Facebook - Too Much Hype, Too Little Substance?

India is going to be the biggest market for the social networking site, but the company is yet to convert its advantage into money

Ever since its initial public offering, Facebook has been slammed as a prime example of a company whose economic reality couldn’t live up to the hype surrounding it. Its record in India might turn out to be no different.

When Facebook’s share price started tumbling down since its listing two weeks ago, not everyone was surprised. In February, as soon as its numbers became public, Aswath Damodaran, a finance professor at NYU Stern School of Business, valued the company at $72 billion. It made a debut with a valuation of $100 billion, or 100 times its earnings. Apple’s, by way of comparison, is about 14 times its earnings. Many analysts expected the price to drop, and it did.However, even this realistic and reduced price does not take away the achievement of Facebook on the internet in general, and its dominance in social media. But the question is whether there is too much hype surrounding Facebook, relative to its revenue-earning potential. Its current market price implies revenue of $44-45 billion in 10 years. (It’s about $4 billion now).

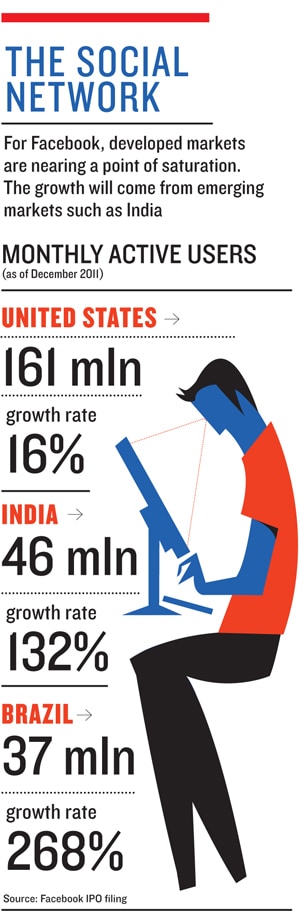

Where does India stand? With its Western markets nearing a point of saturation, Facebook counts India among its important markets. Its IPO document mentions India three to four times. In terms of users, India, along with Brazil, was a key source of growth for Facebook in the last few years. At the end of last year, India had 46 million active users and second only to US, which has about 161 million users, according to Facebook’s IPO filings.

The future looks promising. In terms of population, only China can match the market size. But in China, Facebook is banned, and customers have moved to local versions. In India, the number is likely to grow as internet penetration increases. In the next three years, India’s internet users are estimated to double from about 150 million at present. The time they spend online, which is lower than Brazil and China, is expected to go up too. All these should bode well for Facebook. If it maintains the penetration rate of about 30 odd percent, its user base will touch 100 million in the next three years.

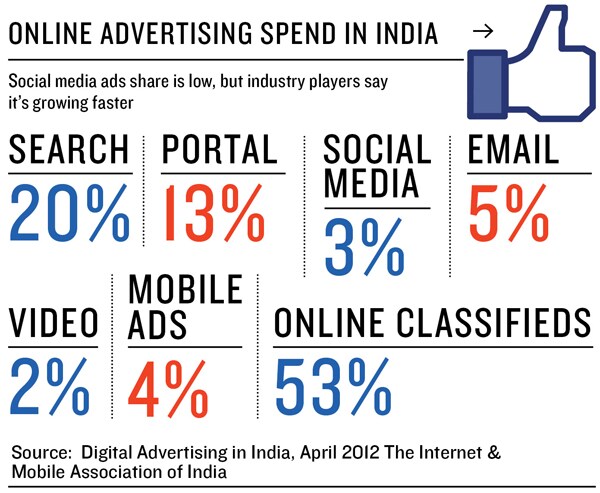

The question, however, is how well it can monetise that user base. The market potential is huge. Adoption of internet, shift from a saving society to a consuming society, all suggest a huge potential for digital advertising, a main source of income for Facebook. Indian businesses spent Rs 2,850 crore on digital advertising as of March 2012, a number that’s expected to grow to Rs 4,391 crore next year, according to a report by the Internet Mobile Association of India/Indian Market Research Bureau (IAMAI/IMRB).

Asfaq Tapia, former manager social media marketing at Zapak, says, “Of the online budget, lately, social media gets 10 to 15 percent. Brand managers hire agencies for social media on a retainership and pay them around a lakh or 1.5 lakh for social media management.” Since Facebook is the dominant social media outlet, most went towards Facebook.

But Facebook has not been able to capture much of this share. Mahesh Murthy reckons that businesses spent about Rs 150 crore on Facebook marketing, but only a third went to Facebook’s own kitties in the form of ad revenues. The rest went to social media marketing firms which handle Facebook accounts. Part of it is because the benefits of Facebook are not necessarily driven by advertisements. Ramakrishna NK, of Rang De, an online microfinance aggregator, says that the company is very active on Facebook, but has spent only negligible amount on ads on the site.

Another reason is Facebook has just started promoting its advertisement services in India, and some say the support from the company is not good. It competes in the same segment as Google, which not only has more services but also better processes in India. At present, Google dominates the digital ad spending in the country. Things might change in favour of Facebook as more ad spends go towards social media.

However, a big concern is whether there is too little substance around Facebook engagements right now. Facebook ‘likes’ are generally seen as an indicator of success of social media marketing, but there are ways to manipulate these numbers. Some social media companies do just that, in a repeat of what happened during the earlier dotcom boom days. Then, companies hired people just to click on ads. While that might have increased page views, they amounted to nothing. Tapia says right now a lot about Facebook is hype. It’s a report card for brand managers who need to show how many followers and fans they have.

Another big trend in India that might not be of much use to Facebook’s revenues is the rise of mobile phones. According to IMRB, there are about 48 million active mobile internet users in India an icube survey showed that 9 percent of users access internet primarily from their mobile phones. This might help Facebook collect better locational data of its users. However, more people accessing Facebook through mobile phones put a constraint on its ad revenue model—both because of space available for ad display and also the typical behaviour of customers while on the mobile phone. The ad conversion rate is lower on mobile phones. And Facebook is yet to have a mobile strategy for ad revenues in place.

Facebook could still find a technological or a business solution for all these issues. Recently, it added an option to promote individual posts for payments ranging from $15 to $30. This expands the scope for revenues beyond traditional advertisements and could work as well in a mobile platform. Moreover, there were rumours that Facebook is looking at acquiring Norway-based Opera, maker of an internet browser popular among mobile phone users especially in emerging markets, and Face.com, an Israeli company that has a face detection technology. Facebook may or may not make these acquisitions, but the rumours and the media coverage highlight the fact that Facebook is operating in a different environment now. The challenge will be to find a balance between investors impatient with slow growth and those concerned about high risks.

First Published: Jun 12, 2012, 06:00

Subscribe Now