Pune: City of Angels

Why Pune might be so close, yet so far, from being India's next big startup capital

Akshay Mehrotra, co-founder, EarlySalary

Akshay Mehrotra, co-founder, EarlySalary

Image: Mexy Xavier[br]Akshay Mehrotra grew up in at least 10 cities across India. The son of an Indian Air Force officer, he studied in places like Agra, Kanpur, Gwalior and Allahabad, while his career took him to metros like Delhi, Bengaluru and Mumbai. Yet, when the 38-year-old decided to quit his corporate career in Mumbai as the chief marketing officer at Big Bazaar (Future Value Retail) in 2015 to launch his own fintech startup, he chose a relatively unconventional location—Pune. Mehrotra is the co-founder and CEO of EarlySalary, a digital lending platform that gives short-term instant credit to customers, to be repaid over the next few days or after the next month’s salary arrives.

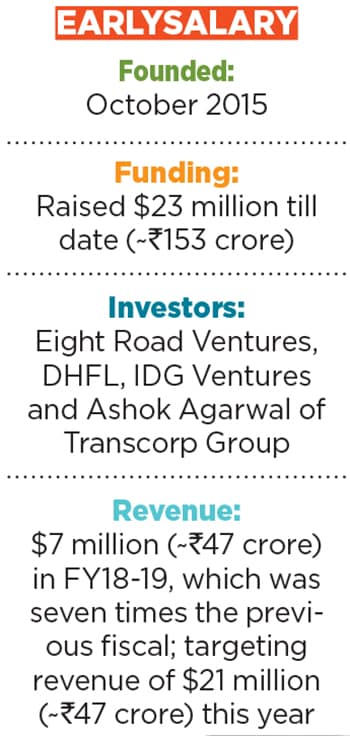

After receiving seed funding of $1.5 million from Ashok Agarwal of the Transcorp Group, Mehrotra and his co-founder Ashish Goyal, both first-time entrepreneurs, gave serious thought to where they wanted to set up shop. “We noticed that, globally, banking tech is built in Pune, not Bengaluru. The big banks [Citibank, Deutsche Bank, Barclays, Credit Suisse] have built development centres here, each employing 5,000 to 15,000 people in their tech teams. So if we want to disrupt banking and hire the right talent, Pune seemed the best place to be,” he says.

Since its launch in 2016, EarlySalary has built a team of over 200 employees, with an 85 percent retention rate. The startup has disbursed 7.5 lakh loans worth ₹1,350 crore till date. Mehrotra claims they have 2.5 lakh paid customers, 90 percent of whom transact repeatedly.

In 2018, it acquired Mumbai-based checkout financing startup CashCare for an undisclosed amount. The same year, Mehrotra and Goyal raised ₹100 crore in a series B funding round led by Eight Road Ventures, the investment arm of Fidelity International, which also saw existing investors Dewan Housing Finance Ltd, IDG Ventures and Ashok Agarwal participate.“On a monthly basis, we contribute almost ₹35 crore to the balance sheet. Our 18-month aspiration is a ₹1,000-crore balance sheet. We will turn profitable in the next three to four months,” Mehrotra says, explaining that the decision to start up in Pune—where he finished his MBA from Symbiosis Institute of Business Management—proved worthwhile. “Being close to Mumbai, we get access to the best financial insights. Operational expenditure is almost 30 percent lower than Bengaluru-based startups. Our employees say Pune offers them a better lifestyle: Low rentals allow them to stay close to the workplace, commute time is less, and the weather is great too.”

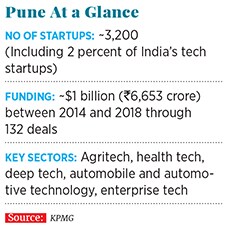

In an October 2018 report titled Rise of the Global Startup City, the Center for American Entrepreneurship called Pune an emerging startup hub in the ‘Global Next’ category. It was the only Indian city on the list, apart from Hyderabad, and featured alongside Columbus, Detroit, Las Vegas, Moscow, Orlando, Cincinnati and Nashville. The report said that this category accounts for less than 1 percent of global venture capital (VC) investments and has the potential to grow.

