Second innings: Why SG is looking beyond cricket

India's premier sports goods manufacturing company is looking to cash in on the country's love for fitness

Paras Anand, a third-generation scion, heads sales and marketing

Paras Anand, a third-generation scion, heads sales and marketing

Image: Amit Verma[br]The airstrip on the tree-rimmed Gagol Road in Meerut’s Partapur cuts a forlorn sight. With the government looking to transform the Jewar airport in Noida into western Uttar Pradesh’s premier international aviation hub, the Dr Bhimrao Ambedkar airstrip on the southern fringes of the city bears tell-tale signs of a foiled take off. But right across the two-lane road from its entrance is a three-storied building, with a brick-red and chrome facade, that could perhaps more than make up for an airport lost, by giving wings to sporting ambitions and putting Meerut on the international map.

Consider that the bats that deliver the Hardik-copter—the helicopter shots played by Mumbai Indians’ Hardik Pandya—the ones with which Rishabh Pant tonks his one-handed sixes, or the ball with which Anil Kumble achieved his record-breaking feat of 10 wickets in a Test innings against Pakistan in Delhi in 1999, all originated somewhere in the building. The company, Sanspareils Greenlands (Sanspareils is French for ‘without parallel’), known as SG to most cricket lovers, is one among the three in the world that manufactures balls with which international cricket is played (England’s Dukes and Australia’s Kookaburra being the others) and that are used for Test matches in India. Its fondness for the game is embodied in the statue of a left-handed batsman on its front lawns crunching a drive off his front foot, and its conference rooms named after hallowed cricketing portals—the Eden Gardens, Lord’s, etc.

Behind the office is the factory, which, even on a hot April afternoon, is buzzing with activity: Woodchips and sawdust are flying as bats are being chiselled nimble hands are stitching up pieces of leather before passing them on to be stuffed with cork and rubber cores imported from Portugal and rows of craftsmen move in synchrony as the final seams are put—white on red balls and green on the white ones for day-night cricket. With the recently-concluded Indian Premier League (IPL) and the upcoming cricket World Cup, glut for the game trumps even the high-octane Lok Sabha elections and SG, one of the world’s leading cricket equipment manufacturers, is working overtime to keep up.

Paras Anand, marketing and sales director and the third-generation scion of the family, says, “The demand has shot up. Even as we talk, we are struggling to meet the demand for red balls in the domestic market.”

With a high consumption rate, the sports goods manufacturing industry in India, at the moment, is a good place to be. It is estimated to have gone from $394 million in 2014-15 to $550 million in 2017-18. Jaideep Ghosh, partner and head, transport, leisure and sports, KPMG India, says, “The sports wellness and fitness business in India is expected to grow at 17 percent CAGR by 2022, driven by the Khelo India initiative [a national programme for sports development], entry of international players due to flexible FDI and increase in number of sporting leagues.”But SG’s R&D department has recently been given an additional workout after Indian captain Virat Kohli and spin spearhead Ravichandran Ashwin complained about the quality of their Test balls, lobbying for the Dukes or the Kookaburra to be used in the long-format matches in India. “To have a ball scuffed up in five overs is something that we haven’t seen before. The quality of the ball used to be quite high before and I don’t understand the reason why it has gone down,” Kohli mentioned in a press conference during the home series against West Indies last October. If the Board of Control for Cricket in India (BCCI) pays heed to the complaints of Kohli & Co, SG will have to let go of its biggest brand equity.

But Anand, an avid tennis player who joined the company in 2001, isn’t losing sleep over the threat and calls it a “feedback issue”. “We took it as feedback that the seam needs to be more pronounced. We don’t have a problem in making the core harder. Since Virat made the statement, we have improvised. Now, Ranji Trophy games have been played with the new ball and the players are happy,” says the 43-year-old.

The improved Test ball has received a vote of confidence from Paras Mhambrey, a former Test cricketer and now the bowling coach for the India U-19 and junior teams. “Earlier, the ball would go soft pretty early. But we’ve used the new balls in the A series and the U-19 series and they don’t have any of the earlier issues,” says Mhambrey. With the next home Test series in October, SG’s new cherry is waiting to be tested on the international stage.

