How North-East India is growing business roots

Entrepreneurs in Assam and Manipur are flourishing with some help from government and private initiatives

Arindam Dasgupta, founder, Tamul Plates

Arindam Dasgupta, founder, Tamul Plates

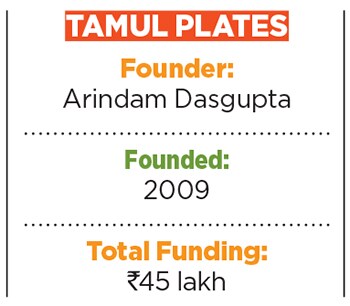

Image: Surajit Sharma for Forbes India[br]About 100 km from Guwahati lies the tiny district of Barpeta, where an unmetalled road wide enough for just one vehicle winds its way through lush greenery. On a 0.3 hectare piece of land there, almost entirely covered with dried areca nut leaves, stands Tamul Plates. Set up in 2010 by Arindam Dasgupta (23), the facility produces 10,000 to 20,000 units of tableware made from areca leaves per day.

Although there are multiple companies in Kerala and Karnataka making tableware from areca nut leaves, Dasgupta was the first to do so in the northeast of the country, making use of the region’s abundant natural resources. The company has received a total funding of ₹45 lakh from Upaya Social Ventures and Rianta Capital, and as Dasgupta says, “is planning to buy 1 hectare land somewhere close by and soon move our production facility there.”

Dasgupta is an example of a new generation of young entrepreneurs who are choosing to set up their fledgling businesses in Assam and Manipur, not just for their abundant natural resources—“We decided to use dried leaf sheaths of areca nut trees to make tableware, but there is so much work being done with bamboo and other resources as well,” he says—but also state government policies, as well as private initiatives.

For instance, Assam has set up an incubation centre, The Nest, in Guwahati along with Indian Institute of Management Calcutta Innovation Park. Pranjal Konwar, COO of The Nest says, “Assam’s startup policy aims to facilitate the growth of about 1,000 new startups, and create direct and indirect employment for 1 lakh people over five years.” There are other incentives under the policy such as GST reimbursements, lease rental subsidies and power subsidies.The Nest has been instrumental in encouraging innovation and technology in the state. Companies such as Zerund (it makes bricks with cement and plastic powder instead of red clay), Little Machines (it makes a portable digital microscope), Lenshood (a photography equipment rental portal) and My3Dselfie (it makes 3D figurines on sandstone) are some of the startups that are now part of The Nest. “When it came to understanding finance and management, the basics of how to run a business, we had no idea. In such cases, the seminars and programmes by The Nest really helped us,” says Ravi Chakravorty of Little Machines.

Apart from government support, there are individuals who are returning to their hometowns to mentor and support entrepreneurship in Assam and Manipur as well. Imphal Angels, set up last November, is a network of angel investors. “We realised that if someone founded a startup here, it would work well for a while and then fizzle out since there was a lack of connectivity with the rest of the world,” says Fisher Laishram, partner, Imphal Angels. “We wanted to do something to give these startups the exposure they need.”The network organised the first ever Northeast Startup Summit in 2019 to help startups from the region understand the nuances of running a business, and create a network of entrepreneurs. Of the 10 selected applicants, the winner received ₹3 lakh funding from the summit. “In the Northeast, any and every other company set up is seen to be a startup. We are trying to redefine this concept, and help people look at startups as companies that are highly scalable and asset-light,” says Chingakham Priyobrata Singh, partner, Imphal Angels.

The Manipur government implemented the Startup Manipur policy in 2016, and provides new enterprises with subsidised loans. It has plans to set up a state-funded incubation centre, offer preferential lease of land, access to government R&D labs, and funding of up to ₹10 lakh to colleges in Manipur to set up Entrepreneurship Development Centres.