The report findings are supported by a June 2019 KPMG report titled Pune 2.0: The Startup Hub, which show that Pune received funding worth $1 billion (₹6,653 crore) through 132 deals between 2014 and 2018. The city has close to 3,200 startups, with 2 percent of India’s tech startups based there. Pune is the second highest contributor to Maharashtra’s economy after Mumbai, with an estimated GDP of ₹4.7 trillion. It also constitutes about 11 percent of India’s total IT and ITES exports.

“Pune’s cultural fabric is welcoming to new ideas and people. The presence of numerous educational institutions here provides a talent pool that could be leveraged through more coordination between academia and industry,” says Milind Borate, co-founder of Druva.

The Pune-born data protection company became India’s latest unicorn (a startup valued at more than $1 billion) after it raised $130 million in a funding round led by US-based Viking Global Investors in June. Investors in the startup—which was launched in Pune in 2008 and is also based in California since 2011—include Sequoia Capital, Nexus Venture Partners, Riverwood Capital and Tenaya Capital.

Pune remains the base for Druva’s engineering, research and product development, with over 450 of its 700-strong workforce. Borate says that while the funds will be used to expand operations in Europe and Asia Pacific, they also expect to roll out new products and reach 1,000 employees. The facility in Pune, he adds, will be at the centre of these developments. “The vision is to enable protection and management for all kinds of data.”  Milind Borate, co-founder, Druva[br] Building on Legacy

Milind Borate, co-founder, Druva[br] Building on Legacy

Investors believe that Pune’s legacy as a multi-industry hub, dating back to the early 1960s, has paved the way for startups. Apart from automobiles, the city also has a strong presence of established banking, IT and electronics industries. “Pune is a B2B town. The industry is shifting from providing technology services to developing software products. Startups here could benefit from this,” believes Gireendra Kasmalkar, lead investor and general partner of Alacrity India, one of the first Pune-based VC funds. “Investors are willing to encourage startups that want to solve problems and fulfill needs in their respective industries.”

With a corpus of $10 million, Alacrity India started operations in the second half of 2018, with Canada-based investment management firm Wesley Clover International and Kasmalkar’s Ideas to Impact as lead investors in the fund. It recently made its first investment in Tripeur, a B2B travel-tech AI startup. In February 2019, the company launched an incubation centre to mentor and provide networking opportunities to startups in the city. Gaurav Bansal, principal at Alacrity India, says that the centre provides detailed feedback to entrepreneurs on their business ideas from an investor’s lens. “Stakeholders in the Pune startup ecosystem need to explore local neighbourhoods and develop an integrated ecosystem.”

Kiran Deshpande, president, The Indus Entrepreneurs (TiE) Pune, a nonprofit that has mentored over 100 startups since 2012, says that the Tie Pune Angel has close to 25 members, a number that could rise with angel tax relief. “Following the US, I recommend the government to consider tax rebates for individuals investing in startups,” he says.Entrepreneurs believe that increased mergers and acquisitions in the last two years has also given an impetus to startups. Abhijit Gupta, founder of health tech startup Praxify Technologies, gives examples of how, in 2018, personal finance management startup Walnut was acquired by Capital Float for $30 million (₹2.1 billion), while Big Basket acquired RainCan, a hyperlocal delivery service for fresh and perishable items, for an undisclosed amount. Gupta’s own company was acquired by cloud-based electronic health record company Athenahealth for $63 million in 2017.

“Entrepreneurs who have seen exits recently are turning into angel investors. They are driven by the sense of giving back that will also help them grow,” he says, explaining that the over-exposure and saturation of startups in Bengaluru and Mumbai has resulted in high employee churn and poaching. “Here, employees remain with the same firm for eight to nine years or more. Pune gives people the space to create something ground-up without them jumping from one profile to another in search of the largest pay cheque.”