THE GAVASKAR EFFECT

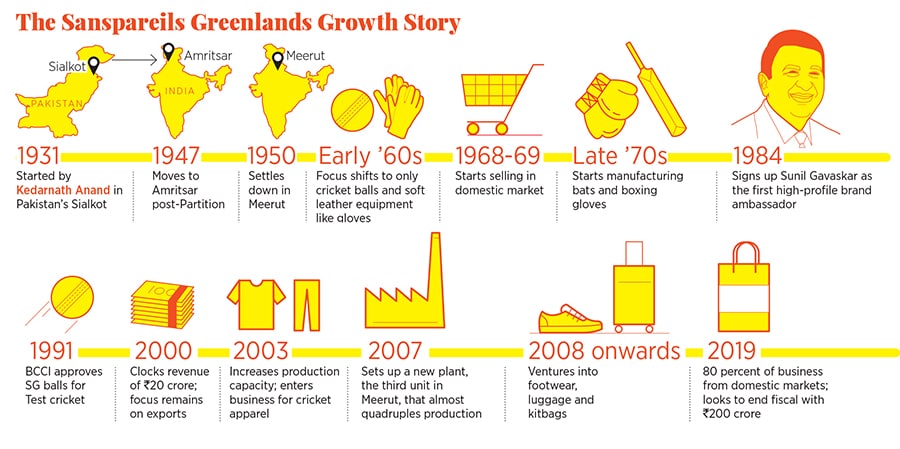

Set up in 1931 in Pakistan’s Sialkot by Paras’s grandfather Kedarnath Anand, SG was a premier exporter of all sorts of sporting equipment—tennis, football, hockey. The family moved to India after Partition in 1947, and took another three years and subsidised land from the government to set up in Meerut in 1950. But Sialkot still dominated in hockey, football and racket sports, so Kedarnath decided to focus only on cricket balls. In the 1960s, SG was exporting balls and soft leather equipment, likes gloves and pads, to key accounts in the UK.

In the late ’60s, the company decided to test the domestic markets by supplying to a few distributors. It worked well and along with orders pouring in from Australia, New Zealand and the UK, “we became the largest players for the categories we were serving in cricket”, says Anand. It gave them the impetus to venture into cricket bats and boxing gloves in the late ’70s.

But the marketing needle began to move briskly in 1982 as SG signed up Sunil Gavaskar to endorse its gloves and pads and, in 1984, its entire range. “He was the tallest batsman in Indian cricket at that time and brought us visibility like never before,” says Anand, narrating how Gavaskar raised the SG bat in 1987 after being the first cricketer to score 10,000 runs in Tests. As demand surged, SG moved from a manufacturing facility of 10,000 sq ft to 50,000 sq ft to ramp up capacity, and became the market leader in the late ’80s. That its acronym matched with the Little Master’s initials was a happy coincidence.

Gavaskar’s association went beyond just endorsement: The opener would visit the factory in Meerut once a year and customise equipment. “In his prime, Gavaskar was rather concerned about the West Indian pacers and their balls fracturing his fingers, so he designed gloves with two joined fingers and extra protection. They looked funny and we were sceptical. But as he played with them, the demand rose and they sold out,” says Anand.

After Gavaskar’s retirement in 1987, SG roped in a raft of top batsmen. Former India captain Mohammed Azharuddin who, for instance, liked SG for producing some of the lightest bats, Rahul Dravid who preferred “not a big edge but a bit of extra wood at the back” and Virender Sehwag who “couldn’t care less about the look and feel as long as the bat had enough punch”.

