partner at Seedfund, a Bengaluru-based VC firm.

For ventures starting today, this is a huge step, says Rajiv Srivatsa, co-founder and chief operating officer at Urban Ladder, which sells furniture online. From creating a Rs 10,000-crore corpus to popularising entrepreneurship in schools, the policy reflects “tremendous energy and momentum”. “Ten years from now... school children will want to do this [entrepreneurship],” he adds.

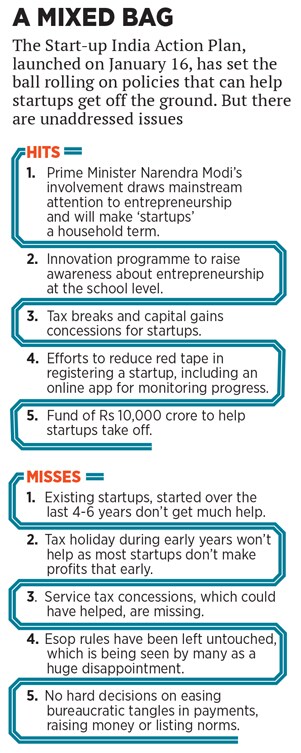

The startup policy also has some tax breaks and other concessions for new startups and tries to make tasks such as registering a new startup, or shutting down a failed one, less bureaucratic. There is even a proposal to build a smartphone app to track the progress of such processes.

While the startup policy has set the ball rolling, there is also the feeling that it lacks bold steps and the new policy is a missed opportunity to have articulated something truly visionary. “I don’t think this policy has anything for startups that were established four years ago or even six or seven years ago,” says Srivatsa, “barring some mentions like encouraging patent filing.”

Aditya Sanghi’s Hotelogix in Bengaluru is a rival to Freshdesk in the hospitality space, selling internet-based customer management software for small- and medium-sized hotels across the world. Sanghi needs to collect payments from customers fairly frequently, “but we can’t have their cards on file”, he says. Under Indian rules, each payment would require a second factor of authentication, which means that startups here can’t save the credit card details of their customers to periodically deduct fees. “I spent a year setting up a unit in the US, which we now use to collect money,” says Sanghi.

With Freshdesk, too, Mathrubootham headquartered the company in the US, which also makes it easier to raise money from overseas investors, and eventually list on a stock exchange. “I understand that the RBI has these rules to ensure security and prevent funding of terrorist activities and such things,” he says. “But you’re also killing startups.”

Bikram Sohal, who started SavvyMob, a last-minute online hotel reservation service, recalled how at an earlier venture, his co-founder had turned up at Hong Kong, where Sohal was based at the time, with a big bundle of documents to register the company. “None of that was in fact required,” Sohal recounts. “Within a few hours we were done, and we had a bank account and a card in a day” and they were good to go. At Bengaluru-based SavvyMob, getting a corporate credit card—for working capital—required a deposit larger than the credit limit as collateral.

“If you can do this [registering a company] in a couple of hours in Hong Kong, and in a day in California, why not here,” Seedfund’s Anandaram asks. “You are forcing companies to leave India because of the onerous documentation requirements.”

The startup policy has made no hard decisions on easing bureaucracy in payments, raising money or listing norms.Another big disappointment across the board is that the policy does not make it easier for startups to use employee stock options (Esops), which are bound by archaic company laws and shackled further by how they are taxed. Employees who have worked, say, five years at a startup, helped it become big, and seen the value of their stock rise manifold in the process will have to pay over a third of the notional value of that stock as tax if they have to truly own the shares, while the company remains privately held.

As a result, many allow the options to lapse, especially when leaving the company to join another. If there’s bad blood between the startup and the employee, that makes the situation worse. There are scenarios when the startup will require signatures on various forms—like the shareholder agreement, for instance—of people who own stock in the company, whether they are current employees or not, says Sanghi. Therefore, Esops are also useless as a way to attract and retain talent, he added. “I’m still struggling to get all my Esops documentation in order. I have just issued promissory notes to everyone.” From starting a company to running it to shutting it, “all the paperwork that’s being asked for today is with an eye of suspicion,” Sanghi says.

These kinds of frustrations—a huge daily distraction from the actual task of inventing something or innovating something—are what compel many firms to move their headquarters to the US, the UK, Hong Kong or Singapore.

Singapore is widely seen as perhaps the best country in terms of ease of doing business, and among the top three least corrupt nations. The city state also has specific regulations encouraging startups. For instance, an inventor can take a working prototype to the government and get financial aid to develop and commercialise it, or, having raised some funding, get matching grants and so on. The inventor in Singapore can also rest easy that the fruits of his labour will not be stolen. In other words, a strong patent regime and a well-developed intellectual property regime is in place.

Not so in India. Goel recalled he had recently met someone who had built a very interesting electric vehicle that had a lot of potential for personal transport, but “he is worried about commercialising it in India because he fears a larger company will copy his idea and bring out a rival product into the market soon.”

Urban Ladder’s Srivatsa agrees: “IP protection takes too much time and is too expensive in India.” So if the government is talking about helping companies on this front, that’s a step forward.

There isn’t much precedence in India in terms of patent enforcement. And in the startup policy, patent enforcement isn’t clearly mentioned. However, there is a discussion on subsidies for patent filing, which implies that there is an interest in creating a stronger patent regime.

While the startup policy is a good start at playing catch-up, there are many areas beyond the immediate purview of the policy that impacts the ecosystem, where there are no quick fixes. These range from basic infrastructure like good roads to 4G networks to what Anandaram calls “invention-oriented research and development”. Take a professor from Stanford University and one from any of India’s top institutes in the same field. “The guy from Stanford will always be thinking, ‘How can I commercialise this?’,” says Anandaram.

“Even in the second or third year of study, if a project is good a Stanford professor will encourage a student to go start a business,” says Sashi Chimala, executive vice president at the Wadhwani Foundation-backed National Entrepreneurship Network. “That culture hasn’t come to India yet.”

This isn’t restricted to the narrow definition of technology. “Show me where in India there is any cutting-edge research in behavioural economics,” says Goel of SAIF Partners. “In the US there is so much of research into cognitive behaviour and how product development must incorporate such findings.”

Startups, both those which copied Western models and adapted them to Indian conditions, and those that are looking to commercialise their own original ideas, can help solve pressing problems and benefit millions of Indians. Enabling them calls for an environment in which being an entrepreneur is a good thing. That, like all good things, starts with the family. “When we were growing up, our parents could only envision us as doctors, engineers or maybe lawyers,” says Goel. “Today a lot of us are open to our children becoming entrepreneurs.”

Koormapolu’s trips to get stamp papers won’t end overnight, but the startup policy is a step closer to that scenario.

First Published: Feb 05, 2016, 06:18

Subscribe Now