Would you want a computer to judge your risk of HIV?

Scientists say it is possible to correctly identify men at high risk by examining their existing medical records, raising ethical questions about how doctors should use this tool

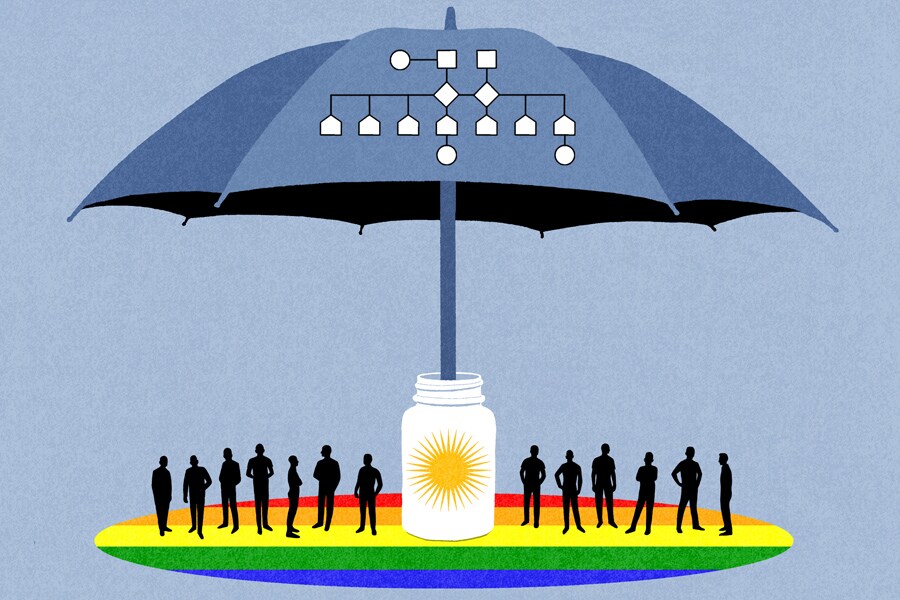

No electronic distribution, Web posting or street sales before Tuesday 2:31 a.m. ET July 30, 2019. No exceptions for any reasons. EMBARGO set by source.** Scientists have developed an algorithm that estimates which patients are most likely to become infected with the HIV virus and should be taking a daily pill to prevent infection, known as PrEP. (James Steinberg/The New York Times)[br]A few years ago, researchers at Harvard and Kaiser Permanente Northern California had an inspired idea: Perhaps they could use the wealth of personal data in electronic health records to identify patients at high risk of getting infected with HIV.

No electronic distribution, Web posting or street sales before Tuesday 2:31 a.m. ET July 30, 2019. No exceptions for any reasons. EMBARGO set by source.** Scientists have developed an algorithm that estimates which patients are most likely to become infected with the HIV virus and should be taking a daily pill to prevent infection, known as PrEP. (James Steinberg/The New York Times)[br]A few years ago, researchers at Harvard and Kaiser Permanente Northern California had an inspired idea: Perhaps they could use the wealth of personal data in electronic health records to identify patients at high risk of getting infected with HIV.

Doctors could use an algorithm to pinpoint these patients and then steer them to a daily pill to prevent infection, a strategy known as PrEP.

Now the scientists have succeeded. Their results, they say, show that it is possible to correctly identify men at high risk by examining medical data already stored about them.

But the researchers know they must tread delicately in using the software they developed. It’s one thing to have a computer find a patient who is at risk for breast cancer. But to have software that suggests a patient is a person who too frequently has unsafe sex and risks HIV infection — how should doctors use such a tool?

And if they do, can they initiate a conversation about a patient’s sexual health with understanding and delicacy?

“This certainly could be an aid for providers,” said Damon L. Jacobs, a marriage and family counselor in New York who takes PrEP and educates others about it.

But a lot depends a lot on the doctor: A calculator that says a patient is at risk “doesn’t mitigate the fact that providers are often uncomfortable and clumsy talking about sex,” he said.

And patients — especially those in minority communities who may mistrust doctors — may well bristle. “Who’s looking over my records? You think I’m a slut? You want me to take an ‘anti-slut’ pill?” said Jacobs, musing about how patients might react.

Clearly, doctors should not spring such a result on patients, said Dr. Ellen Wright Clayton, a professor of health policy at Vanderbilt University. Instead, she said, they should ask patients first if they want their records reviewed by the software.

The drug Truvada, made by Gilead, was approved seven years ago for PrEP. Taken daily, it appears to be almost completely effective in protecting users against HIV infection.

But just 35% of the 1.1 million people who could benefit from the pills use them. And there are nearly 40,000 new HIV infections a year in the United States.

The problem is especially acute among black gay and bisexual men: 1 in 2 will be infected with HIV in his lifetime, said Dr. Julia Marcus of Kaiser Permanente and a developer of the new algorithm.

Use of PrEP has lagged for a number of reasons. Until recently, insurers did not always pay for the pills, which have a list price of about $2,100 a month. And patients do not always have a regular doctor who knows them well enough to discuss HIV risk.

For the most part, the onus has been on patients to ask for PrEP, said Dr. Douglas Krakower, leader of the Harvard group developing an algorithm. “Clinicians are very busy and have limited time and tools to identify people who may be at risk,” he said.

Software might spare them the effort. “We intuitively felt like there were many data elements in the electronic health record that could predict risk,” Marcus said. The challenge was to identify which ones worked best.

So the groups developed several models, using electronic records from 3.7 million uninfected patients at Kaiser Permanente and 1.1 million patients at two Massachusetts medical centers.

Some models were simple: The software looked at little more than sexual orientation and history of sexually transmitted diseases. But others were more complex.

The scientists tested these models by using them to review health records of people who were free of HIV infections and asking if they could identify who subsequently became infected.

The final Kaiser Permanente model included 44 predictors and factors like living in an area with a high incidence of HIV, use of medications for erectile dysfunction, number of positive tests for urethral gonorrhea, and a positive urine test for methadone.

The software flagged 2.2% of the patient group, correctly identifying nearly half of the men who later became infected. The Harvard group had similar results with its model.

Marcus said that there is a real need to identify patients at risk. Half the patients at Kaiser Permanente Northern California who became infected said they had not known about PrEP.

“Sexual health discussions may be awkward, but they’re standard of care,” she said.

She added that the group also will be asking patients and providers about their experience with the algorithm “to make sure we implement our prediction tools in the most practical and sensitive way.”

But the algorithm did not identify everyone at risk, Clayton noted. So, after asking patients if they want the screening, doctors will have to explain that the test is not perfect and ask: “Are there other things in your life that make you more at risk?”

Chris Tipton-King, a San Francisco filmmaker who takes PrEP, said the risk calculator could be a good opening for a dialogue between a doctor and a patient.

“There are two sides to this equation,” Tipton-King said. “One is educating patients, the other is educating doctors.”

A good friend of Tipton-King recently asked his doctor to prescribe PrEP. According to Tipton-King, the doctor replied: “Why don’t you just stop having so much sex?”

Two weeks later, he said, his friend tested positive for HIV.

First Published: Jul 30, 2019, 14:22

Subscribe Now