Building It Right

While Pune-based startups seem to have no trouble retaining talent, many have a tough time finding it. Pune has over 811 colleges, which, experts say, are disconnected from the skill requirements of the industry and mostly provide talent only at entry or junior levels. Other concerns, according to multiple stakeholders, is access to capital, lack of incubators and accelerators.

Shardul Sheth, co-founder of agri-tech firm AgroStar, says, “When you want to scale up, finding senior or experienced talent is a challenge in Pune. Once people come here, they don’t want to move out, but getting people here is not easy.”

Maharashtra Chief Minister Devendra Fadnavis has declared that Pune will displace Bengaluru as the startup capital of the country “within two to three years”, promising “lakhs of job opportunities for the youth”. Entrepreneurs, however, believe that this depends on a number of factors, starting with infrastructure creation.

To begin with, localities with high startup and business activity—Hinjewadi, Baner, Pashan, and Viman Nagar—are in different pockets outlining the city. Construction of a ring road to ease traffic congestion and connect these localities has not yet materialised. Public transport remains an issue. “We keep hearing there will be better infrastructure, but it’s all on paper so far. Hinjewadi, developed as a business hub, is beginning to tell the same story as Whitefield [Bengaluru’s congested IT corridor],” says Gupta of Praxify.

Pune has pinned its hopes on the ongoing metro rail construction—expected to be operational by 2021 and developed at a cost of ₹20,000 crore—and the proposed circular ring road. The construction of an international airport at Purandar has been delayed due to land acquisition issues, while a new terminal is being built at the existing Lohegaon airport.

“To keep up with startup activity, governments must work 10 times faster than their regular pace of infrastructure development. They must put the right energy and effort into this, else the hubs booming now will soon be dead,” Gupta warns.

Vaibhav Domkundwar, founder of Pune-based VC firm Better Capital, agrees with Gupta. According to him, for Pune to rival Bengaluru in the next five years, it is essential to “establish startup hubs with pre-defined infrastructure in different parts of the city and around colleges.” He also calls for a 10x growth in local angel investors and seed funds.To address concerns related to startups, the government had created the Pune Idea Factory Foundation (PIFF) as a subsidiary of the Pune Smart City Development Corporation (PSCDC) in 2017. Rajendra Jagtap, CEO of PSCDC, says they have an annual budget of ₹5 crore for startups under PIFF, which might increase to ₹15 crore as more startups come in. The Pune Municipal Corporation (PMC) provides support in the form of land.

Jagtap’s short-term goal is to create a Centre of Excellence, which will strengthen the existing 19 incubation centres in Pune and provide startups with a space for innovation, networking and mentorship. The PSCDC has collaborated with academic and industrial entities like Nasscom, Google Earth and University of New South Wales in Australia to conceptualise this project. “The focus will be to improve upon the success of startups and help them scale up. We have identified land and are likely to get the physical space by November. Then we will sign the MoU and start building the space,” says Jagtap.

His long-term vision involves creating a digital innovation platform “along the lines of Flipkart and Amazon”, where hackathons could take place 24x7 and companies from across Pune could get in touch with VCs and mentors online. “The PIFF will help create this platform and also evaluate startups on the basis of the criticality of the solutions they are proposing. We will specifically encourage ventures in agriculture, pharmacy, education, automobile and urban environment whose products aid smart city goals,” he says.

The official admits that physical infrastructure is a constraint but ensures that their immediate focus is on completing the metro on time, decongesting city roads, promoting the use of public transport, developing last-mile connectivity and integrated multi-modal transportation.

Pradeep Udhas, office managing partner—west at KPMG, who developed the report on Pune as a startup hub, says that the government must also consider something like the Startup Village in Kochi, which has been developed under a public-private partnership. According to him, while Bengaluru has a more entrepreneurial mindset, people in Pune might still prefer the safer corporate job. “Once they see labs and opportunities coming in, once they see local startups succeeding, their mindset will change. For Pune to become Bengaluru, it’s only a matter of time.”

First Published: Jul 11, 2019, 07:28

Subscribe Now