JSW Sports: Nurturing sporting dreams

Inside Parth Jindal's multi-faceted plan to make JSW Sports India's first listed sports entity

Parth Jindal, the MD of JSW Cement, is banking on sports to give the company a better brand equity

Parth Jindal, the MD of JSW Cement, is banking on sports to give the company a better brand equity

Image: Aditi Tailang[br] It’s only been a few hours since Delhi Capitals’ semi-final defeat and Parth Jindal is rueing the missed opportunity. He narrates in detail how the team couldn’t take advantage of its chances despite a 16-run over that helped them post a respectable 147 against Chennai Super Kings. Still, in the first season since JSW Sports picked up a 50 percent stake in the franchise, its performance has improved dramatically and it stood third in the 2019 edition of the Indian Premier League (IPL).

As Jindal narrates the story, it’s clear he’s what one would refer to as a ‘proper fan’. During his college days, he spent time travelling with his favourite football team, Arsenal, across the UK. Now he’s doing the same with the kabaddi and football teams he owns and the cricket team he co-owns. And like Reliance Industries (the owners of Network18 that publishes Forbes India) and Hero MotoCorp, among two other big corporate backers of sports and sportspersons, he’s also well aware of the business opportunities. Jindal has a clear vision: To make JSW Sports a viable business that is listed by 2025.

Jindal entered the sports business in 2012 when he was trying to figure out how to make JSW a recognisable household brand. He had just graduated from Brown University and one of the first projects he did was to look at the way steel was retailed. Much to his dismay he found that Tata Steel’s Tiscon brand was able to charge 10 percent extra only because the company was better known. JSW’s Neosteel, which according to Jindal is a better product, struggled to gain acceptance in the marketplace.

“This was worrying and baffling for the company,” he says. Jindal decided to look at sports to help the brand resonate better with customers. “I thought if we could do something for non-cricket sports, then JSW could build its brand around that.” The then 23-year-old asked the board for ₹50 crore over the next three years. He’d done his homework and spent time with tennis player-turned-sports entrepreneur Mahesh Bhupathi to understand what India’s Olympic athletes lack—coaches, infrastructure and nutritional support. Mustafa Ghouse, a former Davis Cup player, came in as CEO of a new entity called JSW Sports and they went about building an Olympic sports training academy—the Inspire Institute of Sport—located at JSW’s Vijayanagar steel plant in Karnataka.

Spread over 42 acres, it houses 300 athletes focusing on boxing, wrestling, judo, athletics and swimming and has been built at a cost of ₹90 crore. The institute has an impressive list of medal winners at the Commonwealth Games but the icing on the cake was Sakshi Malik’s bronze at the Rio Olympics that helped it in getting the tag of an official Indian Olympic training institute.

With this success, Jindal, 29, who reckons the country needs at least 20 corporates to support sports, has gone about collecting donations from India Inc to fund the ₹15 crore in annual operating costs. Donors Kotak Mahindra, Marico, IndusInd, Credit Suisse, among others, contribute ₹13 crore annually.

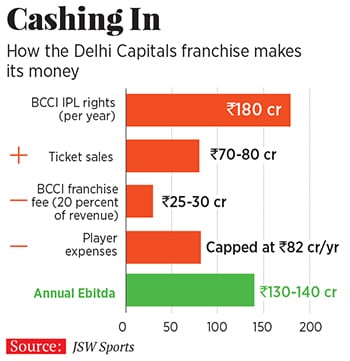

With the institute up and running, JSW Sports went about acquiring teams in the football, kabaddi and cricket leagues. “What excites me is that with most viewing moving to on-demand, sports and news are the two last areas where advertisers have a captive live audience,” says Jindal. It’s also the reason why Rupert Murdoch divested 20th Century Fox, his movie business, to Disney but has held on to his Newscorp.Jindal talks about how cricket franchises in the country have built profitable outfits. Here’s the breakdown. The recent auction of IPL rights closed at ₹16,000 crore. Subtract 10 percent for production costs and the rest (₹14,400 crore) is split between the eight franchises and the Board of Control for Cricket in India (BCCI). That brings in about ₹900 crore per team over five years with 90 percent of this amount being fixed and the last 10 percent based on their league standing. Add ₹70-80 crore from ticket and sponsorship sales. Out of the total revenue, BCCI takes 20 percent as franchise fee after which the teams are left with approximately ₹220 in revenues.