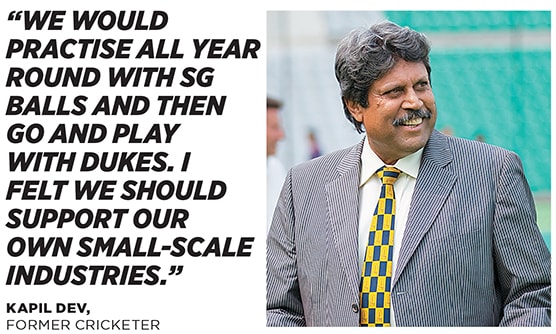

Meanwhile, in 1990, SG started extensive R&D with its cricket balls, pre-testing them with international players, Kapil Dev being among them. Dev is known to have put in a good word for the company, says Anand, following which the BCCI, in 1991, approved SG balls as the ones to play international Test cricket with on home soil. “At that time, we would practise all year round with SG balls and then go and play with Dukes. I felt we should support our own small-scale industries. The problem with SG balls back then was that they had too much glaze on them, not leaving much scope for shining them. The more you shine the leather, the better it becomes. I tried to explain that to SG and through their R&D, they improved tremendously,” says Dev, India’s first World Cup winning cricket captain.

With key cricketers helping in making SG a household name through the ’80s and the ’90s, the company clocked a turnover of ₹20 crore in 2000, of which about 80 percent came from exports. But the domestic market had a vast, untapped potential. In 2007, SG set up its third facility, spanning almost 300,000 sq ft, in Meerut to give it a push and help it quadruple production from about 400 bats a day to 1,500.The expansion, along with the launch of IPL in 2008, and addition of new categories like apparel in 2013, footwear and luggage in 2014 helped in the quick build-up of domestic market and a 10-fold revenue growth. SG expects to close the current fiscal with ₹200 crore of which 80 percent of the business is domestic. “Our focus for the future is growing the domestic business. From being a pure cricket brand, we want to migrate to other categories,” says Anand. He adds that 30 percent of the business comes from bats, 10 percent from balls, another 30 from its protective gear and the rest from apparel, footwear, luggage and accessories combined.

INDIA’S FITNESS DRIVE

It’s the last category that Anand is banking on to propel expansion over the next decade. “Imagine a family of five where no one plays cricket. How do we make an entry there? Through those who might want to do yoga, or go to a gym, or run. India has woken up to getting fit and we want to reach out to them through our non-core categories. In the next 5-7 years, we see them giving us more revenues than our core categories,” says Anand.

According to a Euromonitor research, India’s sportswear market has grown more than 50 percent, from ₹24,000 crore in 2014 to ₹37,000 crore in 2016. The same study predicts an 11.3 percent CAGR growth for the 2016-2021 period. But the market is dominated by the Big Four of Adidas, Puma, Reebok and Nike, and multiple other players looking to make a foray.

Anand is clear that he isn’t competing with the giants of the game. “We aren’t in the battle for premiumisation now. We don’t have that kind of promotional or R&D budget. For footwear, for instance, we want to be at the entry and the medium level, from ₹500 to ₹1,500 and ₹1,500 to ₹2,500 respectively, as opposed to the high-end segment that sells for ₹5,000 and over,” he says, adding that they sold 135,000 pairs of shoes in FY19, up from 70,000 pairs in the previous fiscal.

Cricket, as a core category, too, would need to be relooked at as the game evolves at a breakneck speed. Even 10 year ago, bats would be bought and knocked around for a couple of weeks before being taken to matches. With youngsters now having greater exposure to the game and match practice, there’s hardly any time to prepare the equipment. “We’ve had to increase quality check points and add features, like better flex to bat handles, to ensure our bats are match-ready,” says Anand, who spent the first three years of his tenure on the bat production floor.

Besides, once the BCCI agrees to host day-night Test matches, as most other Test-playing nations, SG will also have to produce Test-quality pink balls for better visibility, like both Kookaburra and Dukes.

Anand says that SG is already producing international-standard white and pink balls. “The challenge here is not of going and selling ourselves, but of supplying in keeping with the demand. Last year, we made 75 dozens of cricket balls a day. Now, we are already up to 115. In the next 12 months, we want to reach 250 dozens. The speed with which we are growing is a lot faster than what we have done in the last 80 years,” he says.

First Published: May 30, 2019, 07:22

Subscribe Now