Homing in

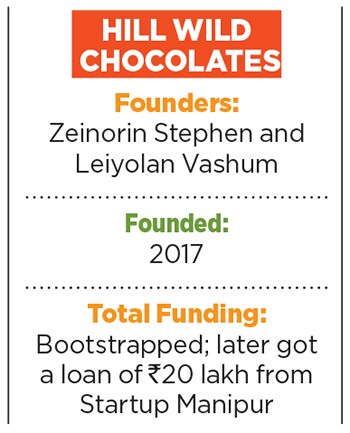

Different entrepreneurs may have different reasons to set up businesses in Assam and Manipur, but the common factor is their wish to develop their home states. (left)Zeinorin Stephen and Leiyolan Vashum co-founder, Hill Wild Chocolates

(left)Zeinorin Stephen and Leiyolan Vashum co-founder, Hill Wild Chocolates

Image: Mongjam Ajitkumar for Forbes India[br]Zeinorin Stephen (26), who earlier worked as a merchandiser in Gurugram, decided to move back to her hometown of Ukhrul, 81 km from Imphal, and join Leiyolan Vashum (35), a local social worker, to set up a chocolate brand, Hill Wild Chocolates. “Growing up, we would find a lot of pumpkin seeds going to waste. We decided to roast them and infuse them into our chocolates and come up with flavours that truly talk about the region,” says Vashum. “We feel a connection with our farmers and community,” says Stephen. “The impact that the brand has on people [by generating employment] is really worth it.” While most of their ingredients are sourced locally, they source cocoa from South India. Launched in November 2017, the brand has flavours such as Pumpkin Seeds, King Chilli, Rum & Raisin, and Wild Apple, and plans to expand to hard boiled candy where most of the sugar will be replaced with natural fruit syrup from pineapples and plums. It is available in the Northeast, Delhi, Pune and Bengaluru and has a turnover of ₹2 crore.

Launched in November 2017, the brand has flavours such as Pumpkin Seeds, King Chilli, Rum & Raisin, and Wild Apple, and plans to expand to hard boiled candy where most of the sugar will be replaced with natural fruit syrup from pineapples and plums. It is available in the Northeast, Delhi, Pune and Bengaluru and has a turnover of ₹2 crore.

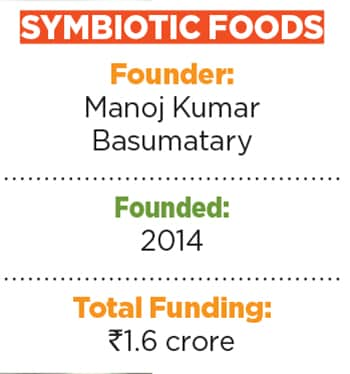

Manoj Kumar Basumatary worked with State Bank of India in Delhi but always wanted to return home to Tezpur in Assam, which he wanted to help develop and where he wanted to generate employment. His research showed that though Assam has India’s highest population of pigs—a source of meat popular in the region—the piggery sector was unorganised and informal. “The sector was not growing because of the poor quality of piglets, and through Symbiotic Foods we decided to change that,” says Basumatary.

The company he established in 2014 in Tezpur sells piglets to farmers and butchers across Assam. It has about 200 breeding units, which produced 2,000 piglets in 2018, and a revenue of over ₹1 crore. Basumatary eventually wants to take over the entire processing chain, from breeding pigs to processing pork and distributing the meat products across the country.

For Dr Parveez Ubed of ERC Eye Care and Dr Dayananda Meetei of Medilane, staying in Assam was a matter of catering to a gap in the market. Although health care and health tech are promising startup spaces today, between 2011 and 2016 the sector was still unorganised in the Northeast.

Ubed (41), who had earlier worked with corporate, government and not-for-profit hospitals, set up ERC Eye Care in 2011 in Jorhat (upper Assam), where most people had to travel 30-35 km to the nearest town, and spend up to ₹2,000 to get their eyes checked and buy a pair of glasses. “Our goal was to make eye care more affordable we charge only ₹50 for consultation. And since my entire team is from the Northeast we understand the people and their expectations better,” says Ubed. ERC Eye Care has received ₹9 crore in funding, including from Ankur Capital, Ennovent (Austria) and Nedfi (Guwahati), and has expanded to four hospitals across Assam.