On the expense side, there is a cap on player salaries of ₹82 crore a year, which results in an Ebitda of about ₹120-140 crore per team. For franchises that are debt-free, that is also the annual profit.

One additional payout the teams get is based on their league standing with ₹39 crore for the top placed team and ₹5 crore less for every subsequent spot. A total of 17.6 million viewers streamed the IPL on their phones and TVs in 2019 and Jindal expects the next round of IPL rights to be auctioned for far higher than ₹16,000 crore.

The story is repeated in kabaddi, albeit with much smaller numbers. JSW Sports acquired the Haryana Steelers in 2017 and Jindal makes it a point to attend all their home games in Sonipat, Haryana. The total cost of operations is about ₹15 crore and while larger teams manage to break even, for smaller teams like the Haryana Steelers there is a ₹1-3 crore deficit. Jindal expects TV and digital rights (kabbadi viewing is about 15-18 percent of IPL) that bring in ₹6 crore in revenue to be renegotiated and that should help make all teams profitable. In their first year as a JSW Sports co-owned team, Delhi Capitals finished a creditable third

In their first year as a JSW Sports co-owned team, Delhi Capitals finished a creditable third

Image: Gokul VS / Hindustan Times via Getty Image[br]The first franchise that JSW Sports started with in 2013 was football team Bengaluru FC it is also yet to turn a profit. Jindal acknowledges that the path to profitability in football is at least five years away. Cost of operations, which includes franchise fee, player fees, travel, stadium operations and running academies, is ₹50 crore, with revenues in the form of TV rights, ticket sales and sponsorships at ₹25 crore. Jindal has pinned his hopes on higher revenues coming in from TV rights to make the club profitable as well as Indian players doing better globally. “All we need is one Indian to play in a European club and we will see football’s popularity explode,” he says. Bengaluru FC is in talks with a European club for a long-term tie-up.

As he continues to build JSW Sports, Jindal envisages four distinct revenue streams. First, the franchises that the company owns. Second, the sports management business where JSW Sports manages athletes. They represent 37 sportspersons, many of whom have trained at Inspire Institute of Sports. Third is a bespoke sporting experience business. As Indians get wealthier, travelling for sporting events is beginning to catch on. A one-month trip for the Champions League is a logistical nightmare. From match tickets to accommodation and travel to visas, JSW Sports will put together a custom-made plan. Jindal hopes to offer this service to individuals as well as corporates.

Last, Jindal also plans to build stadiums across the country. “Today, all stadiums are government-owned and there is no incentive for them to maximise the potential of their assets,” he says. Besides, the fact that governments own most of the prime land in the heart of cities means that Jindal will be pitching the idea of privately-owned commercially-operated stadiums to them. JSW Sports would build and rent the stadium out for matches, marriages and concerts. He says there is a lot of interest from private equity capital for this business.

“In order to sustain a sports business, it is very important to have investments in infrastructure and that is where JSW scores over other corporates in India,” says Rudradeep Banerjee, partner at Second Innings Sports and Entertainment, a sports management agency.

For now, JSW Sports is content with its three franchise teams and doesn’t plan to bid for sports like volleyball or badminton. Jindal also scores well on his original aim—to get better recognition for the JSW brand. He cites research done by Brand Finance that placed the JSW brand at 53 in 2014 and at 41 in 2018. Tata Steel’s Tiscon is now priced only 1 percent higher than JSW’s Neosteel.

Last stop: An IPO circa 2024-25 making this India’s first sports company to be listed. He’s expecting the market to value it like any consumer business with high multiples as sports franchise rights are perpetual. “Not as high as Asian Paints but somewhere between that and the steel business would be a good multiple,” he grins.

First Published: May 29, 2019, 10:41

Subscribe Now