Meetei had decided on a startup right from when he was a student at Jawaharlal Nehru Institute of Medical Sciences, Imphal. He set up Medilane in 2016 in Imphal, starting with discount cards for patients, and moving to ambulance services, home nursing care and medical equipment rentals the services are available across the Northeast and he hopes to scale to pan-India. Manoj Kumar Basumatary, founder, Symbiotic Foods

Manoj Kumar Basumatary, founder, Symbiotic Foods

Image: Surjit Sharma for Forbes India[br]“There are few competitors here. Also, I feel people here have more disposable income than, say, people in West Bengal. So we are also tapping into medical tourism for people who wish to go out of the state for treatment,” says Meetei. Medilane will soon be launching an app for its services, and is clocking a turnover of ₹20-25 lakh a month. It has received a loan of ₹65 lakh under the Startup Manipur policy.

“I always knew I wanted to get into any form of a startup, but convincing our parents was not easy, because they had not seen anyone in our family run a business,” says Gogoi (23) of Zerund, which has clocked a turnover of ₹32 lakh in the past seven months.

“Factors such as internet penetration, a sizeable English-speaking population and abundance of talent have enabled the region to be established as a hub for entrepreneurs,” says Sangeeta Gupta, senior vice president, Nasscom. “The area continues to be strong when it comes to high quality educational institutions that are encouraging the growth and development of individuals as well as promoting innovation and the emergence of enterprises.”

On-ground challenges

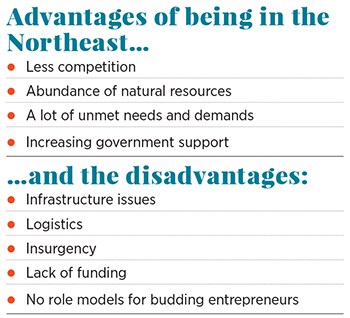

Although the startup sector in the region seems to have gathered pace in the past four to five years, entrepreneurs remain cautious about taking risks, raising funds, and expanding because of several issues that plague the region.

For instance, since Tamul Plates sources its areca nut leaves from Bodoland districts, local disruptions directly affect its business. “In 2011-12, there was a major communal clash and the region was basically shut down for six months,” recalls Dasgupta. “We had to shut down our plant completely.” To avoid a repeat, he now sources raw materials from other regions as well.

Transport and road connectivity are another roadblock. “Although things are slightly better now, we have had to set up a fundraiser to make our own road, to improve connectivity between Ukhrul and Imphal,” says Stephen. Till a few years ago, Dasgupta’s firm had to put up with severe flooding during the monsoons, and it would be impossible to transport raw materials or finished goods. “Our revenue was directly hit due to low productivity,” he says. Both companies wish to sell via mainstream ecommerce channels such as Amazon and Flipkart to tap newer markets, but are waiting for logistics to improve. Power cuts, too, have been an issue, and though there has been some improvement in electric supply and digital connectivity in recent times, remote parts of the Northeast continue to face power cuts.

Besides logistics and infrastructure, other stumbling blocks are the lack of role models and funding. “When I started in 2011, there was limited advice or knowledge available for setting up companies or even making a proper business plan,” recalls Ubed of ERC Eye Care. “I remember typing in ‘angel investment’ in Google to find out what it meant.”

“People here have always looked at businesses very negatively, which is why we lack role models,” says Basumatary. “We are being monitored closely to see if we succeed or fail. If we fail, the younger generation will get no family support in setting up their own enterprises.” Talking about his struggle to find funding for his business, he says, “No one was willing to help me, and even banks refused loans. Finally Netherlands-based ICCO Cooperation agreed to fund us. After that we managed to get a round of funding from Nedfi.” He has received a total funding of ₹1.6 crore.

The North Eastern Development Finance Corporation (Nedfi) set up the North East Venture Fund in association with the Ministry of Development of North Eastern Region in 2017 to fund startups. “It aims to invest in early stage and growth stage startups, with funds ranging from ₹25 lakh to ₹10 crore,” says Paul Muktieh, CMD, Nedfi. “Most venture capitalists look at commercialisation, but we are also looking at projects that can help the local economy grow.”

While most of the startup activity is limited to Assam and Manipur, other states such as Meghalaya and Sikkim are showing interest as well. Konwar of Startup Assam says, “We have had inquiries from Meghalaya and Sikkim to help them set up an entrepreneur development cell. So people are recognising the effort we are making.”

First Published: Jul 12, 2019, 09:40

Subscribe Now